I’m feeling liberated about what I write these days.

I’ve heard from the highest sources in the land that it is now okay to present alternative facts instead of plain old, everyday facts.

Just so you know, I am tall, blonde and slender, and a Nobel Prize-winning Olympic swimmer.

I also received a majority of the vote in the last presidential election.

Freedom from facts can be a glorious thing. For a while.

To be serious, this is a critical time for facts. It is also a dangerous time. If facts aren’t facts, knowledge is impossible and ignorance flourishes. Not good in a democracy, but not so bad if you’re reintroducing a new Dark Age.

It is a dangerous time if journalism flounders — and it is floundering, faced with disruptive technological change, shifting business models, and downsizing. That’s not good for our democracy. We need a literate, informed, and motivated electorate, and constitutionally protected media that speak truth to power.

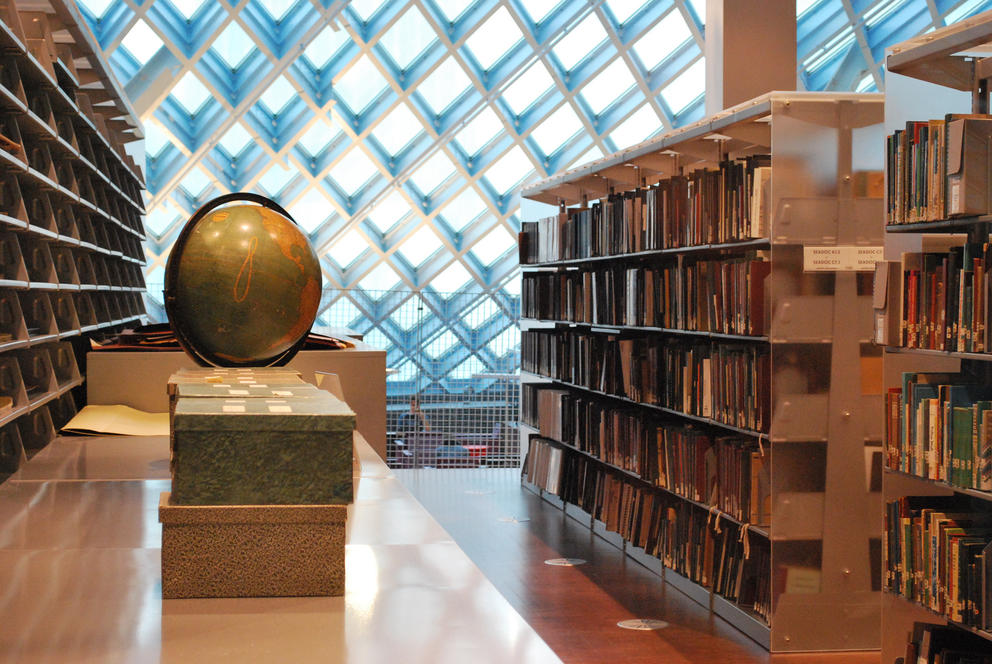

It is a dangerous time if we are not informed by history. Many of the most precious resources that feed democracy — libraries, historical societies, archives, museums — have barely recovered from the knife cuts of the Great Recession and require more resources to modernize.

To that end, the King County Council will be discussing this spring whether to put a measure on the August ballot that could raise substantial funds — perhaps as much as $68 million in 2018 — for schools and heritage groups in the county with a one-tenth of one percent increase in the sales tax. In light of possible federal budget cuts, this seems a crucial time to consider such funding, made possible by a Cultural Access Bill signed into law Olympia in 2015.

We’ve approved funding for Medic One and 911 emergency services. Now it’s the fabric of reality that needs an emergency boost.

The importance and survival of our institutions cannot be assumed. They are more ephemeral than many of us imagined, though history is full of warnings.

Ben Franklin is said to have answered a citizen’s question after meeting to draft the U.S. Constitution. What kind of government did you give us? “A republic, if you can keep it,” he is said to have replied.

What keeps a republic? Schools. The press. Libraries. Museums. Archives. Documents and databases. The people who save scrapbooks, letters, family photos and floppy disks. People with memories. The purveyors and keepers of facts.

This last year I have written about the history of fascism in the Pacific Northwest, legal controversies over historic preservation at the University of Washington, the history of our Hoovervilles and what they can teach us about the homelessness crisis today, the meaning of the crazy old Ramps to Nowhere, and the origins of some of the state’s racist place names. In doing so, I have benefitted from the Seattle Room at the Seattle Public Library, historic newspaper databases, Special Collections at the University of Washington, the federal, state and King County archives, numerous museums (the Burke, the Northwest African American Museum, SAM and MOHAI), and large and small historical societies and heritage groups around the region. Without these, we would be blinder than we are now. Facts would not be available.

If I were dictator, I would invest more resources in organizations like these. I would:

Add heritage groups to the list of road and bridge projects to be funded. They are the basic infrastructure of reality. I would make sure history is part of funding education, first and last.

I would fund more searchable databases for documents, photographs, newspapers and other collections. I would like to see these heritage groups de-siloed by creating a database that links all regional library, historical society and archive collections. Collections access needs to be upgraded.

I would provide funds for more staff, more space, and longer hours. Heritage groups need to be actively documenting and collecting the present — we live in times guaranteed to need figuring out in the future. I want history to be available 24/7/365.

I would retain staff that know collections, that are deeply experienced and trained. I have saved many man-hours when a long-time librarian has said something like, “Oh, it’s not listed in the catalog, but I know where a file of that type of material might be.” Many collections rely on a tiny number of key people to keep them going; we need to bolster institutional resilience.

I want heritage organizations to be fast on their feet, responsive, curious, to put on great programs and exhibits, to get people excited about history and culture. Many more could do that.

Journalists need facts. The public needs them too, along with context and perspective. I remain convinced that Americans have a strong appetite for truth, and it’s our job to feed it.

A different version of this column was given as a talk to the Annual Meeting of the Association of King County Heritage Organizations on Jan. 31.