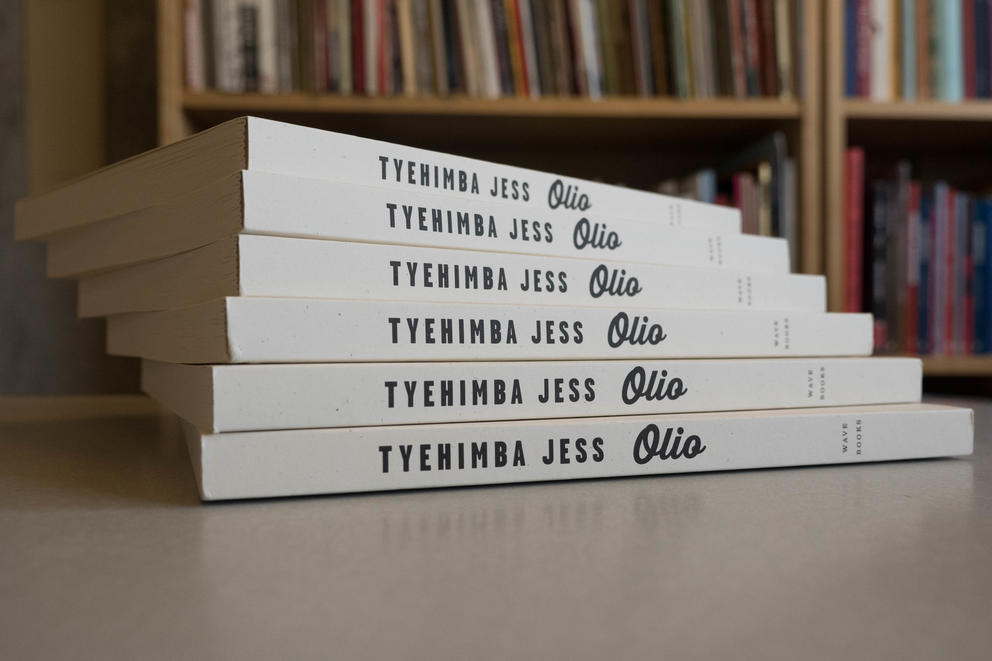

When the staff at Seattle poetry press Wave Books learned they had won a Pulitzer Prize on Monday for the book Olio, by Tyehimba Jess, it wasn’t via black-tie ceremony or hand-delivered scroll with wax seal.

“We saw it on Twitter,” says Ryo Yamaguchi, publicity and marketing director for Wave, where the morning after the big win, upbeat jazz wafted from speakers and the sole office phone’s blinking red light foretold congratulations. In fact, the news was “four retweets deep” before, incredulous, Yamaguchi dared to share it. First, he had to make sure it was true. So he speed-researched it online in Wave’s compact, tidy Eastlake space that sits between low-slung houseboats and massive fishing vessels bound for the Bering Sea.

Founded in 2005 by Seattle arts patron and businessman Charlie Wright, Wave is a small but acclaimed press that over the last decade has piled up accolades and awards from national literary outlets. It’s perhaps not surprising that it has earned the respect of the local literary community as well, including a Stranger Genius Award nomination last year.

Seattle is an unabashedly pro-poetry town, with a poetry bookstore (Open Books), a civic poet (Claudia Castro Luna), a youth poet laureate (Angel Gardner), a decades-old poetry press (Floating Bridge Press) and a brand new one (Gramma Press), not to mention a vibrant poetry slam community and the popular Poetry on Buses program. It makes sense that this city would be able to add a Pulitzer Prize for poetry to that list.

Senior editor Heidi Broadhead was on vacation in South Carolina when she got the call. “I was standing on the beach with my son when my phone started buzzing like crazy,” she says. She was one of three Wave editors to shepherd the book to publication, including Matthew Zapruder, editor at large, and Joshua Beckman, editor in chief.

She says when Zapruder initially brought the book concept to Wave, he described it as a “variety show” in print. As the third editor to review the book, Broadhead’s role was akin to producer, “ensuring that [Jess’s] vision was translated to the page.”

Ten years in the making, Olio is astoundingly innovative, combining poems, songs, historical facts, fiction, interviews and tables to create a chorus of compelling voices — all singing praises for the countless African American performers whose contributions to minstrel shows of the late 1800s have been largely undocumented. Detroit-raised and New York-based Jess plays with a multitude of poetic forms in Olio (the word means a hodgepodge, and in the 19th century specifically referred to a miscellany of musical acts), as well as unusual book design, including several fold-out pages that literally cause readers to change their perspective.

“We thought, ‘people are going to love this,’ because we love it,” Broadhead says. “Of course, we read poetry all day every day.”

But despite Olio’s radical departure from standard poetry collections, the book has been heralded in part for being highly accessible. “It’s not that difficult to get,” Broadhead says. “It’s almost like reading a novel—there’s a strong narrative pull.”

Yamaguchi agrees. “The innovations are immediately graspable,” he says. He believes Olio appeals to people who don’t necessarily consider themselves poetry fans, which can only lead to good things for poetry on a larger scale. “People who read and enjoy it may take an interest in other titles Wave has published, or in other poetry books.”

As for Wave’s staff celebration, it will have to wait. At the moment, the editors are all in different cities across the country, sharing their exhilaration via text messages. “We’re using emojis,” Broadbent says with a laugh, “and lots of exclamation marks.”

To read excerpts from Olio by Tyehimba Jess go here. To watch Jess recite some of his work go here.