It looks like Watergate, it smells like Watergate, but is it Watergate?

For answers, Seattle can turn to an expert, a man who worked for Richard Nixon, who was knee-deep in the Watergate investigation, and who was fired by Nixon in the so-called Saturday Night Massacre.

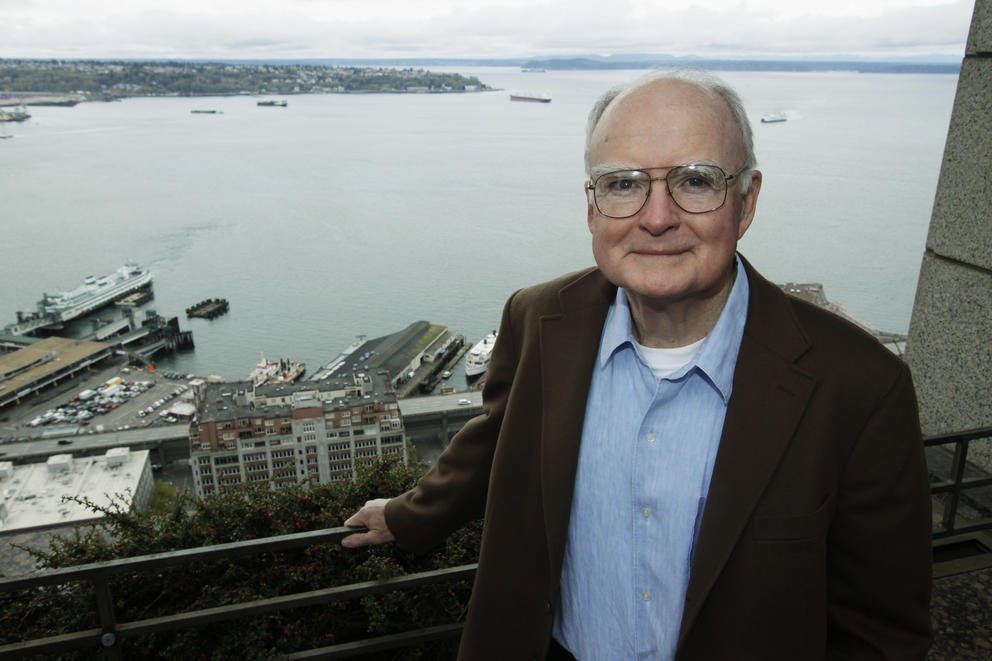

Bill Ruckelshaus, former head of the EPA, former head of the FBI, former deputy U.S. attorney general and longtime Seattle area resident now laughs at being the survivor of a “massacre” in which no one actually died. Though the Republic might have had a near-death experience.

Ruckelshaus saw the Watergate scandal of the 1970s from inside and out, and he’s still active in local politics, business and as an advocate for Puget Sound (he was an early supporter of Crosscut). But he is no fan of Donald Trump. Asked recently if the investigation of Russian influence on the 2016 election and Trump and his campaign was like Watergate, he said that, while it's too soon to know, “it looks very nefarious to me.”

Just before Congress scheduled June 8 testimony by fired FBI director James Comey, Ruckelshaus sat for a conversation at Folio in downtown Seattle about Watergate, then and now. He is tall and slender with the quiet dignity of an elder (he’s in his mid-80s) Gary Cooper, the very image of a straight shooter. He was interviewed by former reporter, columnist, author and commentator Morton Kondracke, now a Bainbridge Islander, familiar to many for his years as a pundit on The McLaughlin Group where, then and now, he exudes an intense sincerity. They discussed the parallels and differences between Nixon’s scandals and Trump’s.

The White House story is very fluid, Ruckelshaus says, with each day bringing new revelations, leaks and potential new angles or crimes. Watergate took time to roll out, too, with much digging by the media and formal investigations. Some Watergate crimes were committed after the burglary that started it all (as they say, the cover-up is often worse than the crime). Today, he says, “The story changes every third or fourth hour." The lawyer Ruckelshaus says more facts are needed.

The pursuit of those facts will likely be a long haul. Trump probably won’t quit. Nixon resigned rather than face impeachment by the U.S. Senate and put America through that trauma. Ruckelshaus said they negotiated with Nixon’s Vice President Spiro Agnew to resign rather than be tried for non-Watergate related bribes he took in the White House basement. Could Trump be coaxed to leave if things look worse? Ruckelshaus doesn’t think there is a case for invoking the 25th Amendment, removing a president if they are crazy or incapacitated, and says that Trump has shown “he will not give up easily.”

Firing Comey, director of the FBI, is one similarity between now and Watergate. Ruckelshaus is a big Comey fan despite, he said, mistakes he might have made during the 2016 presidential campaign. He thinks Trump's move echoes the firing of Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox who was in charge of the investigation of Nixon. Attorney General Elliott Richardson and Ruckelshaus, Richardson's deputy AG, were also fired when they refused to carry out Nixon’s order to dismiss Cox.

Nixon had promised not to fire Cox unless he committed “extraordinary improprieties,” which he had not done. What he had done is try to get ahold of Nixon’s White House tapes. As Ruckelshaus points out, the “massacre” outraged the public and backfired on Nixon who wound up facing a tough new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, who got the tapes. In Trump’s case backlash over the Comey firing increased media scrutiny over the Russian investigation, and Trump wound up with something unanticipated: a tough special counsel in Robert Mueller, former FBI director, to oversee the investigation into his campaign and administration. Nixon made his Watergate woes worse by his behavior. Trump seems to be doing the same.

There is no smoking gun, yet. During Watergate, Ruckelshaus said he took the job as acting director of the FBI after he was assured by Nixon of the president’s innocence. “It was a big shock to me, how involved Nixon was,” he says. After reading transcripts of testimony, he became convinced that Nixon was guilty. The Watergate tapes removed all doubt that there was a cover-up conspiracy run out of the Oval Office. Tapes, transcripts and detailed testimony have yet to emerge in Trump’s case. Not that they won’t, though given Trump’s strong base of support and a GOP Congress, the evidence might have to be a smoking cannon.

The public's response to facts matters most, he believes. Ruckelshaus says that impeachment is not yet in the cards. For one thing, the Republicans control Congress; during Watergate, the Democrats did, and during Bill Clinton’s scandal, the GOP did. He points out that the Constitution is somewhat vague on the question of what is impeachable. “Nobody knows what high crimes and misdemeanors means,” he argues. “Impeachment is not a legal issue, but a moral issue," he says. “You can be impeached for what ever the public thinks is impeachable,” whether it’s a crime or not. You’ll need both hard evidence of an outrage and public outcry.

Ruckelshaus thinks that if anyone can find a smoking gun, it’s Robert Mueller. But it will take time — and time is both friend and foe. The downside, he says, is that the longer things drag on, the more the public gets used to the accusations and starts to shrug its shoulders. Outrage at the beginning of the Monica Lewinsky/Bill Clinton revelations eventually became a kind of “these things happen” story. “People get tired of it.” Trump’s best strategy is to draw out the investigation until the charges lose their charge.

The Big Picture is worrisome, but with a silver lining. Asked about his broader concerns, Ruckelshaus worried about the long-term declining in faith in the government and its institutions. “If the public doesn’t fundamentally believe in institutions…democracies don’t work very well.” He warns that trust in institutions has been eroded to “practically zero.” Worse, "We have a president who says they shouldn’t be trusted.” Silver lining: “One good thing: people are really paying attention to politics,” he says. He encourages people not just to complain, but get into public service, or be involved. “Get in the boat and row,” is his advice.