Doctors confirmed the eighth case of Zika in King County this week, bringing the total number of infections found in Washington State up to 24. Zika puts fetuses at risk of microcephaly, a condition that affect’s a baby’s head size, and thus brain development.

In all of these instances, the virus was acquired while traveling in Latin America or the Caribbean. But Zika is now spreading in Miami — the first cases of local transmission within the continental U.S. Does that mean that mosquitoes could spread the disease here in Seattle, too?

The short answer: “It’s pretty unlikely, at this point,” says Justin Roby, an immunologist at the University of Washington who specializes in flaviviruses (a genus of viruses that includes dengue, West Nile and Zika).

But don't breathe a sigh of relief just yet.

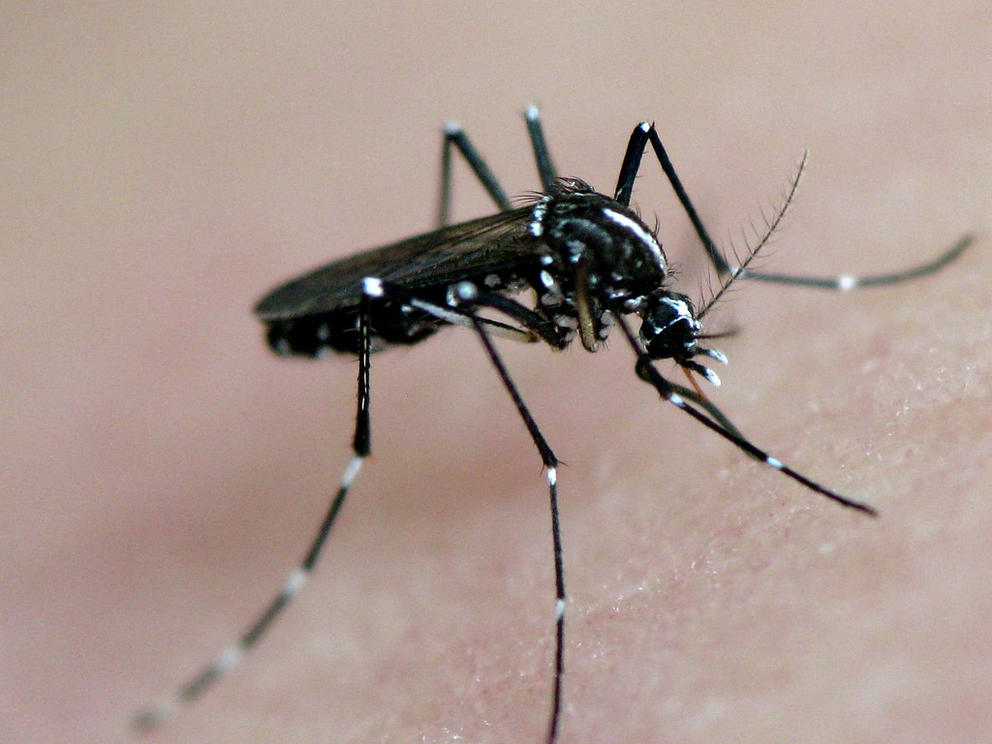

None of the more than 40 mosquito species found in Washington are effective carriers of this particular virus. Zika is most commonly transmitted by a species of mosquitoes called Aedis aegypti and, a bit less commonly, by another species called Aedes albopictus. Simply put, the weather here is too cold for those types of mosquitoes, which prefer the tropics. (In fact, for a variety of reasons, we have relatively few skeeters here at all.)

While the range of Zika-carrying mosquitoes, particularly albopictus, does include large portions of the U.S., from Delaware to California, and is increasing as climate change continues to cause temperatures to rise, at present, Washington is a safe distance from any of the bugs’ potential habitat.

“There may be rare instances where the mosquito is imported accidentally,” Roby explains — on a shipment of fruits or vegetables, for example. “But I don’t imagine they’ll be able to establish themselves here because of the winters we have.”

But unlike other flaviviruses, Zika can spread via means other than mosquitoes, and this is what’s keeping public health officials awake at night. “The issue for Seattle is really sexual transmission,” says Meagan Kay, an epidemiologist and regional health administrator for the King County Department of Public Health.

Translation: The virsus could still be transmitted here from partner to partner if one person contracted Zika while traveling to a region where aegypti and alobpictus mosquitoes carry the virus.

The discovery of sexual transmission is part of what has made Zika so alarming: “No one expects a virus to change its form of transmission so unexpectedly as this,” Roby says.

Which is why King County Public Health has spent about $200,000 and 1,900 hours of staff time so far this year to combat the disease.

Health officials have tested over 300 people for possible Zika infections, patients who had traveled or had a sexual partner who had traveled to an affected area and are pregnant and/or have at least two of the four symptoms associated with the virus: fever, rash, red eyes, and joint pain.

“We’ve had very few positives among those who have been tested,” Kay says. But there's still a lot we don't know.

The jury is still out on how long Zika stays in a person’s reproductive tissues, but research suggests it’s anywhere from one to 2.5 months. Health officials recommend that all women and men either abstain from sexual activity or use barrier protection for at least eight weeks after traveling to places where Zika is spreading. (Here's looking at you, Olympic athletes and super fans!)

“The main message that we’re trying to get out is that women who are pregnant or plan to become pregnant avoid travel to any of those areas where Zika could be transmitted, and that they should avoid sexual contact with somebody who has traveled to those areas while they’re pregnant,” says Kay. If they have to travel to an area where Zika could be transmitted, Kay suggests taking extra precautions to avoid mosquitos, such as wearing long sleeves and using DEET-based mosquito repellant.

King County has been providing guidance to health care providers on what to look out for and what sorts of precautions to advise to their own patients, but Kay worries that those in Seattle who would be most at risk are people who may not have access to specialized prenatal care.

“We want to make sure that all prenatal providers, not just obstetricians and gynecologists, but even family practioners and primary care providers, are really talking to patients about this illness and making sure that they counsel them appropriately and identifying people who may be infected,” says Kay.