At 49, with her two sons in grad school and college, she divorced her husband and moved 3,000 miles from Seattle to that famous New York City bohemian redoubt of the Chelsea Hotel. At last, a room of her own.

Today that might seem a familiar feminist path toward self-realization, but in 1972 the late artist Doris Totten Chase (1923-2008) was an atypical trailblazer from an obscure outpost. And, according to those who knew her, probably not the type to label herself a feminist.

Few women artists were recognized at the time in the Pacific Northwest. Fewer still would dare to gamble on a second life chapter in New York City. And when she permanently resettled in Seattle three decades later in 2004, she was virtually unknown to the next generation of gallery- and museum-goers.

But if you’ve ever taken visitors to the best view in Seattle, you know Chase’s most prominent work: Changing Form, in Kerry Park, on the south prow of Queen Anne Hill. Installed in 1971, that large, rusted-steel sculpture is photographed by countless tourists, wedding parties, and selfie-seekers. Those coming for the iconic views of the Space Needle and Mt. Rainier may wonder who created the two stacked geometric, cut-out blocks, their massive volumes reduced to delicate outlines.

Who indeed. Some answers can be found in her first career retrospective at the Henry Art Gallery, where Doris Totten Chase: Changing Forms continues through October 1. (The show is culled from her two sons’ gift of 59 works and supporting materials to the Henry and U.W.) But the emphasis is on her art — sculpture, painting, and videos — and not her rather remarkable biography. Chase died in 2008 at the age of 85.

Chase first gained a regional reputation as a painter and sculptor during the ’50s and ’60s. A middle-class Roosevelt High School grad, she had studied architecture for two years at the U.W. until her marriage, at age 20, to World War II Naval officer Elmo Chase. Later she studied painting, with teachers including Kenneth Callahan, one of the famous “Big Four” of the Northwest School.

Her life took a catastrophic change in 1950. “I was 27 years old, and I thought my life was over,” she told Patricia Failing in her book Doris Chase, Artist in Motion. The book and a companion video are in the Henry’s study foyer.

“Gary, my first child, was three, and I was pregnant with my second son, Randy. Then my husband Elmo came down with polio and was completely paralyzed. He was in the hospital for six months, and we were broke. Thanks to the Polio Foundation, we didn’t lose the house. A lot of our friends dropped away. I don’t think I could have survived that period without my painting. Sometimes it wasn’t very good, but thank God it was there.”

Second son Randy also says that post-partum depression following Gary’s birth led their mother to painting-as-therapy, after her psychiatrist told her to take up the brush. Then came the classes with Callahan and other teachers.

By 1956, with her husband mostly recovered and working as an accountant, Chase was accomplished enough to earn a solo show at the Otto Seligman Gallery (later run by Francine Seders). Her painting was winning prizes and appearing in New York.

Chase’s early nature scenes, figurative works and a group portrait rendered on thick, bas relief concrete can be seen in a back gallery at the Henry. This is the Northwest School in bloom, with organic, natural forms galore.

“It was a period style she jumped into,” says veteran local critic Matthew Kangas. “Her paintings were hip enough that she was showing in New York.” Indeed, they’re perfect for the walls of a tastefully restored Paul Thiry rambler, and a suitable starting point to the non-chronological Henry show.

Reverse course through two small flanking galleries, and you’ll see Chase’s mid-’60s transition to sculpture. The models and maquettes are sometimes studies for larger projects (Changing Form among them). Irresistibly and tactilely crafted from wood and metal, their vibe is Danish modernism meets Dr. Seuss. (Several are on loan from Chase’s local dealer, Abmeyer + Wood Fine Art.)

Randy Chase explains that, into the early ’70s, Chase created blocks, hoops and sculptural shapes intended to facilitate children’s playground activities. From there, she scaled up her kinetic art for interactive dances with members of the future Pacific Northwest Ballet.

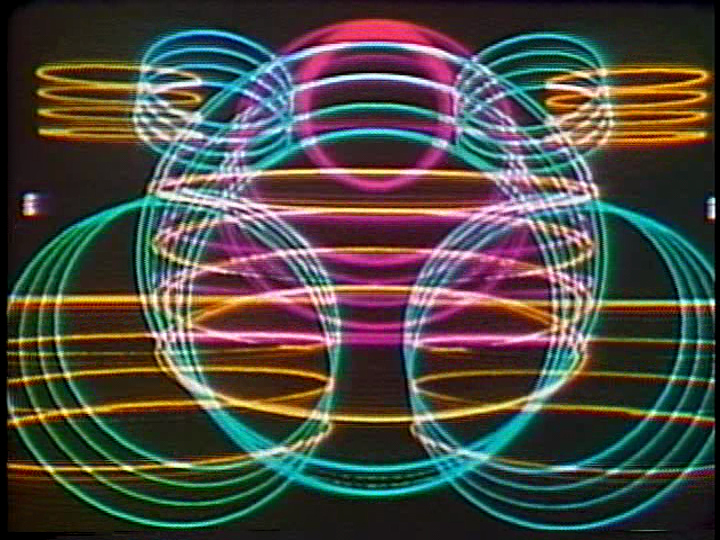

[video still]

. 1970-1971. Image courtesy of Randall J. Chase.

And that brings us to the main gallery, where two-dozen videos can be found on kiosks and projected onto walls. These include a video on Mantra, Chase’s 1969 collaboration with choreographer Mary Staton, and Circles II, her most iconic video work. Also projected large is the prior Circles I, a more abstract computer video made with the assistance of a Boeing mainframe computer and its engineers. It’s primitive by today’s standards, but with a retro, four-bit Atari charm.

Chase had been ready to leave painting and sculpture. “If you look at parallel figures in the Northwest in that period, there are very few who are making those leaps,” says Luis Croquer, who curated the show, his last at the Henry before recently assuming the top job at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University.

“She was incredibly determined,” says Croquer, “someone who’s constantly pushing boundaries and pushing herself, not searching for a signature style.”

Or a signature medium. “She was never bound by what was working at the time,” says son Randy. Painting, and the Northwest School in general, offered few new avenues for a woman of that era. So why not video instead?

Says Croquer, “Doris was never really a part of what you call the arts establishment in Seattle. She wasn’t really a player. She’s carving out this career very much on the periphery.”

Son Randy adds, “Seattle was kind of a boys club. There was definitely sexism, and she was aware of it. She had to fight as hard or harder to get the art out there and be a part of the game.”

Changing that game, and changing cities, was the next act of Chase’s self-reinvention.

“She became Doris Chase in New York, not Seattle,” says Kangas.

At the Chelsea Hotel, she befriended George Kleinsinger, Lee Breuer, Shirley Clarke, Jonas Mekas, Nam Jun Paik and other downtown notables. “I saw that there was another world, and there is a second chance,” she told Failing.

That second chance coincides with the era of An Unmarried Woman, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, and even The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Likewise, Chase’s journey epitomizes a certain optimistic, feminist spirit of the ’70s, the era of the Equal Rights Amendment and women’s lib.

Eventually, health woes and mishaps brought her back full-time and full-circle to Seattle in 2004. “She got hit by a car, and she got mugged,” recalls Randy. Chase spent her final years at Horizon House, continuing to make art until suffering a series of strokes and Alzheimer’s disease.

What sticks with you from the Henry show, and if you read some of the background materials, was how much entrepreneurial zeal Chase brought to managing her career. And this at a time when few women worked as managers or artists. “She was her own PR department,” says Randy. “She worked six and one-half days a week her whole life. She worked her ass off. She was a networker.”

In the study-area videos, the petite Chase comes across as poised, polite, and comfortable on camera. She’s not angry or confrontational; leave that to the following hard-F feminist artists of the ’80s, like Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer or the Guerilla Girls.

“There’s a kind of soft power that I find fascinating,” says Croquer, who lauds her “hustle and ambition.”

Speaking for herself, in the companion videos, Chase talks of her interest in “kinesthetic experience” and “kinetic painting.” Video, unlike painting or sculpture, allowed Chase a freedom of “putting the line down and maybe erasing it and putting the line down again.”

Chase was interested in “breaking down the idea that art had to be a static object,” we hear her saying in one of the videos. The same could be said for static ideas of life, marriage, career, and identity.