The Seattle City Council’s decision on Tuesday to cut its ties with Wells Fargo over the bank’s financing of the Dakota Access crude oil pipeline was the first of its kind, but likely not the last. Similar preparations have begun in some form or another in Minneapolis, Boulder, Santa Fe and Portland. San Francisco and Los Angeles have imposed sanctions on some existing Wells Fargo accounts.

Even while Seattle progressives and other pipeline opponents lamented the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ intention to issue an easement for Dakota Access, Seattle’s move offered a bold statement that the city would not be an accomplice to a project that could trample tribal treaty rights — a project that had stalled out before President Trump signed an executive order expediting its approval.

Indeed, it’s been a nice couple of days for the local anti-Trump crowd. Last week, a U.S. District Court judge in Seattle granted the state of Washington a restraining order prohibiting federal employees from enforcing the Trump Administration’s immigration ban. Mayor Ed Murray, meanwhile, has held steadfast to Seattle’s “sanctuary city” status despite another executive order’s threat to strip it of federal funds.

You’d think the resistance was working.

And perhaps you’d be right. Redirecting investments and judicial challenges offer concrete means for blue cities and states to take advantage of the perks of federalism and reinvigorate the checks and balances they claim are disappearing from our nation’s capital. States can also attempt to preempt federal policy decisions with their own counter-maneuvers, as in the case of New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s proposal to amend the state constitution to codify Roe v. Wade in the event it’s overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court. This is uncooperative federalism.

But there’s a deeper set of questions here related to progressive cities’ economic imperatives: Should cities use investments toward political ends, or do they have only a fiduciary responsibility to taxpayers? More to the point: Does Wells Fargo even care if Seattle doesn’t bank with them? Will the city’s action ultimately make any difference?

In response to Seattle’s decision on Tuesday, Wells Fargo issued a comically indifferent statement, one painting a picture of a team of bemused banking executives. "While we are disappointed that the city has decided to end our 18-year relationship,” the statement said, “we stand ready to support Seattle with its financial services needs in the future."

And the Army Corps did grant the easement on Wednesday: The council’s decision was never going to halt the pipeline’s development. Non-nefarious banking contracts aren’t easy to come by — 17 banks are financing this particular stretch of pipeline, which is to suggest that all of them ought to be off limits for the city now (perhaps along with the other banks financing the rest of the Bakken pipeline).

There are lots of other pipeline projects out there, too, including the Trans Mountain Expansion Project in Seattle’s backyard. Will Seattle hold the implicated financial institutions accountable? Double-bottom lines to guide new banking (and investing) arrangements are notoriously difficult to quantify.

Ultimately, the council ordinance was passed on ethical grounds related to tribal sovereignty, police violence, and fraudulent accounts. We should understand the move as one of symbolism, not as one that will succeed in crippling a behemoth like Wells Fargo. And if Seattle is serious about only working with contractors “committed to and consistently demonstrate engaging in fair and responsible business practices,” as the ordinance passed Tuesday suggested, then it’s got a lot of work to do.

Messaging does hold value, though. And generally, if a city has a mandate to serve the public, and if its banking decisions or investments are producing externalities that aren't in the public interest — or are explicitly harmful to some populations — then it falls under the city's mandate not to make those investments.

Besides, “the perceived tension between investing ethically and investing to fill a fiduciary responsibility is a false one,” says Aditi Juneja, a law student at NYU and a co-founder of the Resistance Manual, an open-source platform aimed at combatting the effects of a Trump presidency. (I should disclose that I’m a team lead for the website.) She cites socially responsible mutual funds managed by the likes of Domini Impact Investments that have outperformed the S&P 500.

Juneja sees decisions like Seattle’s as part and parcel of progressive efforts under the new administration. For her, though, it’s not about “resistance” per se: It’s about the nature of governance. And whether the tools of governance are legislative, judicial, economic or symbolic in nature, they will carry social effects that reflect a city’s representative politics.

“We make these decisions when we shop at Costco because their employees get a decent wage,” Juneja says. “Cities do it with contractors all the time.” If they intend on being ideologically consistent, they ought to drive a moral stake in the ground.

And whether to counter, exact a price on, or otherwise wall themselves off from the effects of federal policies, states and cities can deploy a range of economic tools. Minnesota’s tax code, for example, allows the state to reduce income inequality to a greater extent than the federal tax code does on its own. Local minimum wage laws allow local governments to correct for passive injustices imposed by meager federal standards. Red states’ refusals to expand Medicaid furthered the narrative that Obamacare wasn’t working.

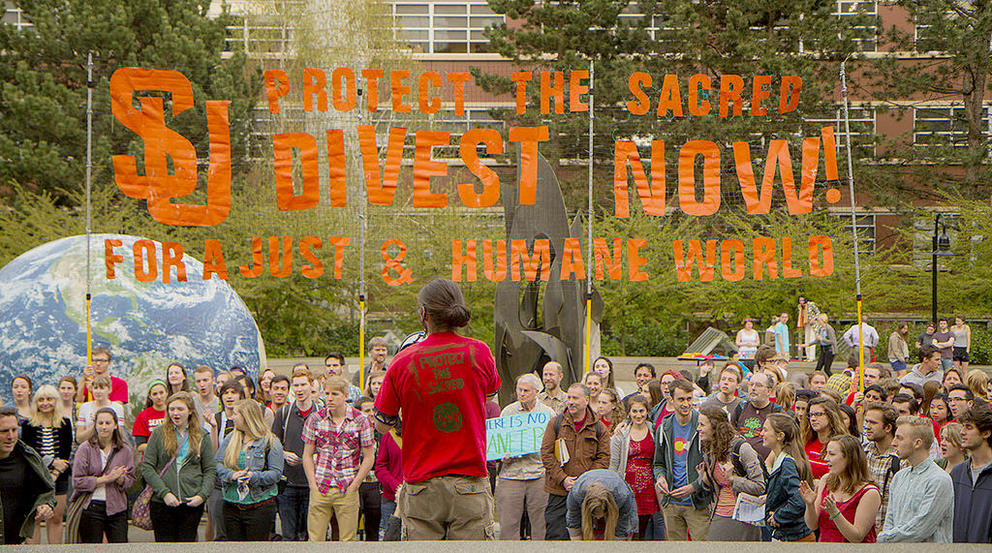

City divestment decisions — which, it’s important to clarify, Seattle’s is not; it’s a banking boycott — can, in theory, influence federal policymaking, too. Divestment proponents often point to the collective power of divesting from South Africa in pushing negotiators to the table to dismantle its apartheid system. The argument isn’t that divestment bankrupted anyone; it’s that it delegitimized the regime. Economic decisions that influence public opinion and perceptions of legitimacy ultimately can have an impact.

“This is the work of governing,” says Juneja. “This is how we get to the best outcome — how we get to what’s right and what’s just.”

And that’s true even if some of the decisions along the way are met with seeming indifference.