This story was originally produced for EarthFix.

Two toddlers run around Sally Garcia Acosta’s house. They squeal as they take their toy cars for a spin — to the living room, through the den and around the kitchen corner.

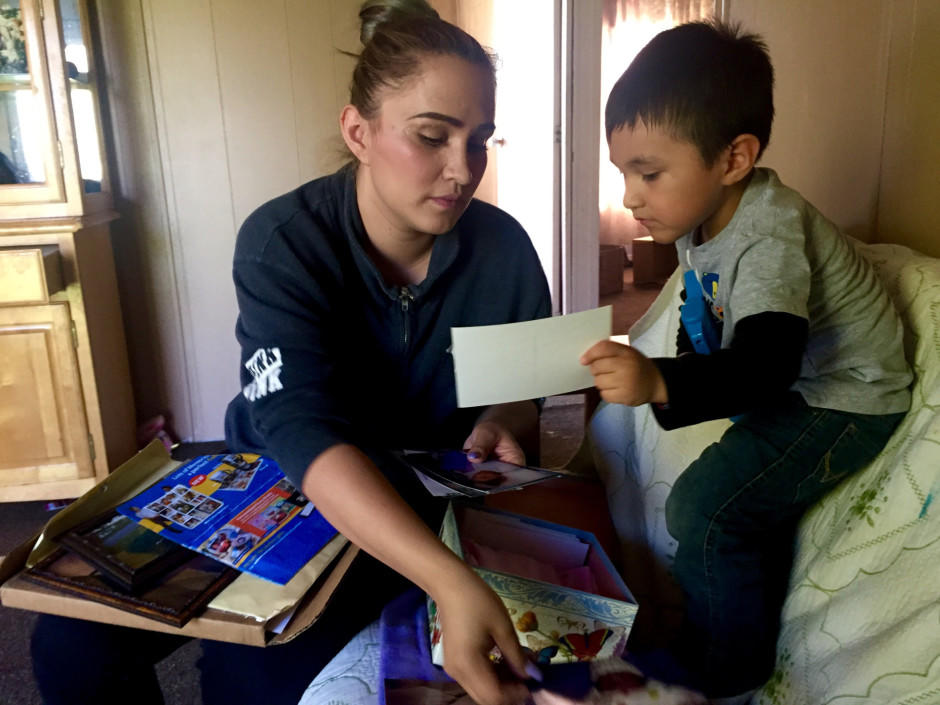

Garcia Acosta sits on the couch beside a small butterfly-adorned box. It holds some of her most sacred belongings: memories of her deceased daughter, Maria Rosario Perez.

“This is her little blanket that she had in her little bassinet that they have at the hospital,” Garcia Acosta said as she smooths out a soft purple blanket.

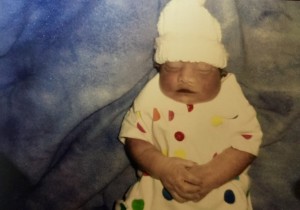

Garcia Acosta lifts a polka dot dress from the box. It’s way too big for Maria’s tiny frame — she weighed 3 pounds 6.6 ounces when she was prematurely born.

“It was the smallest thing we could find on short notice,” Garcia Acosta said.

Maria Rosario Perez lived for a few short hours after she was born. The cause of Maria's birth defect, anencephaly, is still unknown.

Maria was born with a rare and fatal birth defect called anencephaly. It’s striking at an alarming rate — about four times the national average — in three Eastern Washington counties.

The condition leaves babies who survive to term without their skulls and brains completely formed.

“It’s hard,” Garcia Acosta said. “You have this hope that you’ll have the baby — you’re going to get to enjoy them. You’re going to get to see them grow up. Then out of nowhere, it’s taken away from you. And there’s nothing that anyone can explain. To tell you why.”

‘I’m thinking, this is bad’

Nurse Sara Barron was the first to raise the alarm. In 2010, she worked at Prosser Memorial Hospital, where she said, they delivered maybe 300 babies per year. In a two month period, she said two babies were born with anencephaly.

“And I’m thinking right then, ‘This is bad,’” Barron said. “I’ve been a nurse for over 30 years. I saw one case 30 years ago when I was in nursing school; one case 12 years ago at another hospital; and now I’ve seen two in two months at this little, tiny hospital.”

She talked to other healthcare workers in the area. They’d also seen an increase in anencephaly cases.

Anencephaly is a type of neural tube birth defect — spina bifida is another on the neural tube spectrum. (Spina bifida rates are about the same as what’s expected in the area.) Neural tube birth defects happen very early on in pregnancy, likely before women even know they are pregnant.

Barron alerted the Washington State Department of Health. After digging into the birth statistics, epidemiologists found elevated rates of anencephaly cases in Benton, Franklin, and Yakima counties in the Yakima River Basin.

But why?

State epidemiologists called in the Centers for Disease Control, studied literature reviews, and held listening sessions in Eastern Washington to get a handle on possible causes. They formed an advisory committee to follow-up on what they were discovering.

Investigators eventually interviewed 17 mothers in the area who had a neural tube-affected pregnancy. Twelve of those pregnancies were affected by anencephaly.

From 2010-2017 there have been 45 documented cases of anencephaly in the three counties.

Ruling things out

The investigators ruled out every concern that came to their attention, most prominent:

- Radiation from Hanford. Department of Health investigators found accidental releases have decreased over time at the Hanford nuclear weapons complex, and any release would most likely contaminate the soil and water.

So the team wondered if the women got their drinking water from the Columbia River. They found the mothers live in such a wide area that it’s unlikely they all got water from the Columbia.

- Nitrates in drinking water. Most all the mothers in the control study and those with neural tube-affected pregnancies — about 80 percent — got their water from public supplies and not well water, where nitrates in drinking water can be high in the Lower Yakima Valley.

To complicate matters, investigators weren’t able to completely rule out some combination of nitrates in drinking water and nitrosatable drugs.

“It’s been studied for literally decades, and the science still isn’t perfectly understood,” said state epidemiologist Cathy Wasserman.

- Pesticide exposure. This was harder to vet, mainly because there are so many ways to be exposed to pesticides and so many chemical combinations. Investigators were unable to 100 percent rule out pesticide exposure.

But after looking at where women worked, how closely they lived to agricultural fields, and what chemicals are used in Washington, investigators were unable to find any single exposure to reduce among all of the women.

In the end, after six years, they couldn’t find a single cause. Wasserman, the epidemiologist, said cluster investigations are notoriously difficult.

“It’s really disappointing for us to not be able to say this is what we learned and this is what we could do to prevent heartache and tragedy from affecting families,” Wasserman said.

The state is going to continue monitoring pregnancies with anencephaly through next January.

Environmental factors?

But some people think there’s more that could be done.

Sara Barron, the nurse who originally reported the elevated levels of anencephaly, wonders if there might be more connection to rural areas.

She pointed to a map on her computer screen. Barron said other anencephaly clusters across the country also appear to be in less populated areas.

“In our counties, it was the farmworkers as well as the farm owners that were getting the anencephaly. It was not economic. It was not race. It was not necessarily by diet. So there’s something else out there that’s related, and we don’t know what it is,” Barron said.

That leads her to believe there are environmental factors at play.

It’s rare for a cluster investigation to get this far — usually it’s easier to rule out potential clusters. In the past decade, health workers said they don’t remember this lengthy of an investigation in Washington. In Texas, which has an in-depth birth defect database, there have been five investigations of this depth over the past 20 years.

Peter Langlois was on the Washington investigation’s advisory committee and helped set up the birth defects registry for the Texas Department of Health. One of the more widely reported anencephaly clusters happened in that state’s border city of Brownsville in the early 1990s.

Langlois said there is still a lot to learn. Not much is known about anencephaly, overall.

“We absolutely don’t (know everything),” Langlois said. “In fact, with birth defects in general, we don’t know what causes most of them.”

He thinks, in the future, combining genetic information with environmental factors could provide some answers.

Reducing the risk

One thing that’s certain about anencephaly: women of childbearing age can help reduce their risk by taking folic acid.

Dr. Lisa Galbraith is an obstetrician and gynecologist in Prosser. She’s treated several anencephaly-affected pregnancies.

After seeing four such cases in one year, Galbraith said she asks every woman she sees about the vitamins they take.

“It’s become a very important part of my practice. My line usually is, ‘You know, we do have increased risks of anencephaly in this valley, so let’s do everything we can to make sure that doesn’t happen to you,” Galbraith said.

All of this attention has led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to fortify corn masa with folic acid. The March of Dimes has also helped spread the word about folic acid supplements.

Sally Garcia Acosta has taken folic acid during all of four of her pregnancies and increased the amount she took after what happened with Maria.

She hopes there will be answers some day.

“It’s frustrating. I figure it’s not only my child, it’s happening to other people, too,” Garcia Acosta said. “If no one talks about it, and everyone pushes it aside, it’ll never get figured out.”