The Monorail isn’t supposed to be here.

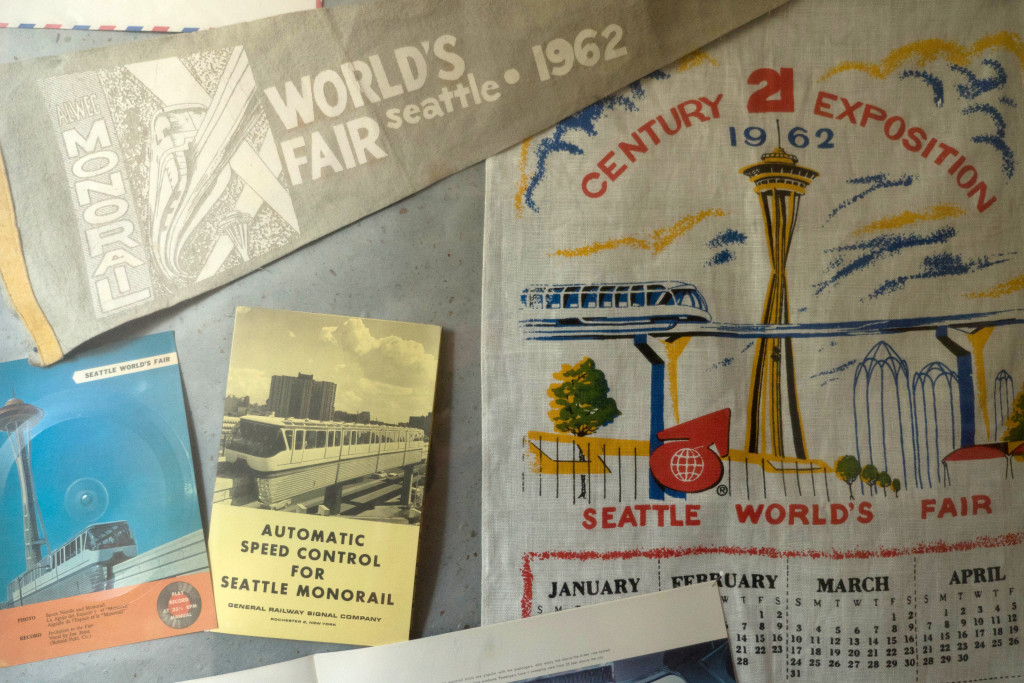

It was built as a demonstration project for mass transit for the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair and was originally slated to come down after the exposition. Ideas to expand it came to naught. In the early 2000s, when monorail mania revived in Seattle, it was going to be demolished for a new “Green Line” as part of a new citywide monorail system, until the voters pulled the plug on the plan.

Despite challenges, the Monorail is not only still standing but arguably is more essential than ever with an important role to play in the remaking of Seattle Center. As the city considers two half-billion dollar proposals to remake KeyArena into a world-class concert and NBA/NHL venue, the Monorail comes up as a critical part of any transportation plan getting people to games and events.

At 55 years old, rather than frail, the Monorail is pretty robust. The trains are maintained in a cramped underground space under the Seattle Center station. Many of the parts are off-the-shelf technology, such the rubber tires it runs on that come not from some futuristic lab but Les Schwab. Good, durable design has kept the Monorail going.

I got a sense of that as I sat in the driver’s seat of the Blue train recently. I noticed two things. First, the control panel is a computer screen that displays the number of miles the Monorail has traveled since the beginning: more than 1.3 million. That’s a bit more than the odometer reading on a used Volvo. Second, as I pushed the joystick forward to make the train go I could feel its strength. With 700 volts of electricity powering it, the experience was Jetsons-like: smooth, quiet, zippy and far above the madding crowd. The train feels anything but antique.

According to Seattle Monorail Service, the private company that operates the system for the city, the Monorail is still a workhorse. During the six months of the world’s fair, the Monorail’s two trains, Red and Blue, hauled some 8 million passengers. The annual haul in 2016: 2.2 million. The Monorail operates 363 days a year and is self-sustaining.

While today’s annual demand is smaller than in ‘62, it’s still significant. For big summer weekends like Northwest Folklife and Bite of Seattle, the trains carry up to 22,000 people per day. Its current maximum capacity is about 6,000 per hour (3,000 in each direction). Monorail general manager Thomas Ditty tells me the busiest 45 minutes of the year follows the New Year’s Eve fireworks show at the Space Needle as they convey “the cold, wet and intoxicated.” And servicing the KeyArena is nothing new: the Monorail carried Sonics fans when the team was here before and they still adjust operating hours to work overtime to accommodate KeyArena events, from wrestling to pop concerts.

Still, there are improvements that could expand capacity and alleviate traffic and parking challenges if KeyArena gets more use.

Getting people on and off faster is a major point of improvement. Accepting ORCA cards, selling e-tickets or selling Monorail tickets as part of other event passes (buy a concert ticket that includes a Monorail ride) would help. Having to move everyone through the old ticket booth bottleneck is inefficient. The Monorail, in fact, is already working on moving to electronic payment.

Stuffing more people in the cars is not viable — current train capacity is about 250, with seats for 110. That’s fewer people than used to cram in during the world’s fair. But in 1962, there were no ADA requirements, folks didn’t lug backpacks or push strollers the size of small SUVs. People are also bigger now. Ditty also notes there is an increased number of passengers with luggage because they can quickly link from airport light rail to the Monorail to get to cheaper hotels near Seattle Center. “They can save $80 per night,” he says.

Eventually, light rail will go right to Seattle Center, but people often forget there is already a direct link between Westlake Station and the Westlake Center Monorail station (via elevator). Upgrading the “vertical connection” with a bigger, faster elevator or adding a second one would facilitate getting people from the tunnel to the Monorail station quicker. Better elevators, better stairway-to-tunnel connection and reduced ticket booth gridlock could speed loading and unloading significantly, Ditty says.

Expanding Westlake’s Monorail platform would also help. This has been considered before, moving it out or lengthening it. In the 1990s, one idea was to have it connect to what is now Nordstrom’s flagship store. This is conceivable because the two Monorail stations, the rails, and the support pylons are not protected by the Monorail’s 2003 landmark designation. Only the cars are fully protected by the preservation ordinance. Meaning, station and track improvements could be made without running afoul of restrictions.

The original Westlake Monorail station was torn down for Westlake Park. It was designed so both trains could load and unload simultaneously. The current configuration only allows one train in Westlake at a time. When the station was moved into the new Westlake mall in the late 1980s, the Monorail tracks were moved at a bend that created a section now called “the gauntlet” where the two trains cannot pass each other without colliding, which happened in 2005.

The pinch point hurts turnaround time. If the Westlake station platform was redone and the gauntlet removed you could maybe double the Monorail’s capacity from 6,000 to 10,000 or 12,000 per hour, according to the Monorail’s director of marketing Megan Ching.

Both bidders on the KeyArena makeover, Seattle Partners and Oak View Group, have said that boosting Monorail capacity is crucial to their plans, though their bids do not include those costs. Presumably, they would be borne by the city of Seattle, Sound Transit, King County, private investment or some combination.

The Monorail in Seattle has had a somewhat bumpy ride but has proved to be resilient. With some tweaks, investment and ingenuity, it can continue to carry a big load when it comes to Seattle Center’s future.