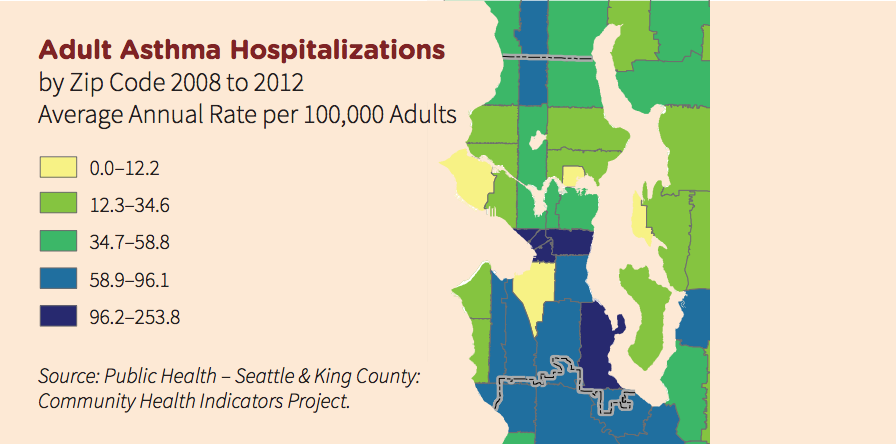

There’s a map that simultaneously illustrates Seattle’s rich/poor divide, and shows how quality of life can differ in unexpected and dramatic ways across that divide. It focuses on adult hospitalization rates for asthma, organized by zip code.

The map is part of Seattle 2035 —the proposed update to Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan that guides the city’s development — and the disparities it illustrates across the city are striking. Adults living south of Denny Street have rates of asthma hospitalization nearly four times higher than that of people living north of Denny.

“Asthma tracks remarkably consistently with poverty at any age,” said Jim Stout, a professor at the University of Washington who is also the principal investigator on a recent asthma study conducted by the county.

The reasons for this disparity are varied, ranging from the mold that builds up in old buildings and carpets, to the prevalence of cockroaches (yes, cockroaches cause asthma and indoor air quality problems). And because of that, the city has struggled to address the issue. In fact, there are concerns that it could complicate the gentrification issue, by making undesirable properties less so, opening them to the competition surging throughout the Seattle real estate market.

Since 1988, the city’s health department has run seven different programs to reduce asthma in impoverished communities. Most have operated under a similar principal: sending community health workers into the homes of individuals with a chronic asthma problem. Once these workers see how the people live, they troubleshoot issues like mold, dust, and animal dander, help the person set goals, and explain the resources available to them.

Health workers have heard a laundry list of other reasons people don’t manage the problem day-to-day. They worry about the side effects of asthma inhalers, for example. They may also be living paycheck-to-paycheck. Managing asthma regularly, as opposed to on an emergency basis, just doesn’t register on their priority list.

“It’s very clear that health is not their top priority for a lot of great reasons,” Kramer says.

Few people prefer to live in the type of housing that contain asthma triggers – they do so generally because they have few other choices. In short, the sub-standard units typically have cheap rent, and are naturally affordable.

In a city that’s undergoing unrelenting gentrification, they pose a problem for the planners developing the 2035 plan. How do we best clean them up, knowing that will make them more desirable, which will in turn make the rents higher, which will force the residents out?

Compared to previous comprehensive plans, the Seattle 2035 plan makes strides in addressing the issue. New to the 2035 plan is a section dealing with social justice, which lists a series of goals designed to make the city more equitable in terms of quality of life.

Jason Kelly, communications director for the Office of Planning and Community Development, points specifically to a goal that the city “seek to ensure that environmental benefits are equitably distributed and environmental burdens are minimized and equitably shared by all Seattleites.”

There are a number of policies under that goal, which generally say the city should consider the impacts of decisions on marginalized populations, and take into account not only the impact of new policies, but also the existing conditions.

The plan also aims to slow gentrification. Kelley points to another goal (H5.10) which, to paraphrase, says the city should find ways to encourage property owners to improve, renovate and redevelop their property, and do so without raising rents. That might sound a little like getting Mexico to pay for a wall, but there is a program in place, the Multifamily Tax Exemption, which does that sort of thing. Originally established in 1998 and renewed last November, the program allows owners of new multifamily buildings to get a tax break if they set aside at least 20 percent of their units as affordable, rent restricted housing.

The work to-date on the asthma issue has been promising locally. Countywide, the asthma hospitalization rate for people living in poverty has been dropping over the past decade. But while the programs may help individuals, they don’t always address the root cause. Even if a resident cleans up their apartment and starts living differently, eventually they’ll move. Now a new person will be introduced to that house or apartment, possibly starting the cycle again.

To address this, city started phasing in a program to inspect every rental unit in town in 2014. If it works as designed, inspectors will make sure those units meet basic safety and health standards. However, the regulations say units only need to be checked once every 10 years, although it’s possible they may be checked more frequently. Complaint-based inspection will also still occur.

Stout is quick to point out the map in the Seattle 2035 plan — which comes from a health department data set — has some flaws. For one, zip codes are a fairly blunt instrument for doing this sort of analysis. They may be fairly compact, but the boundaries are arbitrary and the real dividing lines won’t be nearly as straight.

But in mapping out asthma’s prevalence, the map depicts how issues stemming from poverty can be more wide-ranging than is commonly recognized.