What started out as the internet’s distraught reaction to the Trump administration's proposed environmental budget-cuts and Scott Pruitt's nomination to head of the EPA is materializing this Saturday in Seattle and around the world as the March for Science.

“The idea for the march started the day they put a climate denier in charge of the EPA,” said Miles Greb, an organizer for the Seattle march. “So there was this big emotional moment on social media, then on Reddit, where folks inspired by the women’s march began organizing the national March for Science.”

Working with national organizers, Greb gathered up a leadership team, social media groups and fundraising. What he’s built has grown into more than a chance to stand up for science.

Greb, who writes a series of science-fiction comics about science, said there are three main reasons people are marching. “Some just march for science,” Greb said. “The cold, hard methodology of science, what it means and what it can do for you.” Others will march for social justice issues and how science can affect people more directly, such as through diversity within scientific institutions. But the main frustration motivating people to march is climate change, Greb said.

Luanne Thompson, a professor of oceanography and director of the UW Program on Climate Change, wants the march to depoliticize the issue of climate change. “I want to make sure that science is used to find common ground on contentious issues like climate change,” Thompson said.

But some scientists think the march will have the opposite effect. “It’s very dangerous to mix politics and science,” said Cliff Mass, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Washington. “Protest movements aren’t going to contribute anything at this point.”

Despite the march’s explicitly nonpartisan approach, Mass said the march will contribute to the politicization of science.

“At this point, it’s clearly an anti-Trump protest,” said Mass, who is well known for his weather blog and Friday appearances on KNKX radio. “It’s too early to know what budget cuts, if any, are going to be made.”

Even considering the intrinsically political nature of people participating in the march, Greb doesn’t see the march is a partisan event. “I think it would be a danger if the march was trying to say that science is partisan,” Greb said. “Neither party has a monopoly on good ideas. We don’t have a party in America that bases all its policies on evidence and that’s our main thrust politically — to advocate for evidence-based policy.”

And some supporters of the march believe the idea of purist, nonpartisan science is a bit idealistic. “We’re all a part of this political society and to say we’re separate from it is a little naive,” said Thompson, the UW Climate Change program director. “The denial of our role in political discourse and decision-making is dangerous.”

For some marchers, it’s not so much about politics — it’s about identity. Sarah Myhre, a post doctoral scholar in the School of Oceanography at the University of Washington, said, “People ask me, when did science become political? I respond by saying, when did it become political to be a woman? I’m marching in defense of science but I’m also doing it to stand up for all the people that are a part of science who have been directly attacked by this administration. People of color, women, immigrants, refugees, people that are coming here to our country to participate in the scientific process. Those people are my colleagues.”

The Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science is partnering with the national organizing committee, saying that it "supports the core, non-partisan principles of the March for Science and their recognition that diversity in science — a wealth of opinions, perspectives, and ideas — is critical to the scientific process." Some African American scientists, however, complained to a writer for The Root that the event is too focused on the celebration of a largely male and white scientific community. Some said they found it difficult to work with the march's national leadership.

Many see the march as a chance to not only stand up for science, but for the people behind it. Thompson plans on marching without a lab coat to show what scientists really look like.

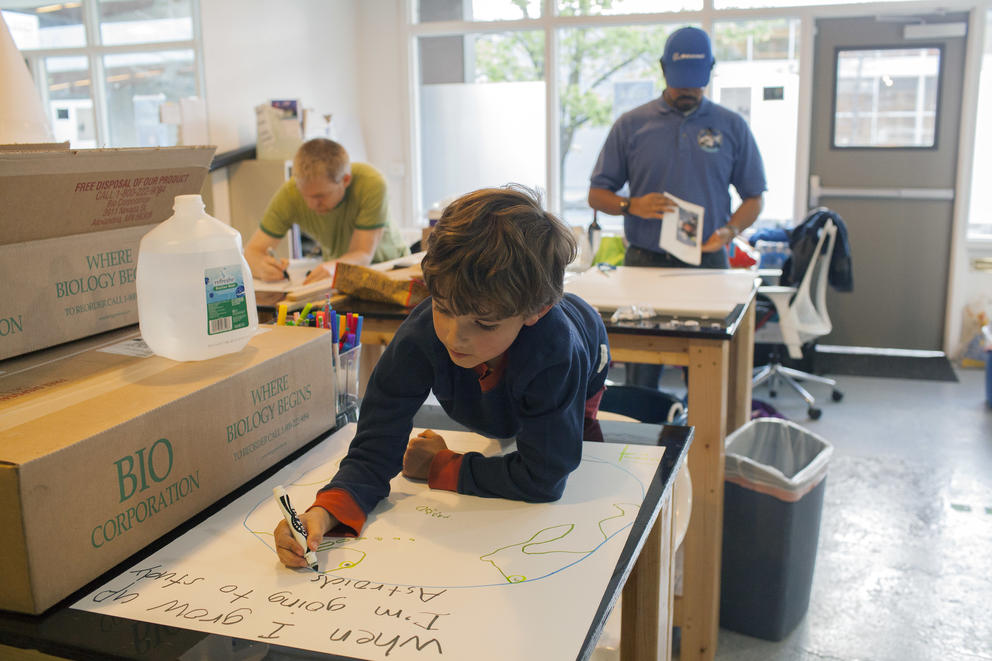

Organizer Greb says, “I believe that having scientists out on the streets where people can see them will show this isn’t just some sort of esoteric practice. I wanted to show their faces and tell their story.”

This story has been updated to correct two people's titles.