In conversation with the novelist Aleksandar Hemon, Nigerian-American writer and photographer Teju Cole writes of transatlantic identity:

...Nigeria haunts me in terms of being a space of unfinished histories. But my identity maps onto other things: being a Lagosian (which is like a city-state), being a West African, being African, being a part of the Black Atlantic. I identify strongly with the historical network that connects New York, New Orleans, Rio de Janeiro and Lagos.

When Hemon asks Cole to clarify the significance of these particular cities, Cole’s response is curt and deliberate: The four cities were “nodes in the transatlantic slave trade and in black life in the century following. They are the vertices of a sinister quadrilateral.”

It is not my place to explain how this quadrilateral shaped and still shapes black identity, nor is that my purpose here. (If you want a good introduction to the Black Atlantic, King's College’s Paul Gilroy quite literally wrote the book on it in 1995.) But if you’ll permit a generalization: If we accept the transatlantic slave trade’s darkly catalytic role in shaping the Black Atlantic, then we can also begin to understand a certain transpacific identity of the oppressed — one spurred by colonialism, militarism and imperialism in the centuries that followed.

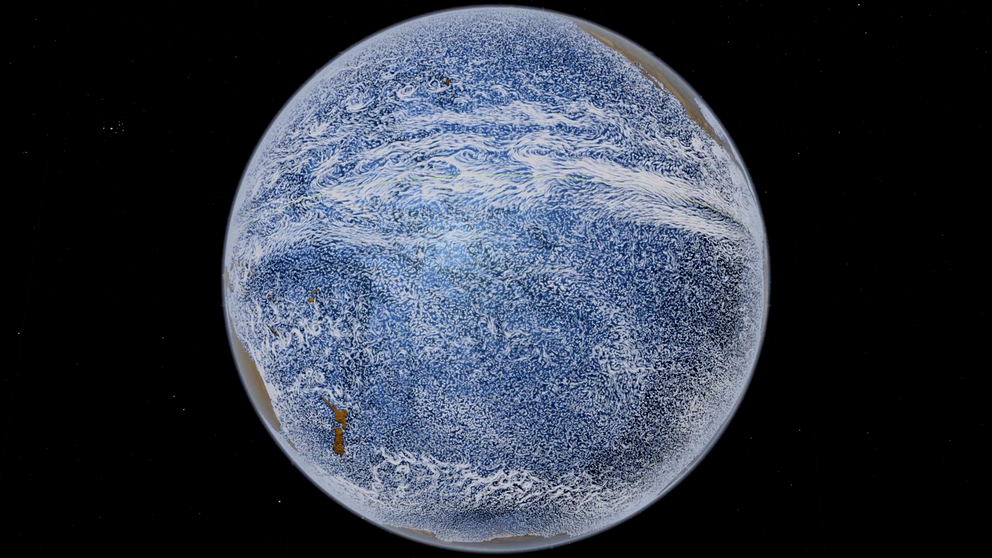

This identity is currently on display at the Wing Luke Museum in Seattle. Crammed into a tiny upstairs galley, We Are the Ocean — an audiovisual exhibit subtitled An Indigenous Response to Climate Change — offers a small but resonant forum for the voices suppressed by apathetic Western diplomats and technocrats. Listen, they say: The climate conversation is personal here. In the Pacific, climate change isn’t about polar bears. It’s about degradation and preservation, oppression and resilience. Accordingly, the climate theme is only loosely draped over the exhibit. More apparent is an aching transpacific solidarity.

We Are the Ocean is populated with a modest selection of sculptural, graphic and video installations, but it largely consists of recorded narratives and printed poetry. Pick up a conch-like shell and listen to the piped-in audio. Read the writing on the walls. Historically speaking, indigenous populations of the Pacific — from Hawai’i to Samoa, Guam to Alaska — bear the worst effects of a changing climate but have contributed the least in terms of carbon emissions. And now the seas are rising. The upstairs gallery at the Wing Luke is an oxygen tank for drowning stories.

Because of the inching, titanic nature of a changing climate, these stories are necessarily intergenerational. “Hear their words as they speak about the legacy we are leaving for our children,” writes Victoria University of Wellington professor Teresia Teaiwa in her introductory wall text. Hear “the ways we are building a world for those after us.”

And you do hear these words. A highlight of We Are the Ocean is poet Selena Velasco’s piece “You Come From.” The poem is a message to Velasco’s son Elijah. The lines are sweeping and visceral: “You come from sacred islands. / You come from suruhånus, palm leaf weavers, healers’ / hands massaging away intergenerational pain.” You come from sacred islands, writes Velasco, but these islands are disappearing — one more erasure of the indigenous Pacific, this one starkly physical.

And what of this intergenerational pain? When I spoke with Velasco at the show’s opening, she told me that one of her greatest concerns was that Elijah “might not have the chance to experience Guam,” where Velasco spent her childhood. Some of that concern was rooted in climate, but much was rooted in policy and economics. Yes, as the climate warms, the pain will continue to trickle down the intergenerational ice sheets, but as Velasco reminds us, it stretches backward, too. The pain has already been with her family for centuries — for reasons that have very little to do with climate change.

Not that pain precludes hope. At We Are the Ocean, watch the colonial spirit haunt a transoceanic identity, but pay attention as Pacific solidarity seeks to exorcise this ghost. Listen as whiteness laps at these shores, but mark the moments when indigenous resilience adapts and reclaims as many narratives as possible. The audience’s responsibility here is memorial in nature, but it is also elevating. Teju Cole again, writing to Hemon:

Cole: Like you, I am now in a country where people (convinced of their innocence) sleep well; and like you, I’m still one of history’s amnesiacs.

Hemon: Amnesiacs?

Cole: I meant to write “insomniacs”! But the error is illuminating.

Even the most progressive among us are capable of selective amnesia; of sleeping soundly through a tropical storm. We Are the Ocean offers the opportunity to rouse ourselves; to wake up and remember. Where the word-association game of today allows history to persist and begets “slave trade” from “transatlantic,” it fails across the other ocean, where “transpacific” now suggests “partnership.” Those in the indigenous Pacific don’t have the option of forgetting. The partnership these voices describe is different.

And partnership is where resistance can and must come from. On January 20, 2017, the United States will inaugurate a real estate developer to the presidency. He will be the only contemporary world leader to deny the reality of climate change. That this privileged blindness is somehow more explicit than the forms oppression usually takes shouldn’t matter. We Are the Ocean reminds the audience that the president-elect’s denial is simply the latest realization of the power dynamics that have infected the region for centuries.

These power dynamics beg solidarity. We owe it to one another to listen. Climate injustice remains the same difficult story to tell and the same difficult story to hear — but ultimately, it isn’t a tired one. It is one of urgency.

We Are the Ocean is on display through November 12 at the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience.