Even without the extended wait for clear results in the mayor’s race, this primary election was a grueling one. With 36 candidates spread among only three municipal races, voters were faced with an incredible number of choices — many genuinely viable. But the complexity also makes the race an incredible opportunity to learn more about the nuances of our city and its voter base.

Now, there’s reason to resist over-analyzing in election analysis. Elections do not always reveal irreversible trends in electoral sentiment, or paint some definitive picture of How We Are Now. However, a close read of the returns can tell us a lot about our political moment and individual candidates’ stories. And with 21 candidates in the mayor’s race alone, there are a heck of a lot of stories to tell this year. Let’s look at three of the big takeaways from a detailed, precinct-level analysis of Tuesday’s results.

First, a caveat: The results below are based on the precinct results from primary night. In this Seattle election, as in most of the past, ballots counted two or more days after Election Day skewed much more toward lefty candidates (Hat tip to civic organizer Michael Maddux for pointing out that the trend doesn’t start the day after the voting deadine, as is often said). Jenny Durkan, for instance, polled 31.6 percent on Election Night and has since declined to just under 28 percent; in contrast, Cary Moon and Nikkita Oliver have risen. To avoid confusion, I will not attempt to make adjustments, but hardcore numbers nerds can dive into the final results on Aug. 16.

Durkan: No free ride

The consensus seems to be that Jenny Durkan’s primary showing positions her somewhere between a frontrunner and a juggernaut. “Frontrunner” is probably a fair label, but the results indicate reason to be a little bearish. While Durkan’s campaign is well-funded and has wide support from elected officials, she may have a significantly tougher time picking up votes than Cary Moon, the presumed second-place finisher who will advance to the Nov. 7 general election with Durkan.

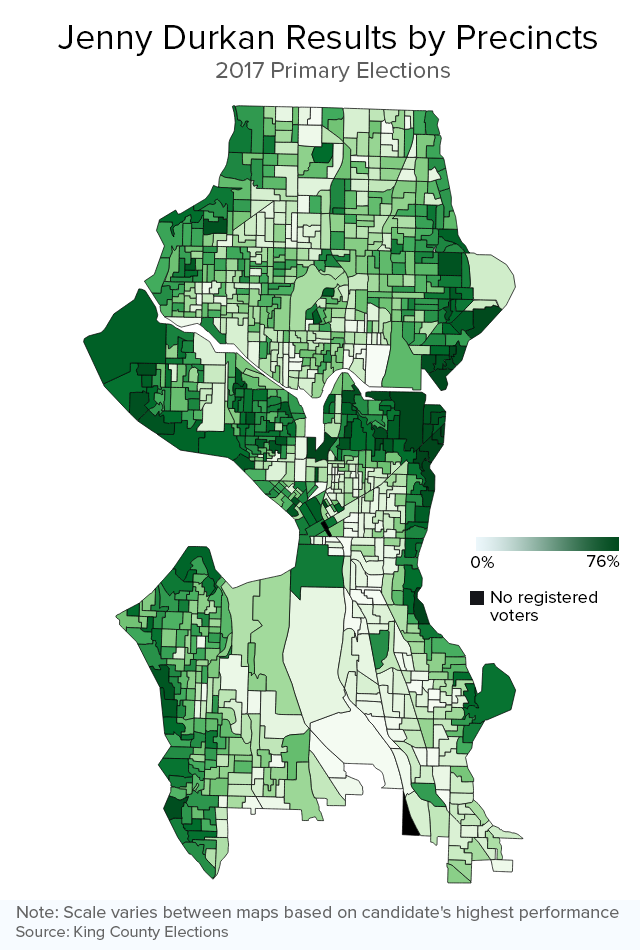

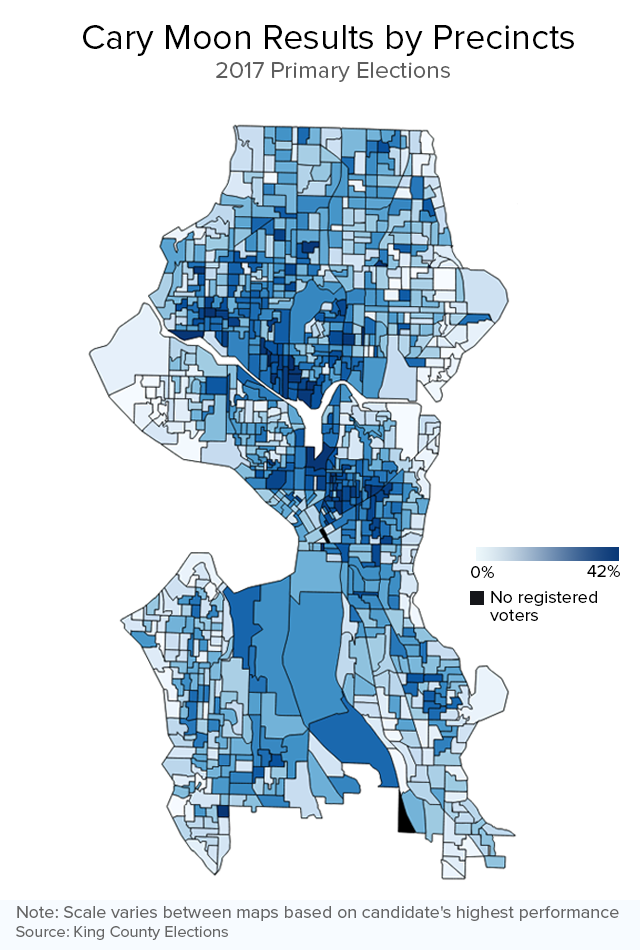

To understand why, let’s look at which “lanes” each candidate runs in. Durkan very clearly runs in the center lane of Seattle politics. If she wins, it will be with a base similar to those of Mayor Ed Murray, Councilmember Tim Burgess, and former Councilmember Richard Conlin: older, higher-income, and more likely to own their own and live in single-family residences. This is evident from Durkan’s top-performing neighborhoods: Broadmoor, Washington Park and Madison Park — Seattle’s three most affluent. Cary Moon isn’t as ideologically pure of a lefty candidate as some, but opposing Durkan virtually guarantees she will occupy Seattle’s left lane electorally. Indeed, she already does, to some extent; her top neighborhoods were lefty strongholds like Fremont, Capitol Hill and Georgetown.

Durkan did better in her top neighborhoods than Cary Moon did in hers. Durkan, after all, shared the primary’s center lane with only minor candidates. Moon, on the other hand, heavily split the left lane, especially with the apparent third-place finisher Nikkita Oliver. But what’s notable is how little head room Durkan has for improving in her strongest neighborhoods come November. In the primary, she received 65 percent in Broadmoor, 64 percent in Washington Park, and 57 percent in Madison Park. With those 21 candidates on the ballot, that’s impressive. It’s also bad news for the leader: It means Durkan won an impressive share of her “gimme” general election voters in the primary. Cary Moon, by contrast, maxed out at only 28 percent in her top neighborhood (Fremont).

Looking more closely at the precinct-level results suggests another way the battle may be tougher than expected for Durkan. Three eliminated candidates’ votes (business-sector conservatives Gary Brose, Larry Oberto and Lewis Jones) are likely to overwhelmingly flow to Durkan, but they received only 4 percent combined. Durkan will also likely pick up a healthy amount of Jessyn Farrell’s support in Northeast Seattle-based 46th Legislative District, which Farrell represented in the state House of Representatives. Elsewhere, however, the results indicate Durkan will likely struggle to pick up supporters of eliminated candidates. Votes for Bob Hasegawa, Mike McGinn and minor candidates were mostly in areas where both Durkan and past center-laners fared poorly.

Durkan’s campaign, which took a decidedly progressive tone in the primary, was likely hoping for a breakout performance. She didn’t get one. While Durkan is certainly well-positioned, she will need to expand her base beyond the centrist core in November, when higher turnout broadens the electorate.

Moon v. Oliver: The left, divided

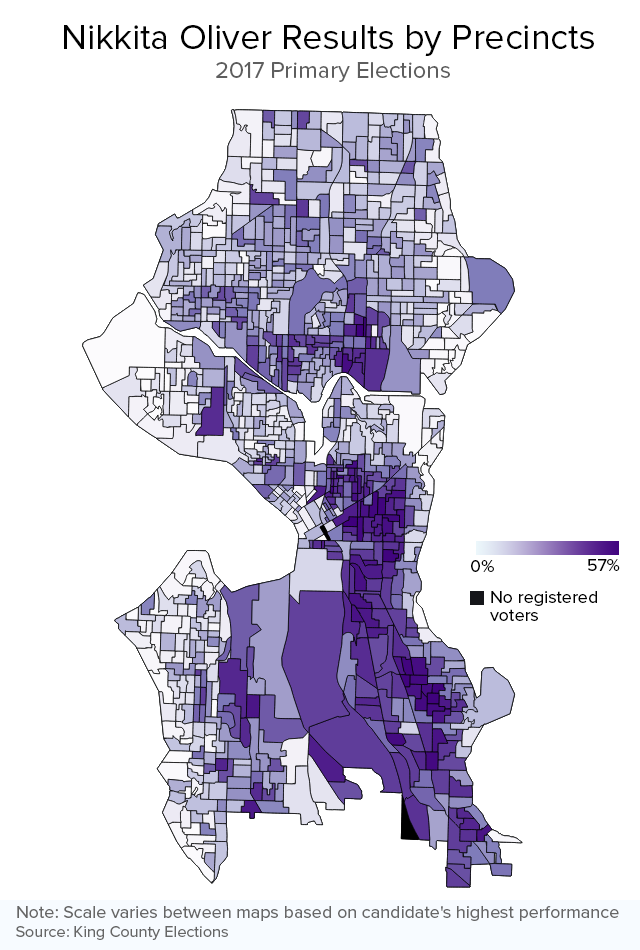

We now move over to the left lane, where it appears that urban planner and Stranger endorsee Cary Moon has edged out activist Nikita Oliver, barring any recount and unlikely reversal. Both candidates competed for a similar base of younger, lower-income and more diverse voters. However, the precinct results show that the “left lane” splintered in fascinating, telling ways.

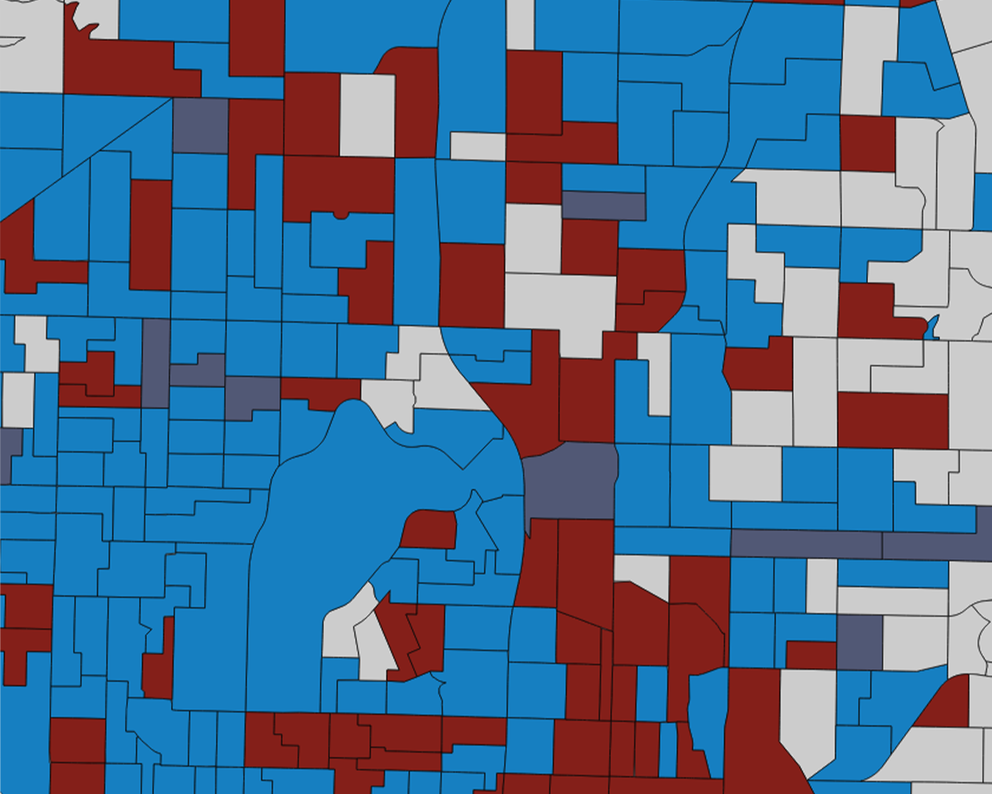

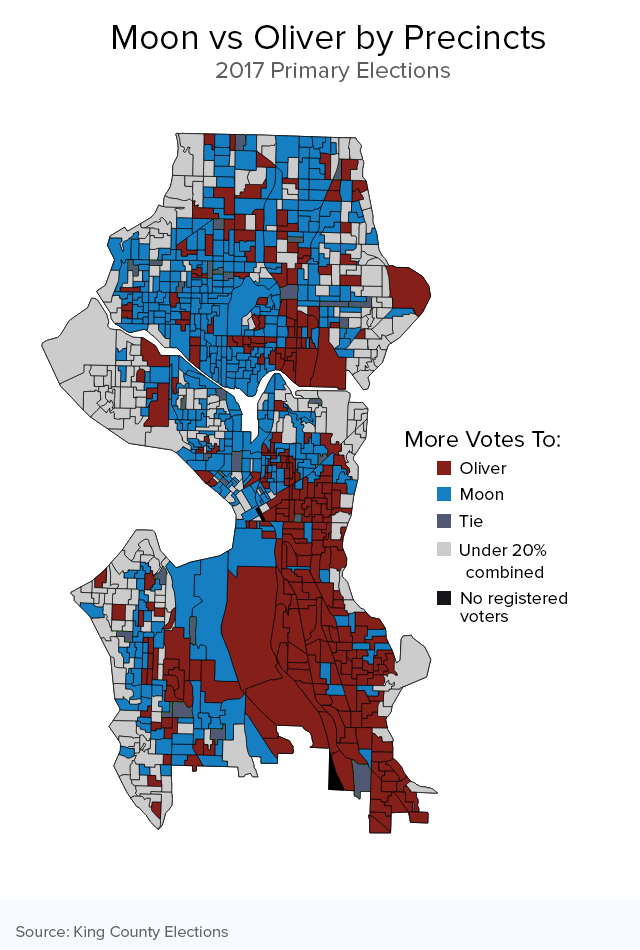

The map below focuses on precincts where Moon and Oliver won at least 20 percent combined, and indicates who came out on top. Not every neighborhood saw either candidate register a substantial share of the vote. For instance, in Seattle’s two country club precincts (Broadmoor and Sand Point), the two combined to only 3 percent, with Oliver placing 8th and Moon, 12th. In left-leaning, renter-dominated areas where they were forces, though, Oliver won more diverse and working-class precincts, while Moon clearly excelled in whiter areas and with white-collar workers.

Looking at only the two candidates, Oliver’s best performances included Columbia City (67 percent), Rainier Beach (65 percent), Beacon Hill (65 percent), and the University District (57 percent). Oliver also edged Moon in Capitol Hill’s Broadway neighborhood, despite The Stranger’s historical strength there. In these areas, Oliver did well even in heavily white precincts. The division seems to be about ideological focus as much as demographics. Moon’s best two-way showings include Downtown (71 percent), Denny Triangle (67 percent), Westlake (65 percent), and Ballard (64 percent). These tend to be areas where even the left-leaning base is higher-income, and more populist-oriented candidates like Oliver sometimes underperform.

Despite occupying the same lane, Moon and Oliver’s performances were strongly linked. Either would have made it through the primary in a walk on their own. But this shows that Seattle’s “left lane” voters – who have unified around candidates as polarizing as Kshama Sawant – are divided in ways not dissimilar to the national splits among progressives. Indeed, with the exception of Oliver’s higher performance among minority groups, the Moon/Oliver split bears surprising resemblance to the Clinton/Sanders split of the 2016 primaries.

Turnout: Some things (almost) never change

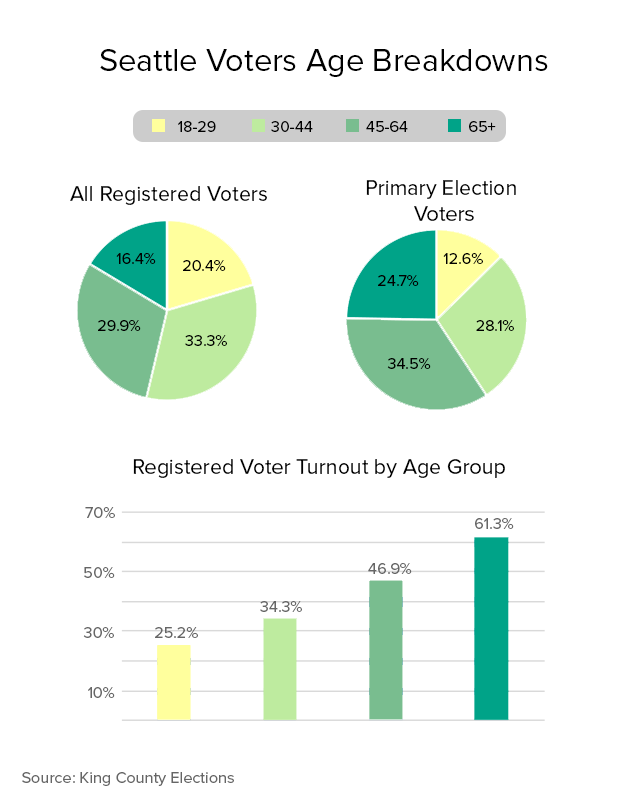

Arguably, the candidacy of Nikkita Oliver has been as compelling an electoral story as any this year. Oliver, a political unknown, created a viable political movement and raised well over $100,000. But, while Oliver’s candidacy was impressive, it also shows the structural problems facing left-lane candidates – especially “movement” ones – in primary elections.

One of the most common questions I get from candidates in my role as a political consultant goes like this: How important should turning out infrequent voters be to my campaign? This often feels like an attractive option to left-leaning candidates, whose base is more likely to skip primaries or even general elections in non-presidential years. But, especially in the primary, my view is that this is a very difficult, resource-intensive task. Research shows that turning out infrequent voters is difficult, requiring either repeated campaign contact or social pressure. While campaigns like Oliver’s can certainly turn out hundreds of infrequent voters or more, those are often just a drop in the bucket. The total vote count in Seattle’s primary this year is approaching 190,000.

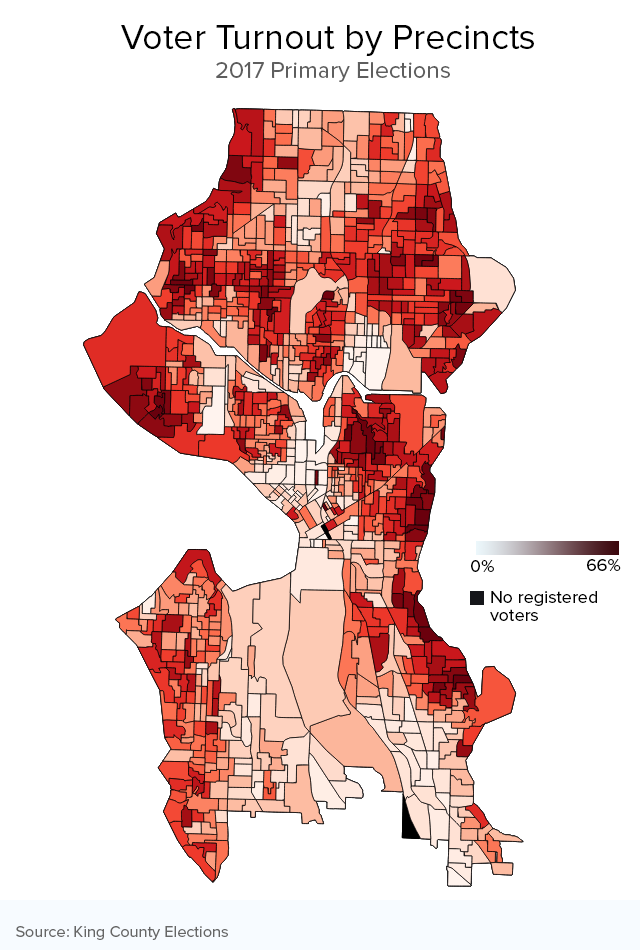

Indeed, my analysis indicates that while Oliver and other left-laners may have turned out some infrequent voters, they were overwhelmed by larger electoral trends. It’s true that Seattle’s primary turnout was unusually strong — over 40 percent, a recent record for a primary in this type of election year. However, the turnout gains over 2015 were strongest in more affluent areas. The neighborhoods with the largest turnout gains included Magnolia, Loyal Heights, Phinney Ridge and Green Lake. Lower-income and renter-heavy areas generally saw the smallest gains across the city. This is not rare: These areas are rich with the sort of medium-propensity voters who vote in only some primaries. All said, turnout increases were actually lower in areas where Oliver performed well.

Looking at individual voter records tells a similar story. Among voters who cast a ballot in Seattle’s 2017 primary, 30 percent had a perfect record of voting in the past four primaries, and a full 85 percent had at least some recent primary voting history. None of these numbers are especially unusual. It also does not appear that there was an unusual bump in the number of young voters, non-white voters, or voters living in renter-heavy areas. The electorate was rather typical.

This is not, to be clear, a criticism of Oliver’s campaign. My point is that even an effective campaign like Oliver’s faces daunting structural challenges. Voters are mostly creatures of habit. Especially in local campaigns, it’s difficult to persuade them to change their habits en masse. While this isn’t a deal breaker for populist campaigns — Kshama Sawant did just fine in the 2015 primary for her district’s city council seat — it is certainly no help. At least under our current electoral system, insurgent candidates like Nikkita Oliver will probably continue to face an electorate less revolution-minded than Seattle as a whole.