It’s quiet in the Greg Kucera Gallery but the silence is thick with stories. Laundry women fed up with brutal plantation owners. Slaves endlessly hoeing fields. Landscape guys irritated by racially-loaded lawn ornaments. “¡Cuidado! – The Help,” the new art show up at Kucera's Pioneer Square gallery, isn’t just about the low wages, humiliation and sheer labor of those hired as “help.” It’s art about a system that links ethnicity, class and capitalism — and it talks loudly.

“The big problem in America is understanding workers as real parts of the population,” says photographer/videographer Rodrigo Valenzuela. “We need to do as much as we can to talk about that, to…make everyone part of the same class.”

Valenzuela, a Chilean-American artist who floats between Seattle and L.A., ought to know. The artist was once an undocumented worker in the construction industry; his art deals with bringing worker’s reality and media imagery face to face. In “¡Cuidado!” his two short documentaries Prole and Maria TV feature construction workers and Seattle hotel maids in front of a camera telling their real-life stories; but the people are also cast as characters in a telenovela. The videos highlight the gulf between real people and media images of them, between object and subject. But the films also do what every other piece in this show does: shines a light on the actual people behind the job description of nanny, yard worker, maid.

“We wanted to do the show last summer when Trump was hot on the campaign trail,” Kucera explains. “When he was all about ‘sending illegals back.’”

The show's title — ¡Cuidado! — means Watch out! in Spanish. Kucera says it's a call to viewers to Watch Out and pay attention to those who are often marginalized.

It took until now to get all 12 national artists and 32 works lined up, Kucera explains, but the timing is possibly even better now given Trump's policies singling out immigrants and undocumented workers. It also allowed for some specific works to be made for the show, including Seattle painter Roger Shimomura’s woodcut-style acrylic showing the artist as a teen dressed in a kimono and mowing the lawn while Barbie-pink women lounge around a pool.

There’s plenty of irony, too, in Betye Saar’s Waiting to Serve series. The iconic Los Angeles artist (now 90) paints vintage serving trays blood-red, pasting them with a collage of 20th Century stereotypes of African American hotel workers: beetle-browed bellmen, crow-headed waiters. Juventino Aranda, a Walla Walla mixed-media artist whose work centers on cultural and art-historical re-appropriation, blends irony with the surreal: a white cement sculpture of a man in a sombrero stands next to a donkey. It's small in scale — you feel enormous next to it. It's also uncomfortable to look at.

“These images are what always come up in Cinco de Mayo or other events where Mexican culture is overexploited,” says Aranda, who with his family has done landscaping work. The point he's making here: take what might seem like a funny, cute garden sculpture but consider what your brown-skinned gardener might feel.

The show also features Aranda’s giant glass mirror. He’s etched it ‘70s style with a sunset-and-palm tree scene, then framed it in a cast-bronze replica of a cheap gilt frame. The whole thing is wrapped in cardboard: tacky but prized "art." It's a juxtaposition of luxury and the low-income labor that sustains it.

“It reminds me of the neo-economics of the Reagan administration, where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer – that Mar-a-Lago dream,” says Aranda.

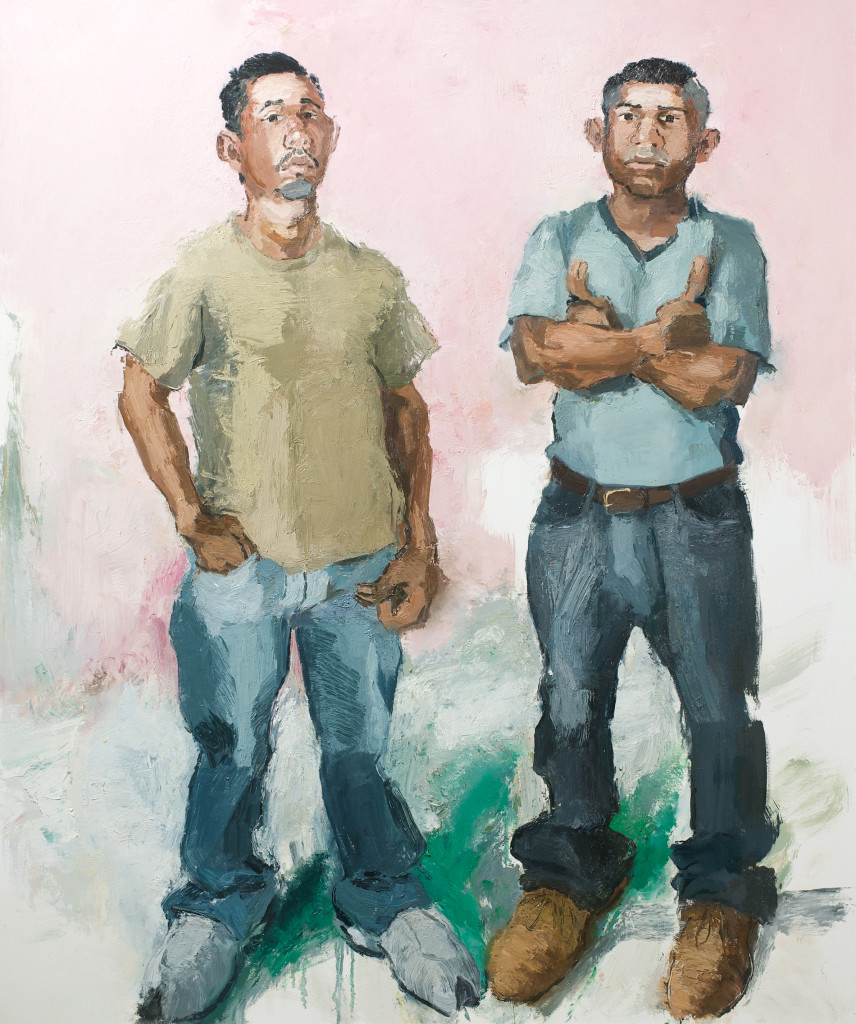

But there’s also work that speaks with a breathtaking directness. John Sonsini’s huge oil portraits of workers take up an entire wall. The L.A.-based Sonsini has been doing this work for decades, hiring day workers to do nothing but pose for portraits; he records the workers' unease, uncertainty and sheer humanity. Ramiro Gomez, an L.A. artist who once worked as a nanny, creates soft acrylics of real domestic workers painted atop pages from glossy home-and-garden magazines. Pastoral, by Kara Walker, the New York artist known for her race-based silhouettes, shows a black figure painted directly onto a wall: a slave hidden underneath a sheepskin trying to 'fit in.'

But the other element of the show is how historical narratives of labor and injustice play into contemporary systems. Patrick Kam’s Dragon Irons – vintage laundry irons with long cords – crawl across the floor, forever tethered to their suitcase like immigrants still bound by misconceptions and stereotypes. Lynne Yamamoto’s RingaroundaRosie installation has starched men’s shirt sleeves jutting like fists from the wall, references to both her grandmother’s experience as a laundry worker on a Hawaiian sugar plantation and our current structures of gender and race.

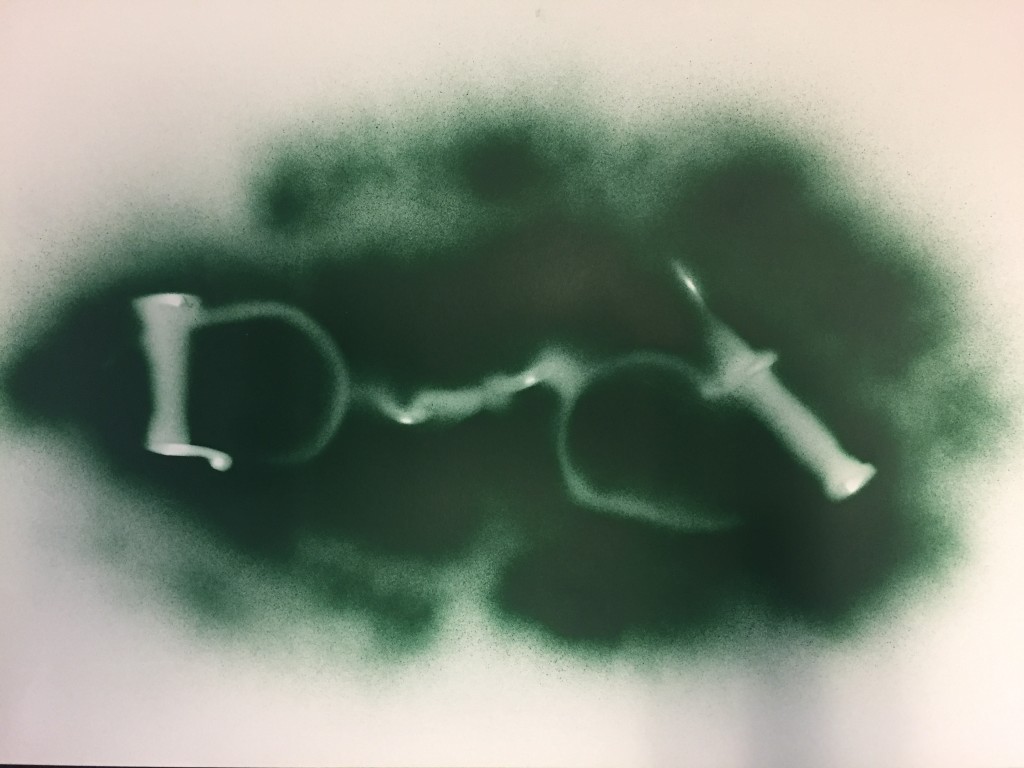

Paul Rucker's installation When We Were Useful includes both his own looped cello music and a video showing animated slaves working the fields. Then the camera zooms out, slowly revealing the slaves' endless work atop an 1862 Confederate dollar bill. Shown with his Forced Migration Series – green acrylic stencils of slave shackles – the works speak powerfully about labor injustice.

“Prison labor is no different from slave labor,” says Rucker, a Seattle artist whose career in combining socially-charged art with his own music is soaring with a recent Guggenheim Fellowship. “There are 2.2 million people in prison in this country, and companies are benefitting from their labor…People are unaware of our history as a country of forced labor and immigration. That’s what makes this community vibrant, and a lot of people very wealthy…We would not have America as we know it without these workers.”

So is “¡Cuidado!” a show to educate white folks?

“I’m not thinking about that,” says Kucera. “The show is aimed around people who are recipients of low wages, poor jobs, bad attitudes. And the goal is to show artists from our region in the context of other artists engaged in similar work.”

Valenzuela agrees.

“I don’t have a target audience,” he says. “People who have a bit of empathy, of understanding – that’s the audience. It’s about labor, about the human factors of being a worker.”

Says Aranda: "Art itself, whatever period you look at, has always been a form of dissidence visually. It’s a form of response.”