Gerrymandering. Literally and figuratively, there’s perhaps no uglier word in politics.

As a Democratic-leaning political consultant who studies voting patterns, I hear a lot about gerrymandering. From losses in state legislatures, to “skewed” congressional results, to even the Electoral College itself, the “g-word” has become a curse in lefty parlance.

To be clear, gerrymandering, the manipulation of political boundaries for partisan gain, is unpopular across party lines. It’s also a legitimate problem. With little counterincentive, state legislatures and other partisan entities across America do draw districts according to partisan designs. They’re only occasionally struck down by courts.

Still, there’s something that’s contributing even more to political polarization in America, and particularly here in Washington. And that something is us.

Welcome to The Big Sort. Introduced in Bill Bishop’s 2008 book of the same name, “the Big Sort” describes the emerging tendency of Americans to sort themselves “geographically, economically, and politically into like-minded communities” over approximately the last four decades. While Bishop’s work has generated heated debates – including around whether this sorting is self-selected, or a byproduct of social and economic changes – one claim hasn’t: The Big Sort keeps getting worse.

How we got here

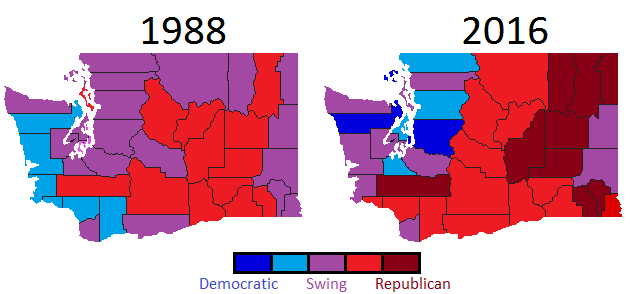

Before we explore the accelerating trend of the last few years, let’s start at the high level. Below we have the results of two Presidential elections in Washington state: on the left, Michael Dukakis’ narrow 1988 win; and on the right, Hillary Clinton’s 2016 landslide.

The map on the right sure doesn’t look like a landslide compared to the left-hand map. But Clinton’s win was over 13 points larger than Dukakis’s squeaker. The county map is deceiving because, by 2016, the once widely-distributed Democratic base has become intensely concentrated around the Puget Sound. In 1988, counties along the Sound voted for Dukakis by four points and the rest of the state voted Bush by five points, for a gap of nine points. By 2016, the Sound was voting Democratic by 30 points and the rest of the state Republican by 13 points.

In only six elections, the partisan gap between the Sound and the rest of Washington has ballooned from nine points to 43 points.

Wasted votes

For many, this is a familiar story: the Sound is getting bluer, while the rest of the state drifts red. Why, then, is this a problem for the Democrats? The “Big Sort” just means Democrats are “self-gerrymandering” into the Puget Sound. That’s the growth area of the state – shouldn’t Democrats be happy?

No, they shouldn’t. By “self-gerrymandering” through the Big Sorts, Democrats are increasingly living in homogenous communities and wasting their votes.

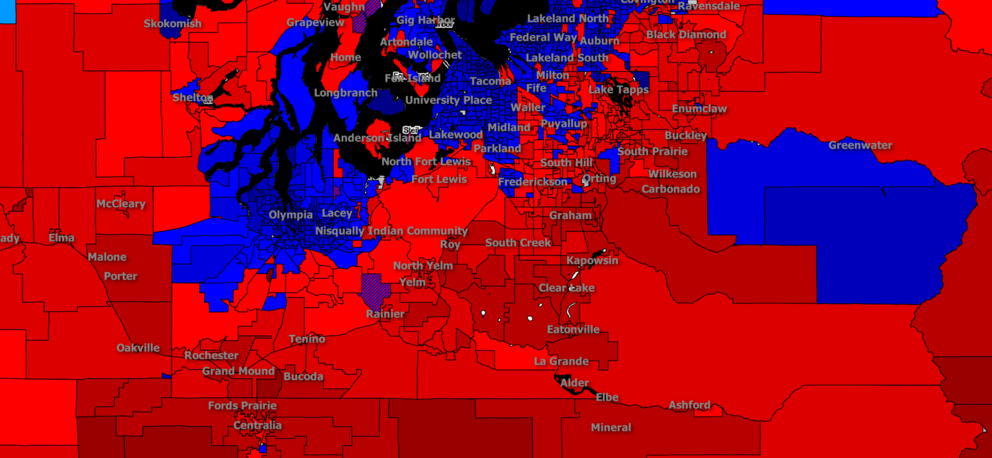

Both of these points require a bit of explanation. Let’s begin with homogeneity. By increasingly packing themselves into well-educated urban and suburban areas, Democrats are living among the politically like-minded at record-high rates. In 2016, the average Hillary Clinton voter in Washington State lived in a voting precinct where their co-partisans outnumbered Trump voters by nearly two-to-one. The average Trump voter, by contrast, lived in a precinct with an even number of Clinton and Trump supporters. While nearly a third of Clinton voters (31%) live in a precinct where they outnumber Trump supporters by more than three-to-one, barely any Trump voters (5 percent) live among the same homogeneity.

This may surprise some, who see Eastern Washington conservatism as the counterpart to Seattle liberalism. But Seattle voted Democratic by 84 percent this year. Outside of a few farming areas, nowhere in Eastern Washington is that uniformly Republican. Not even one-in-1,000 Trump voters in Washington live in an area as Republican as Seattle is Democratic.

Washington Democrats, not Republicans, are isolating themselves politically.

That leads to the next point: Democrats are wasting a ton of votes in uncompetitive districts.

Let’s explore this point by looking at our state legislature. The lopsided margins in Seattle and its suburbs mean that Washington Democrats have a stranglehold on many of Washington’s 49 legislative seats. In 2016, 16 of Washington’s 49 legislative seats – about a third – had about twice as many Clinton voters as Trump voters. Several had margins of around 10-to-1 or more. By contrast, only one legislative district was similarly skewed toward Trump.

What does that mean? It means Washington Democrats are inefficiently distributed. They’re much more likely to live in uncompetitive legislative districts than their Republican counterparts. The Big Sort has packed Democratic votes in areas where they’re superfluous. Trump voters, by contrast, are relatively more likely to live in swing areas. While they are fewer in Washington, they are disproportionately represented in key legislative seats.

This matters. The Washington Republican Party does a good job at winning tough legislative seats, but they would not control the State Senate without the Big Sort.

Recall that the average Trump voter lives in a voting precinct with about as many Clinton voters as Trump voters, while the average Clinton voter lives in about a 2-to-1 Clinton precinct. Trump voters are more likely to live in swing districts, and less likely to live in uncompetitive districts, than Clinton voters. Of course, this more efficient distribution of Republican presidential votes correlates to a more efficient distribution of Republican legislative votes. A Republican voter for President, after all, is likely to vote Republican on the local level as well.

The Big Sort, not gerrymandering, has given Republicans a leg-up in our local elections.

Big Sort, Big Consequences

Before I close, I want to note a few points I am not arguing. I am not arguing that urban Democrats all share the same political views. They don’t. I am not arguing that Democrats must return to being a party of the ‘non-cosmopolitan’ working-class. They haven’t been in years. And I am certainly not arguing that political trends are inevitable, continual, or predictable. We all know better.

What I am arguing is pure, cold, and mathematical. I’m arguing that the Big Sort has big consequences. By increasingly relying on constituent groups who are tightly packed into certain areas, Democrats are at a structural disadvantage. In Washington, this structural disadvantage has widened in every consecutive year since 1996. With a President-Elect Trump, it is hard to imagine the gap between the urban Puget Sound and “other Washington” will close much in coming years.

This problem isn’t fatal. A structural disadvantage doesn’t mean a guaranteed loss, and long-term demographic changes do appear favorable for the Democrats. Still, wise Democrats will spend the coming years speaking less of gerrymandering, and more of building coalitions. In left-leaning halls of conversation, it’s time to consider voters far afield of our corner of the Big Sort – voters that, year by year, have very literally gotten farther and farther away.