As I entered the Temple of Justice last week for the latest Supreme Court hearing on the McCleary lawsuit, I pondered a question that has troubled me and members of my organization, the Washington Association of School Administrators, throughout the course of the lawsuit: What will happen to education funding after the Court relinquishes its jurisdiction in the case?

Nothing I heard in the state’s testimony that morning provided any sense of relief regarding that concern. As with the 2014 hearing — when Washington policymakers were held in contempt for failing to fully fund K-12 education — the state continued to exaggerate past accomplishments, minimize the scale of what remains to be done, and over-estimate legislative commitment to creating the funding system required by the state constitution.

At some point, though, whether or not the solution is complete, the court will relinquish its jurisdiction. And given past behavior by our Legislature, that’s cause for concern.

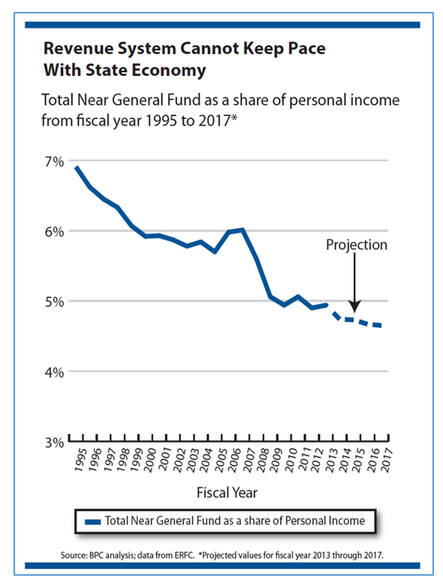

During the past four decades, a big part of why Washington’s education funding system went from near the top among the states to near the bottom is the powerful pressure exerted on the legislature by anti-tax forces. This isn’t just an opposition to new taxes. As the attached graph from the Washington State Budget and Policy Center shows, we’re nowhere near the level of state revenue as a percent of personal income that we were two decades ago.

In a 2014 presentation on this topic, David Schumacher, director for the state’s Office of Financial Management, said this decline represented a loss of $15 billion in revenue for the biennium. That would be more than enough to address the state’s education funding shortfall.

Some of the state revenue decline is due to a tax system that is overly dependent on sales tax, which is a declining revenue source. Much of it, however, can be traced to the pressure anti-tax forces have exerted on our legislators.

One response to this pressure is the Legislature’s inclination to provide an increasing number of tax breaks. The number of exemptions has grown significantly as our state revenues have simultaneously declined.

According to a 2016 report by the Washington Department of Revenue, the estimated net value of these exemptions, if repealed, is $30.1 billion for the 2017-19 biennium. That represents 92 percent of the projected $32.6 billion in revenue that would be generated by these state tax sources.

According to a 2016 report by the Washington Department of Revenue, the estimated net value of these exemptions, if repealed, is $30.1 billion for the 2017-19 biennium. That represents 92 percent of the projected $32.6 billion in revenue that would be generated by these state tax sources.

In other words, the Legislature has given away nearly half of the potential revenue from these sources. A fraction of these tax-break resources would be enough for the state to fully fund basic education.

The net effect of this downward pressure can be seen in “Quality Counts,” a compilation of state-level education data gathered by Education Week. The “Quality Counts” information adjusts the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) data to reflect cost-of-living differences between the states. That method provides relevant context information related to the impact of education dollars.

The numbers reflect Washington’s ranking among the states in its per student funding for any given year. It’s worth noting that by 2005 Washington reached a low point of 45th in the nation using the Quality Counts data. The following year, as that ranking held steady, Gov. Chris Gregoire’s administration offered a 10-year plan for education, which did not include any new funding sources. McCleary v. State of Washington was filed the following year, in 2007.

Being ranked among the worst states in the nation for education was a long fall from being ranked 12th among states in1980, two years after the Washington Supreme Court affirmed the Doran decision. That landmark decision gave the state a much more primary role in funding our public schools. Given the trend since that decision, it appears to be a role legislators have been unable or unwilling to fulfill.

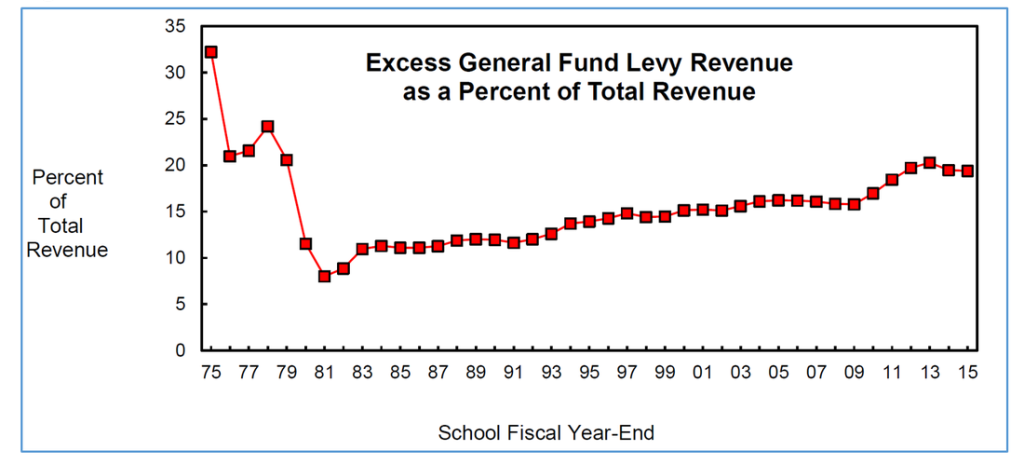

As the graph above demonstrates, local levy funding as a percent of total school revenue made a steep decline in 1978 following the Doran Decision, but that percentage began to steadily increase up to current levels in 1981.

To be clear, the steady increase didn’t occur because of any legal action that nullified Doran’s finding, which regarded the state’s responsibility to fully fund basic education. It happened because countless legislators over the past four decades found it more palatable to raise the levy lid than to raise the taxes necessary to fully fund our schools.

During that time, local voters in many communities have supported dramatic increases in their local school levies. As that local revenue source grew, many school districts increasingly used levy funds to cover the shortfall in state funding. Because of the wide disparity in property values, other districts weren't able to provide their students with similar support. That trend is what led to the McCleary decision.

As we near the end of this decade-long legal battle, I find myself wondering about the future. Winston Churchill once said, “When the situation was manageable it was neglected, and now that it is thoroughly out-of-hand, we apply too late the remedies which then might have effected a cure.” This seems pertinent, as does another saying from the former British prime minister: “Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

Hopefully, after the current legal proceedings have ended, Washington’s leaders will be committed to avoiding a repeat of this erosion in the constitutional principles clarified by the McCleary and Doran decisions. Unfortunately, hoping for that commitment doesn’t provide much confidence that the errors of the past won’t be repeated.

It will be up to the state’s next generation of leaders to remain vigilant so that every child realizes the promise of an amply funded education as guaranteed by our state constitution.