This is the first profile on the 7th Congressional District race. Read about Brady Walkinshaw here.

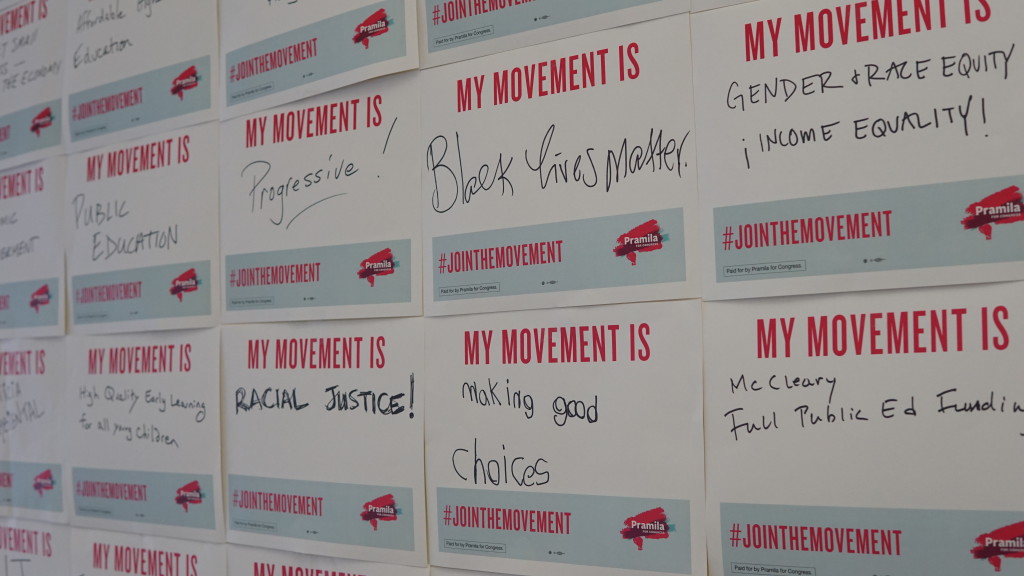

In her speech on primary election night, Pramila Jayapal had something for just about everyone in this left-leaning city. She talked about expanding the middle class, racial justice, environmental justice and the Black Lives Matter movement, women’s rights, immigration reform and forgiving college debt.

“So that it doesn’t matter whether you’re black or brown or what zip code you live in, you grow up with the ability to have a dream and work hard to make it come true,” she proclaimed to a packed house at the Palladium at Hale’s Brewery in Fremont.

Seattle is evolving and diversifying, new people are coming in with different experiences and backgrounds. Jayapal is doing something different as well. She’s running her 7th Congressional District campaign on a platform that hasn’t been common of Seattle politicians in the past, emphasizing racial justice and immigration reform.

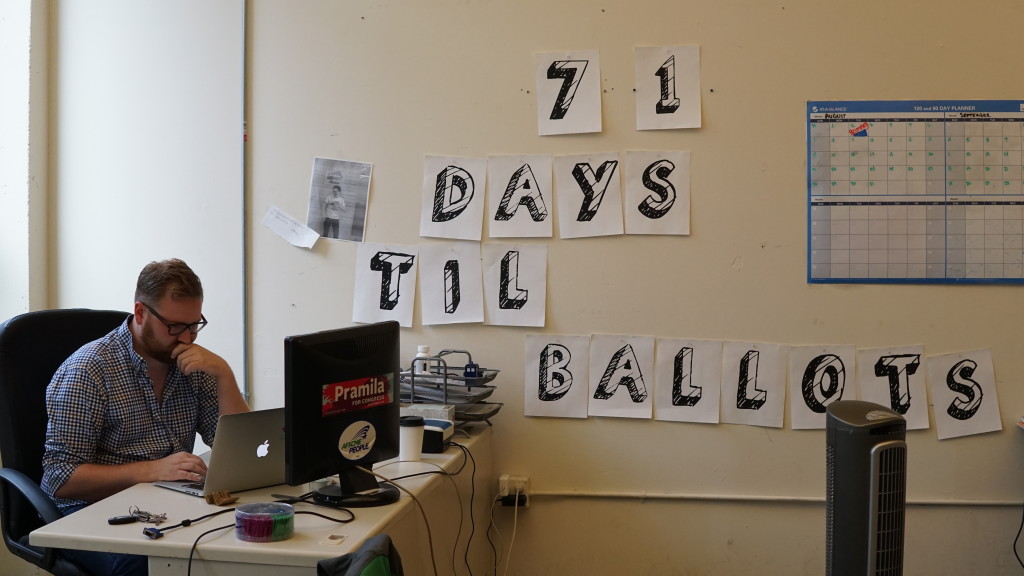

And it’s working: Jayapal won the August primary with 42 percent of the vote. Her closest competitor, Brady Piñero Walkinshaw — who also represents a fresh, diverse face in the race — received only half of that. Jayapal and Walkinshaw will face off in November.

Jayapal's message is catching on despite the fact that Seattle is 69.5 percent white, according to the most recent Census. The 7th Congressional District, where Jayapal is running for a seat, is 76 percent white. (The remaining 24 percent are, in descending order, Asian, Hispanic, African American and Native American.)

The crowd at Hale’s on primary election night defied easy description. There were plenty of white-haired Seattle liberals in attendance, but there were also many young people and people of color, all cheering for the triumphant Jayapal, herself an Indian immigrant.

Her campaign credited this diversity, and an aggressive ground game that sent hundreds of volunteers door-to-door, for the win. “During the last two-and-a-half weeks of the primary, we had a group of Somalis who were going out and knocking on doors of other Somalis in West Seattle,” says Aaron Bly, Jayapal’s campaign manager. “They are out there voting and engaging in a way they wouldn’t have before.”

A big part of that is because they’ve known Jayapal for decades through her work with an immigrant rights organization that she founded called OneAmerica. But those who have followed her career say that she is also a natural organizer. She’s been rallying people around issues for 25 years.

“I think what she has done well is to not create a silo of constituents,” says Nick Licata, a former Seattle City Councilmember, “but rather create a broad fishnet to collect as many different race, age and gender groups as possible with a common theme.”

It’s a theme that is playing out elsewhere in the country, too, as a class of political candidates ride a wave of progressive sentiment whipped up by Bernie Sanders. But Jayapal’s story is interesting in and of itself.

To understand Jayapal’s approach to politics, it helps to know her personal story. Jayapal grew up in India and Indonesia, but says her father had a fascination with sending his children to the United States. He believed it was a place of opportunity.

When Jayapal was 16, her parents used all of the $5,000 in their bank account to send her to the states, alone, to attend Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

“I didn’t appreciate that sacrifice fully until my son turned 16,” Jayapal says, “and I started to think about what it means to take all of your savings and send your kid across the ocean and know they might never come back.”

Her father never envisioned her becoming a politician (and she had no aspirations to become one). He was dead set on her becoming the CEO of IBM. It was the pinnacle of success.

“The three professions I was allowed to be were a doctor, lawyer or businessperson,” Jayapal says. Her family didn’t make a lot of money, so she could only call home once a year and send aerograms. She used her one call to tell her dad she had chosen to major in English literature instead of economics.

“I held the phone away while he screamed, ‘I did not send you to the United States to learn how to speak English! You already know how to speak English!’” she says. Eventually, Jayapal did a stint on Wall Street before getting a job with a company called Physio-Control, selling medical defibrillators .

“I was the first and only woman of color in Indiana and Ohio selling defibrillators to firefighters, and they had really different political views than me,” Jayapal says. "But I was the top salesperson because I listened."

It’s another skill people often mention when talking about Jayapal: She’s a listener.

“There was a model before of politicians being like, ‘You elect me and then I will go get it all done on my own, just trust me,’ and maybe that worked before, but I don’t think that’s the way,” Jayapal says. “What we have to do is reconnect government to regular people and in order to do that, you have to build a movement that is bigger than yourself.”

Jayapal's first lesson in movement building came after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001. She had moved to Seattle in 1990, and was involved with immigrant communities in the area. She began receiving calls about people being attacked for their skin color. She heard about hijabs being pulled, Sikh-American cab drivers and hotel owners facing attacks, and she took it as her cue to do something bigger.

Jayapal ended up organizing a press conference with U.S. Rep. Jim McDermott (whose seat she now hopes to fill) and Gov. Gary Locke to declare Washington a "hate-free state." That work gave rise to a nonprofit called Hate Free Zone. The group later took on the Bush administration for civil liberty abuses, most notably suing the government for the illegal deportation of Somalis, a case they ended up winning.

“After that, we realized it wasn’t just these post-9/11 communities — that’s how we referred to them — but immigrants in general needed more organizing and a collective voice,” Jayapal says.

Today, the group, which changed its name to OneAmerica in 2008, organizes people to advocate for policy change, develops leaders within immigrant communities, and furthers for immigration reform. And now, Jayapal’s advocacy work, and her identity as an immigrant herself, is helping to fuel her candidacy for Congress.

“People used to be very tied to the idea of politicians looking like them, working like them, acting like them,” says Cathy Allen, a local political consultant. “But the fact is that someone like Pramila is now the prototype for who many Democrats want to vote for.”

Licata sees it, too. “I really think her campaign and her possible election to Congress is part of a broader national trend," he says. "We are seeing immigrants come to the U.S. because they believe in our democracy, they embrace it fully and they want to participate in it."

Another case in point: In Minnesota, Ilhan Omar, a candidate with the Democratic Farmer Labor Party, won the primary election for a seat in the Minnesota State Legislature. If she wins the general election in November, she may be the first Muslim East African woman to hold elected office in the United States.

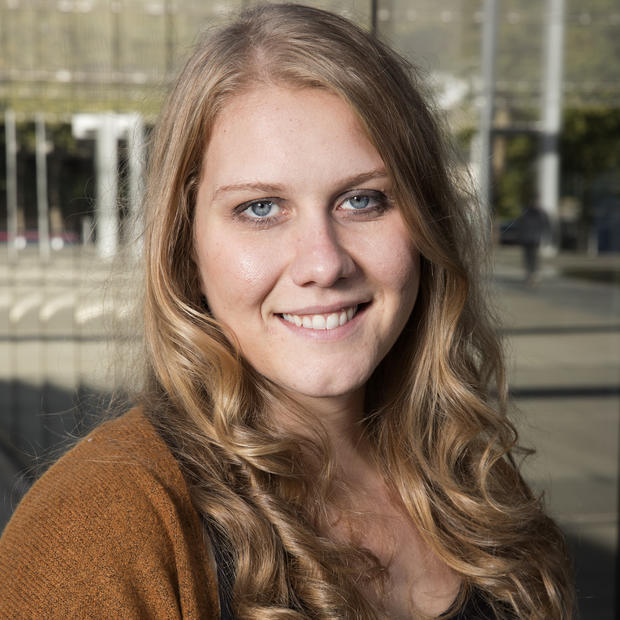

If Jayapal wins the general election, she would be the first Indian-American woman elected to Congress. Aneesa Shaikh, 19, says that’s a big part of why she is volunteering her time as a finance intern for Jayapal’s campaign.

“My dad is from India, so that’s very personal for me to have representation of people like me in Congress,” Shaikh says. “I think a lot of young people are behind her because she represents the things we care about in a way that enables us rather than speaks for us. She isn’t like, ‘OK, I get it, sit down.’ Instead, she supports us in having a tangible difference.”

It’s not a big surprise that Jayapal is appealing to a wide range of young Washington voters, when national trends seem to be moving that way too. According to Pew Research, 76 percent of millenials say immigrants strengthen the country, up from 59 percent in 2013. More than their parents and grandparents, they also tend to favor socialist-style policies such as those championed by Seattle City Councilwoman Kshama Sawant, who seems to enjoy a similar base of support to Jayapal’s, and Bernie Sanders, who endorsed Jayapal in April.

The importance of that youth vote cannot be underestimated either locally or nationally. An article in the Atlantic points out that when Bush won the presidency in 2000, few millennials could vote, but in 2016 they will constitute one-third of the voters. In 2000, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians constituted 20 percent of voters, but they’ll make up more than 30 percent in 2016.

Candidates running on progressive platforms are winning elsewhere, as well. Take Zephyr Teachout, running for the 19th New York Congressional seat, a rural swing district currently held by a Republican. She is up against John Faso, a Republican backed by big money, but she received substantially more votes in the August primary.

“I think people have always cared about progressive issues and we are beginning to show Democrats it’s the best way to win elections and get the biggest number of people behind them,” says Stephanie Taylor, co-founder of Progressive Change Campaign Committee. “What you’re seeing now are voters demanding Democrats get back to talking about economic issues voters care about.”

It’s a direct challenge to the recent Democratic Party orthodoxy, which holds that the best way to win elections is to lead from the political center. That may hold true elsewhere, but in left-leaning, diversifying, fast-changing Seattle, Jayapal’s pitch seems to have powerful appeal.

Whether she can stand up to Walkinshaw in a field that has narrowed from nine candidates to just two is another matter, but for now, Jayapal is upbeat.

“The energy in the room on the Primary night was amazing because people felt like it was their campaign and they had a win — and they did, because they helped make this happen,” she says. “That’s how you build a movement: You just keep making it bigger and bigger and bigger, and you keep bringing people into it.”

More reading: "How Brady Walkinshaw could pull a surprise win for Congress"