Seattle’s homelessness problem — the population is ranked the third largest in the U.S. — has inspired a myriad of creative attempts at solutions such as tiny home villages and safe consumption sites. A new effort, Seattle architect Rex Hohlbein’s BLOCK Project, seeks to allow Seattle residents to help from inside their backyards.

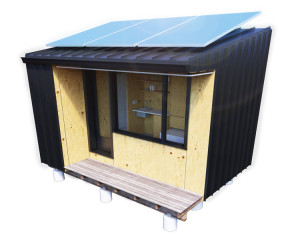

The project aims — eventually — to put a 109 square foot home in the backyard of one single-family lot on every residentially zoned block within the City of Seattle. Completely self-sufficient with solar-panels, a greywater system and a composting toilet, the BLOCK houses will have a shower, a sink, a small kitchen counter and a place to sleep.

What’s innovative about the project lies not only in its original architecture, but in the way it tackles societal conceptions and stereotypes of homelessness itself.

“The BLOCK Project takes the idea of someone being marginalized and turns it on its head,” said Sara Rankin, an associate professor and director of the Homeless Rights Advocacy Project at Seattle University School of Law. “It makes the person who was previously experiencing homelessness the center of the community.”

Rankin doesn’t see the BLOCK project as a resource-remedy– it won’t replace the need for more low-income housing. Nor would it fit everyone’s situation or provide housing that would work over the long term for most people. Instead, it breaks down some of the social distancing that exists between the housed and the unhoused. “We know social distance influences how people relate, and the way people in power allocate rights and resources,” said Rankin. “things change when you know someone who’s been affected by the problem.”

The social integration aspect of the BLOCK Project distinguishes it from congregations of tiny homes such as Othello Village. “From my vantage point, and from what history has clearly demonstrated, concentrating poverty in housing projects does not work,” said Tristia Bauman, a senior attorney at the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. “Distancing people contributes to racial segregation, and generational poverty.”

The BLOCK project is unique in that it doesn’t separate out people experiencing homelessness. By integrating them into neighborhoods of opportunity, they have the same access to public transit, jobs and good schools.

Decreasing the social and physical distance between neighborhoods and homeless folks also makes city residents more likely to form moral and emotional associations with the issue of homelessness — which translates into awareness of laws and policies that deal with mental health treatment or decriminalizing homelessness, said Rankin.

To creator Hohlbein, it’s an issue of proximity. “The closer you get, the more you feel, the more you want to get involved and change it,” said Hohlbein.

So far, four households have signed up to host a BLOCK resident and are preparing to be hosts, and 22 other households have expressed interest. Two future hosts, Beacon Hill residents Dan Tenenbaum and Kim Sherman, say they received nothing but support when talking to their block about the new neighbor. “We’re just excited to have another member in our community,” said Sherman. “We can’t wait to welcome this person into our community and get more involved in our community at large.”

Both hosts and residents (with assistance from a social worker) fill out questionnaires to ensure they’re compatible. Sherman likes to garden and Tenenbaum is a musician, so they’re hoping to share those passions with their future backyard neighbor.

Although still ironing out the details, Hohlbein said hosts and residents will sign an indefinite rental contract. “Everyone who has experienced homelessness is facing trauma,” said Hohlbein. “And people heal at different rates. We don’t want to get in the way of that.” The indefinite contract is intended to allow residents to take however much time they need to move on to other housing — or decide to stay.

Tenenbaum and Sherman are fine with the idea that their backyard neighbor could be a permanent addition. “If they were to stay here forever, it would probably mean that it’s a good arrangement, and that would be great,” said Tenenbaum.

The BLOCK Project follows the launch of a project in Portland where county officials are offering to build a tiny home in homeowners' backyards if they agree to house a homeless family. Although drawing upon the same backyard principal, the Portland project only accepts families and has five-year contracts.

To find something that draws upon the same principles of social integration and uninterrupted healing as the BLOCK project, you have to look all the way to Belgium. Hohlbein said the small, charming town of Geel is the closest thing he’s seen. For over 700 years, residents of Geel have accepted people with mental disorders into their homes and cared for them. The people aren’t considered patients, but are welcomed into the lives of hosts and the town’s community.

Like the town of Geel, Bauman believes, the BLOCK project can have a significant and long-lasting impact. “This is not a Band-Aid,” said the National Law Center’s Bauman. “A Band-Aid is an attempt to address homelessness that will never get at the roots of what causes it. But this project, where it could amount to a permanent housing option, that’s part of a solution.

It will take other approaches to end homelessness in Seattle, she added, “But this could be a really innovative part of that solution.”

For hosts Tenenbaum and Sherman, the most exciting aspect of the project isn’t in terms of number of units or individuals that will be served, but how it will more broadly impact societal views about visible poverty.

“This is bigger than just us, our backyard, and the one person that’s coming to live here,” said Sherman. “Essentially, we’re putting up walls to break them down.”

—

This series made possible with support from Northwest Harvest. The views and opinions expressed in the media, articles, or comments on this article are those of the authors and do not reflect or represent the views and opinions held by Northwest Harvest.