A glimmering, 30-story high-rise in downtown Seattle, Escala is perhaps best known as the home of Christian Grey, the sadomasochistic billionaire at the center of E.L. James’ novel, “50 Shades of Grey.” But this summer, it’s gained a reputation for something else: a high-profile legal fight between the owners of the building’s luxury condos and the city’s zoning department, which could block legislation that would create more affordable housing.

I visited the building recently to speak with resident John Sosnowy, a retired investment manager from Texas who is leading the fight against the city. For “50 Shades” readers expecting an atmosphere of elegant eroticism, the lobby may come as a shock. Like a scene out of 1980s Las Vegas, there are vases covered in gold faux-Egyptian ornamentation, brightly patterned carpets, and a fireplace that always seems to be burning. There’s a knock-off of glass artist Chihuly’s work hanging from the ceiling. A zebra-striped couch wouldn’t seem entirely out of place.

Sosnowy and I sat in one of Escala’s empty community spaces, where he broke down why the group he unofficially leads — the Downtown Residents Alliance (DRA) — isn’t Exhibit A for the selfishness of affluent homeowners in Seattle, as some have claimed.

Do all the active members of DRA own expensive condos? Well, yes, he admitted: They include the past president of Starbucks, Howard Behar, and Expedia executive Greg Mushen. Could the legal battle they’ve launched against the city lead to a reduced amount of affordable housing, by delaying the ability of City Council to pass laws requiring it from developers? He reluctantly said it could. When pressed, he also admitted the changes DRA are demanding would help protect property values at Escala, which runs contrary to what he told the Seattle Times in June.

“I’d be happy for them (the city) to get all the money for affordable housing, as long as it’s not at the expense of screwing up the future of downtown,” said Sosnowy, 74.

But the DRA’s fight isn’t the standard one about views, unless you count the buildings that surround Escala — the Westin hotel and Bed Bath and Beyond — as scenic. And for those seeking a narrative of comfortable homeowners fighting affordable housing policy, that's true, but not the full story. In fact, when it comes to their concerns, the group may have a point.

--

The story of the Downtown Residents Alliance and its legal battle with the city is one in which no one looks particularly good. Not the city or its councilmembers, some of whom allegedly made private promises to the wealthy condo owners in DRA. Certainly not the condo owners.

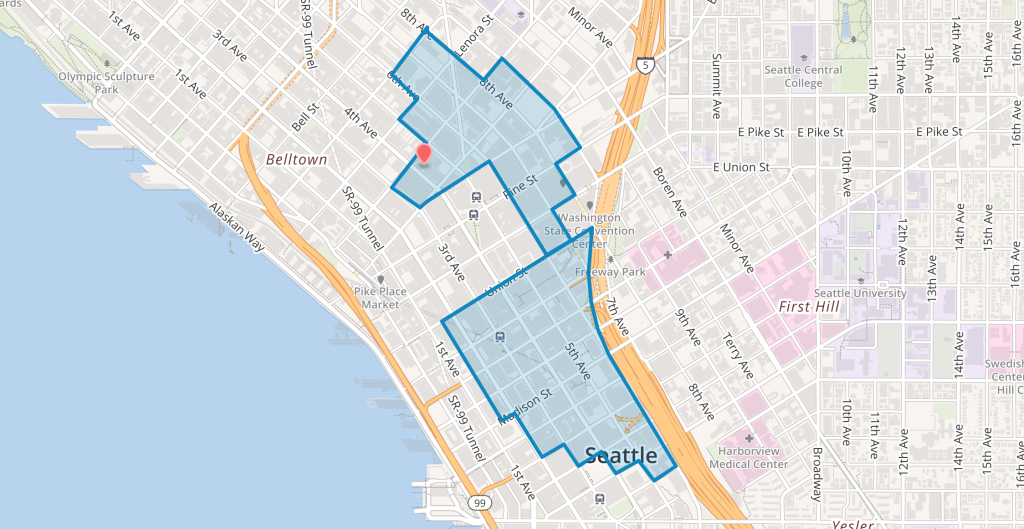

To understand it, one must know a few things about downtown zoning. Namely, there are different zones of downtown Seattle, with different rules for what you can build in them. The two-and-a-half block zone in which Escala is located is called Downtown Office Corridor 2 (DOC2). It has rules meant to encourage office buildings and dense commercial activity, which means that it allows buildings to be packed very tightly together.

But it doesn’t forbid residential buildings, such as Escala. According to Dennis Meier, strategic adviser with the Seattle Department of Planning and Development, “the feeling has been that mixing uses is a good thing (in DOC zones). It helps introduce activity at different times during the day, instead of having them clear out at night, which makes areas more lively and safer.”

Sosnowy thinks this is a big mistake. Escala, he says, “never should’ve been allowed to be built” in a zone that allows such tight spacing. This is because there is now a proposal for another residential high-rise directly across the alley from it, by New York-based Douglaston Development. At 45 stories high, it would tower over 30-story Escala, and stand a mere 22 feet away.

The Douglaston project is already well on its way through the approval process, and there’s not much the residents of Escala can do about it at this point (although they vow to fight to the bitter end). In all likelihood, Escala’s inhabitants will eventually face a wall of glass and steel, potentially giving them floor-to-ceiling views of their neighbor’s living rooms, and vice versa.

What’s more, there are properties all around Escala that are open to such development. If all are snatched up, Escala could become a shadowy, boxed-in skyscraper, dwarfed by the taller buildings all around it. At full buildout, the area might look like the claustrophobic skyscraper canyons of Houston or Dubai.

Thus the DRA’s appeal, which claims the city didn’t conduct due diligence before issuing a State Environmental Policy Act ruling in May. This ruling stated that zoning changes would not have any notable adverse impact on downtown’s livability or environment.

“(City planners) simply decided there wouldn’t be any significant impacts downtown from this without studying it,” says Claudia Newman, one of the attorneys representing DRA. But “there’s a process that has to occur under state law, which requires the city to determine whether there’ll be significant environmental impact from this sort of action.”

The DRA lobbied the Seattle City Council last year to do an environmental impact study, and in response, Sosnowy says six city councilmembers promised to request increased tower spacing requirements in DOC2. Four of them — Sally Bagshaw, Jean Godden, Nick Licata, and Tom Rasmussen — signed a letter to the mayor, asking him to put the city’s planning department to the task. Tim Burgess and Bruce Harrell were “promises” that didn’t come through, Sosnowy says. In an email, Burgess denies making any promises to the group. Harrell has not responded to requests for comment.

When no new spacing requirements emerged, the DRA appealed the Seattle planning department’s ruling. And that’s when things went from legitimate lobbying, to downtown condo owners holding affordable housing policy ransom.

--

Like much of Seattle’s current battle over zoning, the details of the DRA’s appeal are wonky, but could have an impact lasting generations.

If successful, the appeal would essentially require the city to conduct an environmental impact review downtown, gauging the impact of additional high-density development on issues such as downtown’s light, traffic and open spaces. That study could take a while, and slow down Mayor Ed Murray’s affordable housing proposals — specifically, his efforts to require developers to include affordable housing in new projects or pay for it to be built elsewhere, a policy called Mandatory Housing Affordability.

Which is exactly the DRA’s point. “The mayor’s up (for re-election) next year,” Sosnowy told me. “I think he’s well-meaning on affordable housing, but he’s trying to rush it. He wants to hang a chit up there for his reelection. I think there’s a middle ground here we need to find.”

However, for those who believe Seattle is behind the curve on requiring developers to contribute to the affordable housing supply, there is a greater sense of urgency, and anger toward DRA. After all, the appeal essentially blocks the City Council from voting on Mandatory Housing Affordability legislation.

Meier of the city planning department said that downtown’s zoning standards, which were created in 2006, were the subject of widespread debate. There were discussions of whether to include residential spacing requirements in DOC2, he said, and it was decided this would impede the zone’s primary goal. With more spacing, there may be more residential development than dense commercial development in downtown, the city reasoned.

According to Peter Steinbrueck — who was chair of the City Council’s Urban Development and Planning Committee in 2006, and currently serves as a paid consultant for DRA — the desire to keep spacing requirements out of DOC2 came from developers. He says he opposed this move then, and now continues to do so through his work with DRA.

But because developers oppose these spacing requirements, inserting them into the city’s housing proposals could throw into disarray the carefully calibrated “grand bargain” Seattle policymakers reached with the real estate industry regarding affordable housing funding.

What’s more, there’s something disingenuous about the DRA’s messaging around their actions. Sosnowy has claimed that the fight has nothing to do with Escala, since Douglaston’s tower is already well on its way toward final approval.

“This is about the future of downtown Seattle, it’s not about us at all,” Sosnowy told the Seattle Times in June. “We can’t do anything about our block. We’re saying, ‘Don’t do it to the next guy.’”

But the truth is that Escala is something of a special case. According to Meier, very few properties could be affected the by a lack of spacing requirements — around 10 sounded right, or potentially less. Many of them are around Escala, which could ultimately be boxed in on three sides.

I pointed out to Sosnowy that the Urban Yoga Spa directly next to Escala could get torn down to make way for high-rise. That would hurt the property values of his condo building. Given that, how can he claim it’s only about the “next guy?”

He shrugged. “Well, people are saying this is just for us,” he said. “It’s not just for us.”

Sosnowy complains that Murray and councilmembers have treated his group as just a minor annoyance, another group of community members to placate as their requests are written off. But that reputation may soon change. The DRA’s case will go before a hearing examiner on September 7, and a decision could follow soon thereafter.