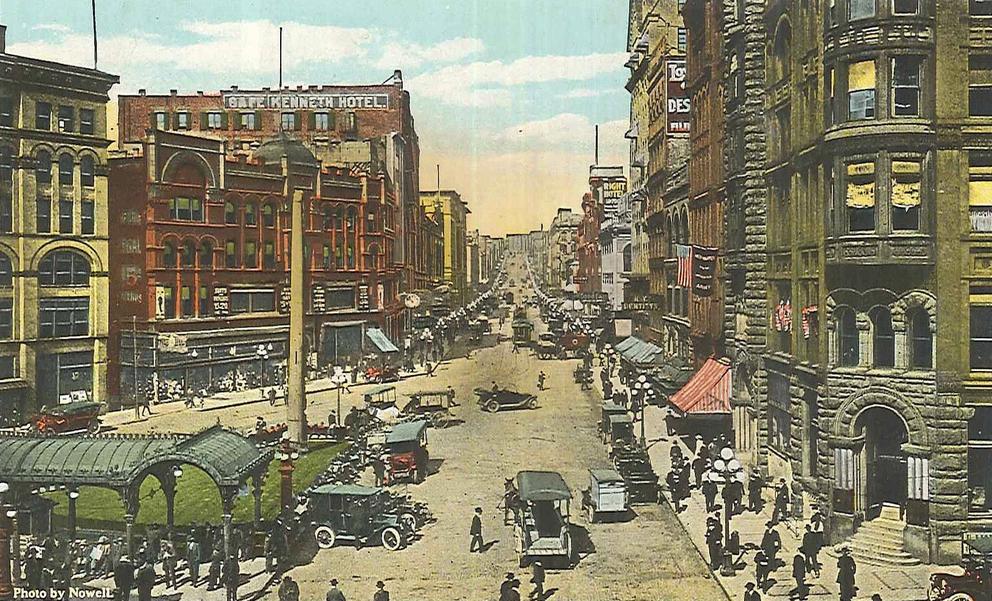

The media is full of stories bemoaning change in Seattle. Old cafes closing, landmarks demolished, efforts to save legacy businesses like that dive bar down the street. There are more construction cranes dotting the skyline than in any other city in America. Locals, the numbers suggest, have started leaving the city in droves. A group of artists has launched a new effort to generate discussion of the Seattle that was by embracing stories and places that are now the city’s “ghosts.” Danny Westneat at the Seattle Times wonders if response to the city’s unprecedented growth is a new boom in nostalgia.

Folks have long snickered at the idea of nostalgia in Seattle. They tell those of us who worry about historic preservation that the city is too young, too new, too much a work-in-progress to evoke such emotions. Nostalgia is what holds us back. It’s an Old World attitude, not a frontier frame of mind. We have been told repeatedly that the past is mere baggage, the thing we came to escape by building anew on Puget Sound.

And those folks have a point. Embrace of growth and change was in the blood of the Euro-American city founders. We attempted to remove the people tied to the “past,” namely the indigenous people who called this area home for millennia.

One of the things that struck Chief Seattle was how whites differed from his people. “To us the ashes of our ancestors are sacred and their resting place is hallowed ground. You wander far from the graves of your ancestors and seemingly without regret,” he reportedly said in his famous speech.

He observed a dangerous detachment among the whites. A difference between the two cultures was the importance of the physical environment to identity and memory. “Every part of this soil is sacred in the estimation of my people. Every hillside, every valley, every plain and grove, has been hallowed by some sad or happy event in days long vanished. Even the rocks, which seem to be dumb and dead as they swelter in the sun along the silent shore, thrill with memories of stirring events connected with the lives of my people…”

Seattle’s speech was delivered in 1854, and the earliest version of it, quoted above, appeared in the newspaper in 1887. By then, white Seattleites had already experienced their first loss associated with the emerging city’s built environment. For some of the pioneers, the chief’s speech likely had tones of loss that now had an echo for them. The pace of change was picking up, and precious heritage had been already lost.

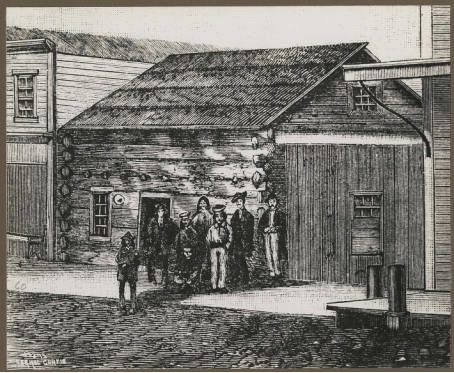

In the summer of 1866, one of the most beloved and precious structures in the city, “hallowed by some sad or happy event in days long vanished,” had been demolished. The building was only 14 years old, a small log cabin that had served as a humble sawmill cookhouse. Yet the Cookhouse, as it was called, carried the founding memories of a new city that sprang from wilderness.

Here’s how a Puget Sound Weekly story described the building as it stood before its demolition: “There was nothing about this old Cook-house very peculiar, except the interest which old memories had invested in it. It was simply a dingy-looking hewed-log building, about twenty-five feet square, a little more than one story high, and a shed addition in the rear, and to strangers and new-comers was rather an eye-sore and nuisance in the place — standing as it did in the midst of the business part of town, among the more pretentious buildings of modern construction, like a quaint octogenarian, amidst a band of dandyish sprigs of Young America.”

That description and phrasing are interesting: They suggest the frontier innovations of 1852 — when the Cookhouse was constructed — were ancient history by 1866. Seattle was still a frontier town in the 1860s, but not the primitive village of a few years previously. The comment about Young America is telling. The Young America movement of the 1840s and ’50s represented a new, Democratic ideology that advocated free trade, reform, expansionism, engagement with the world, new technologies, innovation. Seattle didn’t feature many urban dandies in 1866, but it embraced the new, not the old.

Still, the aged Cookhouse was emblematic. It was built to serve the workers at Seattle’s first permanent industrial operation, Henry Yesler’s steam-powered sawmill, in 1852. This was the business that fixed the city in its location on Elliott Bay, this was the business that put the city on the map. The small, detached cabin was near the corner of Commercial and Mill streets, now First Avenue South and Yesler Way. It was one of the first buildings built in the city, and the last of the original structures to survive. But it was much more than a lunchroom or hangout for white and native mill workers.

In notes taken by H.H. Bancroft interviewing Henry Yesler for a history of the city, the Cookhouse is described as “famous for what it was used for. … It was used, besides a mill Cookhouse, as a church, a court of justice, barracks for soldiers, a rendezvous for officers of the vessel here during the Indian war, besides being a place for church meetings, lectures, and a place where the citizens all assembled to spin yarns before huge fire.”

It was the sole, and soul, community space of the settlement. The first religious service in Seattle was held there (a French Canadian Catholic Bishop, Modeste Demers, held a mass there in 1852). It served as a hotel for people passing up or down the Sound. It was a place where itinerants could get a hot meal. It was the seat of government and site of the district court (the town’s first lawsuit was heard there), town hall, the county auditor’s office (files under a table), a storehouse and jail. It hosted political meetings, caucuses, lectures, elections and parties. “This old Cook-house … has been used for almost every conceivable purpose for which a log cabin in a new and wild country, may be employed,” wrote the Puget Sound Weekly in a long essay about the loss of the structure. “[M]any an old Puget Sounder remembers the happy hours, jolly nights, strange encounters, and wild scenes he has enjoyed around the broad fire-place … of Yesler’s cook-house.” Oh, and before his wife Sarah joined him in Seattle in 1858, it sometimes served as Henry Yesler’s bunkhouse.

In those 14 years, the city had changed dramatically. Seattle and King county had a tiny population of 302 in 1860, but by 1870, four years after the Cookhouse was torn down, Seattle had become the third largest city in the territory with a white population of 1,107. Seventy percent of the territory’s non-indigenous residents had been born in another territory, state or country. In other words, newcomers were the vast majority. Seattle’s nostalgists were a small subset of the town’s growing population, though many were still in a position of civic leadership. In any case, they couldn’t have numbered many more than could fit in the old cabin.

The writer at the Puget Sound Weekly sympathized with the feelings his pioneer readers felt for the Cookhouse, but he reminded them they must eventually “yield to the resistless laws of change.” Reflecting on the building’s loss, he reminded Seattleites of the intense nostalgia many of them felt for the old homesteads and hearths of their youth left behind by the move westward. We become understandably attached to certain things — the old grandfather clock, the oaken bucket, grandpa’s armchair, the Weekly’s writer suggested. But, when “the time arrives — and come it will for all — when the link between the past and future must be broken; when the grown members of the family circle start out on life’s journey for themselves.” In other words, the writer let the readers down gently: Sentimentality is understandable, but the forces of change that brought you here are still at work.

The loss of the cabin, which was knocked down and shortly replaced by a two-story commercial structure fitting for a thriving frontier port, was a sign of progress. It had long been rendered secondary or obsolete as a public space — in 1859, Yesler had built a larger civic meeting space, Yesler Hall. The building that was built on the Cookhouse site became part of a city that thrived during the next quarter century until fire swept through the commercial district in 1889. Had it not been demolished, the log cabin Cookhouse would have perished then.

The fire created a chance to reboot the city almost from scratch, and today the modern neighborhood that grew in its place has become revered as historic Pioneer Square. That might give us nostalgists some hope.

Seattle has seen, and will see, more change. We’re a city of immigrants and change-agents, then and now. But unlike the old days, we now have 165 years of civic memory. We seek to preserve and protect what feels a part of the collective “us,” but we can also find hope — a kind of long-term silver lining — that the best of what is new might eventually become old and revered. Change is inevitable, but so also is preservation now in a city where we no longer leave our dead behind.