This story originally appeared on NWPR/EarthFix.

On Wednesday, as smoke blotted out the sun across the city of Portland, about a dozen people were hiding out from the smoky heat in the air conditioned Hollywood Senior Center — one of the county’s designated cooling centers for those needing relief on the hottest days of the year.

Wearing an electronic air filter around her neck, Jennifer Young, who works at the center, flipped on the larger, high-efficiency particulate filter she brought from home to purify her work-space air.

As soon as smoke from the Eagle Creek fire started flowing into the city from the Columbia River Gorge, Young, who has asthma, felt it in her lungs.

“I’m really short of breath," she said. "I noticed it this morning. I was debating whether or not to come to work.”

So, even inside the cooling center, she was taking extra precautions because the particles in wildfire smoke are irritants that can trigger an asthma attack.

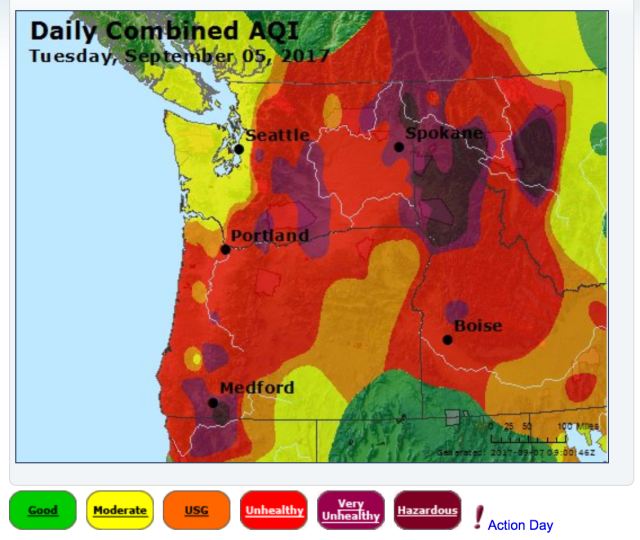

This summer, wildfire smoke has at times blanketed much of the West, with ash falling from the skies. The resulting unhealthy air quality is dangerous for people with lung and heart problems.

Young spent a lot of her childhood summers in the hospital when smoke from nearby field burning would close down her airways. This week, she’s avoided any hospital visits, but she has had to use her inhaler to help her breathe.

“My asthma unfortunately is not well controlled and I have a lot of lung damage because of that,” she said. “Any time the air gets bad I’m going to feel it.”

A big question for people like Young is how much more bad air they can expect in the future with climate change.

Brendon Haggerty, who tracks the health impacts of climate change for Oregon's Multnomah County, said as summers get hotter and drier, research shows fire seasons and the smoke that comes along with them are likely to linger longer.

“Like a lot of people, I look outside and I wonder if every summer is going to be like this, and I think the signs are pointing more and more toward yes — to some extent,” he said. “We can expect to have to deal with this more and more often as the climate continues to change.”

That means more bad air days and more health risks for people with asthma and heart disease.

We’ve already seen an increase in the number of acres burned and the length of the fire season, Haggerty said.

“Since the 1980s it’s more than doubled,” he said. “So we’re now over a three- maybe four-month fire season whereas when my dad was young it was less than a month.”

The latest national climate assessment projects the number of acres burned by wildfires will quadruple in the next 70 years.

“So, this summer feels like a lot, but I can’t imagine what it would be like to have four times as much fire in the Pacific Northwest,” he said.

For people with asthma, it could mean some very unhealthy summers.

Matt Hoffman, who works on air quality issues for Multnomah County, said he knows the feeling of waking up to wildfire smoke all to well.

“I have asthma myself, and on days like this when I wake up I can feel the tightness in my chest,” he said. “We’ve spent months now under the haze of smoky skies, and Portland hasn’t had it that bad.”

Across the Northwest, some communities have faced unhealthy air every day for much of the summer.

It moves beyond that risk of my eyes hurt today or I might be having a hard time breathing today when it becomes a third or a fourth of the year that we have to experience these types of conditions,” he said.

This week, the number of asthma-related hospital visits across the state of Oregon jumped 24 percent, according to the Oregon Health Authority. Haggerty says in the future, people may have to find ways to clear smoke-filled air.

“The good news is we’ll get better at that,” he said. “We’ll get better indoor air filtration. We’ll get better air conditioning systems. We’ll plant trees in ways that protect us. But when I look outside I worry about what it will be like in the future.”

He hopes the ash falling from the sky might lead more people to consider driving less and cutting back their personal contributions to climate change.