Whenever something new is built in a city, something old is inevitably lost. Sometimes the tradeoff is clearly worthwhile, as when a parking lot or vacant commercial building is redeveloped. Other times the tradeoff is contentious. Should we, as a city, prefer six new townhomes to an old bungalow? Or a new 100-unit apartment building to a rundown but affordable eight-unit apartment?

These decisions point to the most fundamental challenges facing Seattle's future: how do we add enough new homes to address our housing shortage, while preserving existing communities, especially in low-income areas most vulnerable to displacement?

One way to analyze this tradeoff is through a simple metric: the number of new homes built for every existing home that is demolished. This metric is useful because it gets beyond the debate over the "right" amount of new construction, and gets closer to a cost/benefit analysis that everyone should agree on: whatever our overall rate of construction, we should prefer to build in a way that minimizes demolition and displacement.

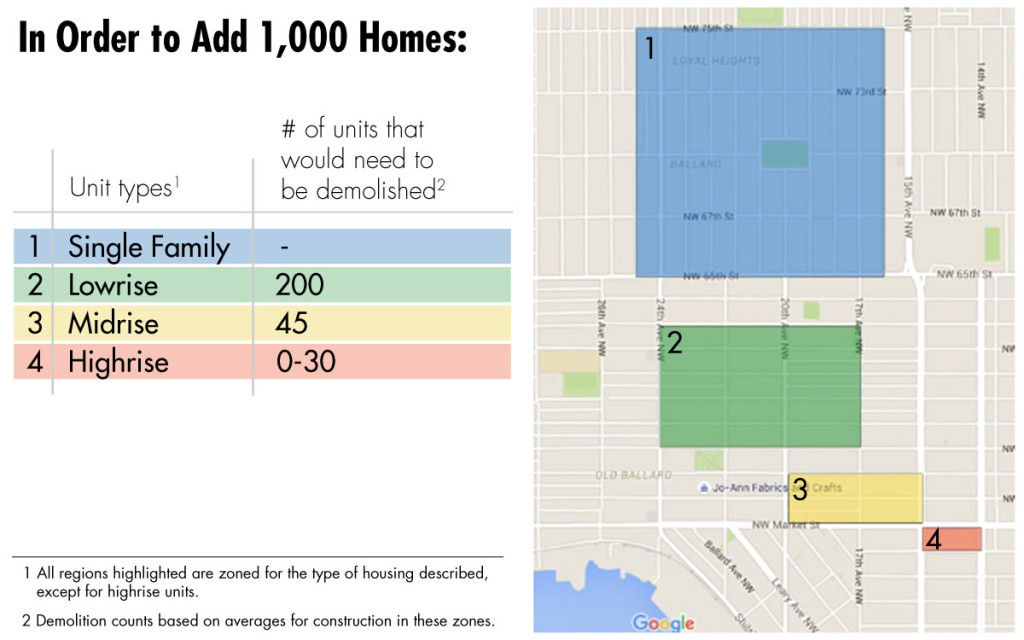

Using this metric, construction in areas zoned for higher density causes dramatically less demolition and displacement per unit built. That bigger buildings can house more people is perhaps an obvious point. But the consequences go counter to the arguments of some neighborhood preservationists and anti-displacement activists who oppose taller buildings — for example, a recent flyer promoting a University District community meeting warned that “our diverse mix of low cost housing, affordable shops, and businesses all would give way to steel and glass towers unless we stop it!”

If you accept that we need more housing — and with Seattle's population growing by 10,000 people a year, it's hard to argue that we don't — then the best way to minimize displacement and preserve older buildings is to concentrate that new housing in fewer, taller buildings.

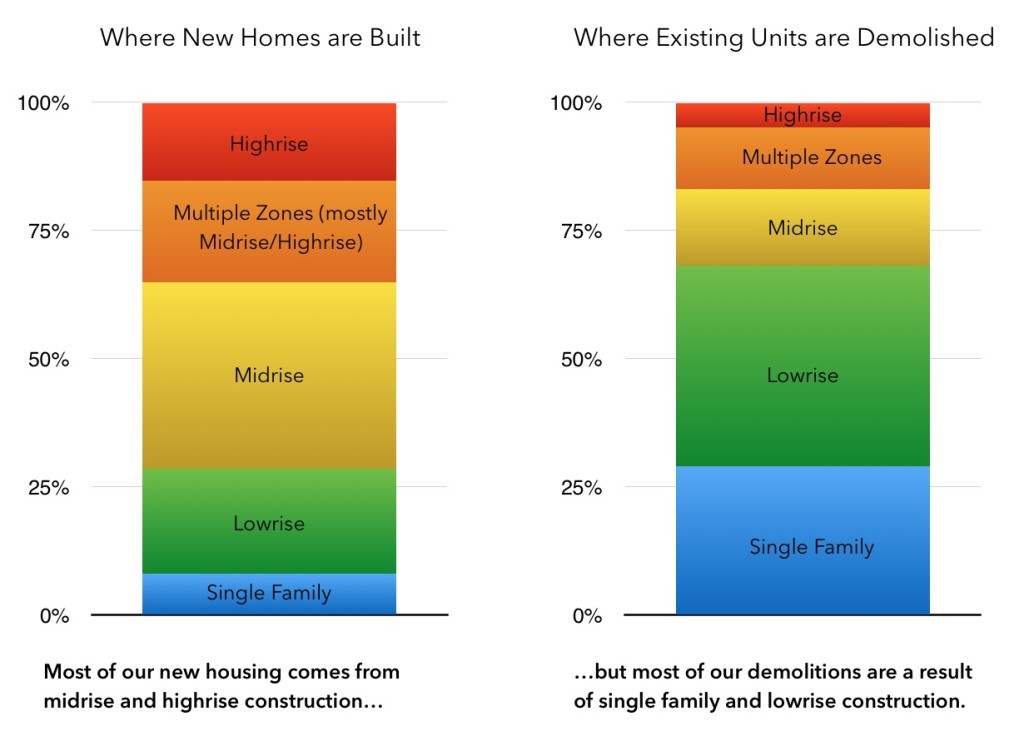

Over the last decade, the city has built about 5,000 new units of housing each year, while demolishing about 500 existing units. In other words, we build about 10 new homes for each existing home that's demolished. But that city-wide ratio hides vast differences on a local scale.

Over the last decade, the city has built about 5,000 new units of housing each year, while demolishing about 500 existing units. In other words, we build about 10 new homes for each existing home that's demolished. But that city-wide ratio hides vast differences on a local scale.

Consider the traditional neighborhood of detached single-family homes, for example. We tend to think of single-family zoned neighborhoods as fixed in time, since no denser housing can be built there. But in fact, a quarter of all units demolished in the city are in single-family zones. These are older, smaller homes being replaced by new, larger homes, resulting in no net increase in housing stock.

Single-family zoning is not the bulwark against demolitions and displacement that it is sometimes portrayed as. It does, however, ensure that these neighborhoods cannot contribute in any significant way to housing our growing population.

When it comes to density, the next level up are the city’s duplexes, townhouses and small apartments. This low-rise housing contributes significantly to our overall housing development, providing about 1,000 new units a year. And many of these are two- and three-bedroom family sized units, which are desperately needed, but seldom found in larger buildings.

Unfortunately, low-rise housing is also our single largest source of demolitions. Despite taking up less than 10% of Seattle land area, low-rise zones account for more than a third of all units demolished. The frequency of demolitions in these zones goes a long way towards explaining the pushback against expanding the amount of the city where this sort of construction is permitted.

Our densest housing types are mid-rise and high-rise construction, found in neighborhood commercial centers and downtown. We build about 3,400 units of high density housing each year, but remarkably, only demolish about 150 units to make way for this housing.

Put another way, mid-rise and high-rise construction produce more than double the amount of housing produced by townhome and single-family home construction, while accounting for half as many demolitions.

It's not just that denser forms of construction fit much more housing onto a given lot. Much of it also takes place without any residential displacement at all, as it’s often concentrated on land that was previously surface parking lots or small commercial uses.

Displacement caused by new construction does real damage to vulnerable people and communities. The good news is that Seattle is getting better on this issue over time. Back in the mid-1990s to mid-2000s, every 100 units of new housing required about 14 existing units to be demolished. In the last five years, we're down to 9 demolitions for every 100 new units. And we know how to lower that even further: in our current mid-rise and high-rise construction, only 4 existing units are demolished for every 100 new units built.

A well-planned city provides stability for current residents while still welcoming newcomers and growth. This analysis suggests that our current single-family and low-rise neighborhoods aren't living up to those ideals. Single-family zones as they exist today contribute almost nothing to alleviating our housing shortage, while low-rise zones add housing at the cost of high displacement.

It's unfortunate that so much of our political debate has been focused on these areas, when we already have a successful model for building large amounts of housing with little displacement. With Seattle bitterly divided over low-density neighborhoods, perhaps a more constructive conversation can be had around expanding and improving our mid-rise and high-rise housing.

Graphics by Ethan Phelps-Goodman and Joseph Liu