Maybe’s it’s an “only in Seattle” type of story, but for years citizen activists have been trying to get the state to preserve a small chunk of an old highway interchange in a park — a place it never should have been in the first place.

The so-called “ramps to nowhere," standing incongruously in the Washington Park Arboretum, are part of an incomplete expressway system that was stopped by citizen activists in the early 1970s in a seminal Seattle fight. But now, with the Arboretum undergoing a makeover and the ramps being removed, activists want a remnant of the old overpasses preserved to commemorate their battle — a kind of trophy for standing up to City Hall and the highway lobby.

And City Hall, which has long since come around to skepticism about any reshaping of Seattle to accommodate cars, might now agree. City Councilmember Debora Juarez will introduce a resolution on Oct. 10, asking the Washington Department of Transportation to transfer ownership of a small part of one of the ramps to the city so it can be left standing to commemorate local activism.

WSDOT has been planning to demolish all of the ramps as part of the Highway 520 expansion, which includes restoring and improving parts of the Arboretum. Originally, the stewards of the Arboretum approved a plan for complete removal of the old ramps. However, a group of landscape architects, artists, Arboretum advocates and others have argued that removing them would erase the visible legacy of the people of Seattle's rejection of a highway-centric view of the city back in the late 1960s and early ’70s.

A group called ARCH — Seattle Activists Remembered Celebrated and Honored — has been leading the effort. In 2014, there was an agreement about saving some ramp rubble for a possible memorial; however, saving an unfinished, elevated freeway portion is arguably a much more powerful symbol.

The draft of the city council resolution says the portion of ramp to be preserved is in recognition of “the importance in city history of the citizen revolt against the [R. H. Thomson] Expressway and how the efforts of civically engaged Seattleites saved many neighborhoods, hundreds of city blocks, and thousands of homes from the harmful impacts of highway construction.”

For half a century the ramps have been a curious and, for some, beloved feature of the Arboretum. Built in the 1960s during the construction of the original Highway 520 floating bridge, the ramps were meant to connect to an expanded expressway system that would ring the city, running south through Montlake, Madison Valley, the Central District and Rainier Valley, and north through Ravenna, Wedgwood and Lake City. Parts of the system would also cut through South Lake Union and Pioneer Square.

Rather than shape the city around mass transit, this vision would have turned Seattle into a freeway-dependent metropolis in the Los Angeles model. The part that was to run through the Arboretum was originally called the Empire Expressway, and later the R.H. Thomson, named for the city engineer who did so much to reshape Seattle’s landscape, including washing away Denny Hill.

In the late 1960s, a coalition of opponents from many of the impacted neighborhoods, students and faculty at the University of Washington, the Black Panthers and environmental groups formed a united grassroots effort to oppose the project. Opponents ranged from Saul Alinsky-inspired organizers to sci-fi writer Frank Herbert (the "Dune" series), then an environmental reporter. They crossed race, class and ideological lines and included Maynard Arsove, a University of Washington faculty member and civic activist; Aaron Dixon of the Black Panthers and later a U.S. Senate candidate and author; Margaret Cary Tunks of Citizens Against Freeways; King County Councilmember Larry Gossett, then an activist at the UW; Alfred J. Schweppe, who was an attorney; and architect Victor Steinbrueck.

The fight was a battle royal. Arsove, head of Citizens Against R. H. Thomson (CARHT), once described the opposition to the expressway system as a battle against “concrete dragons” and pleaded for a mass transit system. (The region’s voters rejected mass transit, too, in that era.) For those wanting to get the flavor of the anti-freeway fight, a documentary by filmmaker Minda Martin is in the works (the trailer can be viewed here). The project was not halted until protesters blocked the bulldozers.

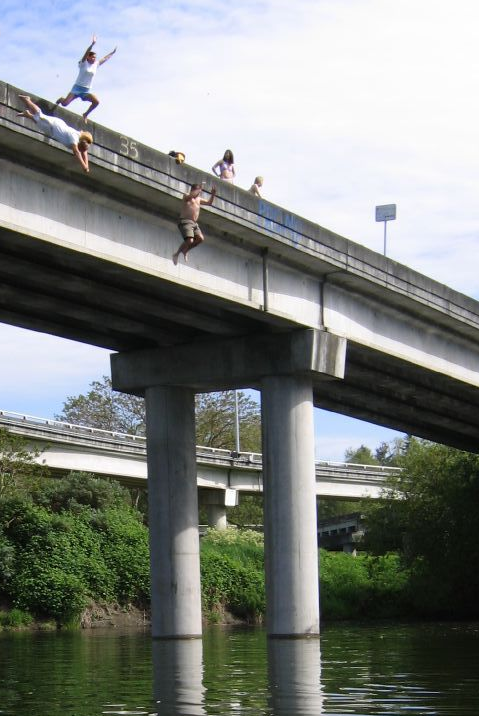

Eventually, the voters and City Hall had a change of heart and the R. H Thomson was dropped in the early 1970s. The result was unfinished ramps and overpasses that connected to nothing. They became weird ruins familiar to many swimmers who loved to jump from them, and to kayakers and canoeists who navigated the eerie labyrinth of pillars extending into Lake Washington. They had the feeling of ruins left from an ancient civilization, which, in effect, they were: a time before environmentalism.

The section proposed for preservation is a single support pier called Bent 6E, which includes four concrete columns and the beam they support. It is located in the North Entry portion of the park. The resolution proposes the columns be “preserved in perpetuity as a cultural artifact … as a reminder to future citizens of the power of participation in our democracy.”

The project has the support of a majority of the Arboretum and Botanical Garden Committee (ABGC), who say they were “impressed and enthusiastic” about the plan. The idea of retaining part of the ramps was endorsed by the Seattle Design Commission. The council resolution proposes funding for an engineering study, including a seismic analysis and recommendations for retrofitting the structure in order to make the feature safe and permanent.

Some opponents believe the ramps have no place in the park and that the makeover of the Arboretum necessitates their destruction. Michael Shiosaki of the city Parks and Recreation Department has previously voiced opposition.

Many of the advocates include survivors of the anti-expressway groups, and landscape architects like the University of Washington’s Iain Robertson, who is also member of the ABGC. He says there is a long tradition of keeping ruins — real or faux — in gardens and parks and that the ramps make the “Arboretum a richer place in terms of cultural experience.”

What were once eyesores have become imbued with meaning, and timely in an era of revived citizen activism in Seattle. From causes like Black Lives Matter and Block the Bunker to stopping coal trains, Arctic rigs and oil pipelines, activists poke our conscience and help us reconsider our basic assumptions. The standing ramp columns, like Roman ruins, are a reminder that conventional wisdom isn’t always wisdom. We’d be wise to remember that.