Update: Shortly following publication of this story, a federal judge found the state in contempt regarding a ruling mentioned in this piece, focused on providing timely services to mentally ill defendants. To learn more about the ruling, click here.

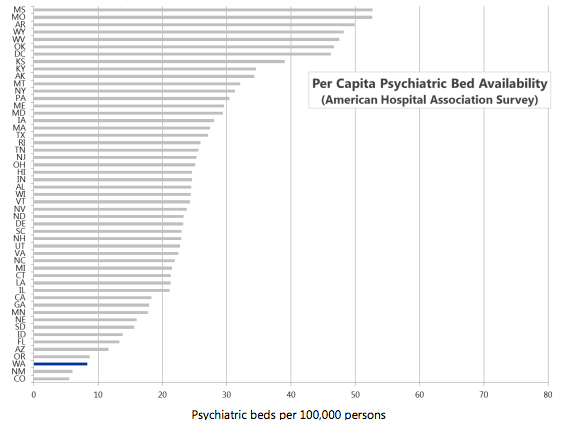

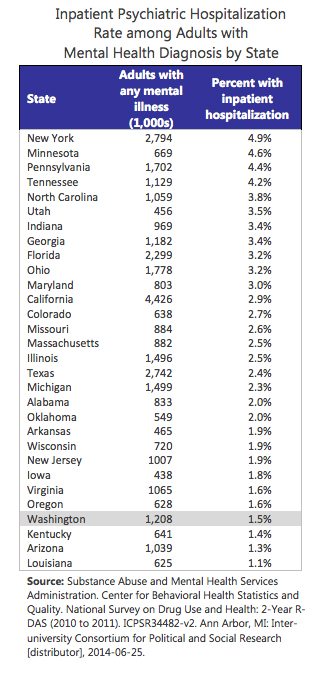

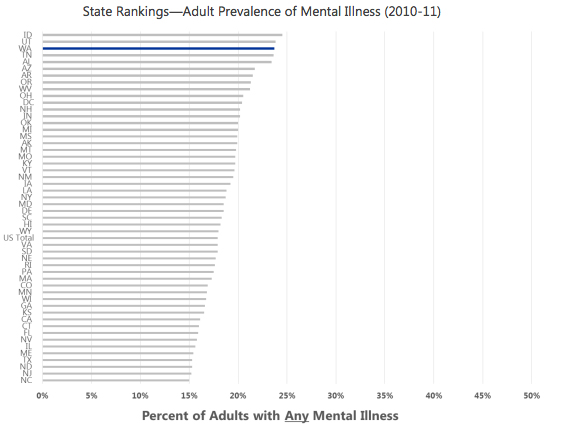

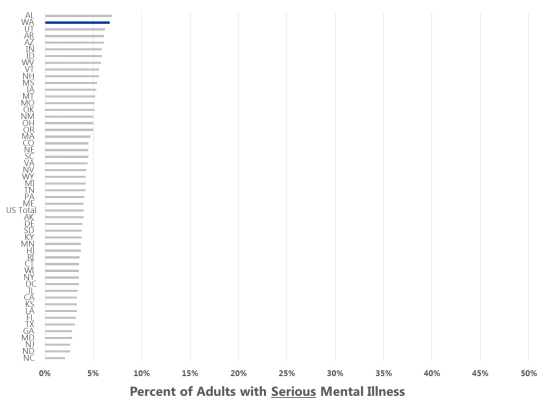

To address the region’s growing homelessness, nearly every major observer — from Mayor Ed Murray to rank-and-file service providers — points to the gaps in Washington’s mental health system as a major priority. By one count, almost a quarter of Washingtonians have a mental health disorder, more than nearly any other state. But when it comes to treating them, Washington is among the worst in the nation.

According to a 2016 report from national nonprofit Mental Health America, there is only one state worse at caring for mentally ill adults than Washington, as judged by the amount of need versus access to care. While the problem predates the Great Recession, that economic downturn led to cuts throughout the system, many of which the state is just beginning to reverse.

Sometimes Washington has gone past neglect, and into practices that can easily be labeled cruel. With mental hospitals consistently over-capacity, for example, individuals have often been detained in general hospitals unequipped to treat them, sometimes left in a drugged-up stupor while strapped down to gurneys. Other times, they’ve been locked in prison cells. This includes not only adults, but mentally ill children as well, who may emerge from this “treatment” with new issues.

Writing in the Seattle Times in 2013, columnist Jonathan Martin noted that at the time there were about 20 mentally ill patients boarding in King County hospitals on any given day, sometimes sedated in hallways. He tells of a mother whose son was strapped down in four point restraints, and later struggled to recover from the humiliating experience.

Long waiting lists for mental hospitals, paired with the lack of community services for people discharged from those hospitals, are named as prime factors behind the growing number of mentally ill people living on the street — they represent roughly 35 percent of King County's homeless by some estimates.

Similar to Washington’s failure to fully fund K-12 education, it took legal action to force legislature to begin acting on the mental health issue. That came in the form of three court cases over the past two years:

- In the most major case, the state Supreme Court banned the use of hospital emergency rooms and hallways to hold mentally ill people when there was no room in psychiatric wards, essentially requiring the state to create more mental hospital capacity.

- The second case forced the state to move more mentally ill people out of prison, by speeding up psychiatric evaluations of defendants.

- The third case required the state to provide care to children with severe mental illness, rather than locking them up in juvenile detention centers or sending them out-of-state.

Those rulings led to a scramble in the statehouse. The last two legislative sessions together have yielded at least $120 million in additional funding for mental health treatment.

Seth Dawson, a lobbyist for the state chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, says this is progress, but also indicative of a deeper problem with the legislature. “We have a crisis-driven system in Olympia, and that’s expensive in both human and financial terms,” says Dawson. “It takes great external pressure to get any movement on important issues, and long-term issues aren’t addressed, because they’re not an immediate crisis.”

Given the latest investments, Dawson believes Washington’s national standing has likely improved since Mental Health America’s latest report, which was released earlier this year. Maybe a few states are more neglectful toward mentally ill adults now, and not just Utah, which ranked last in this year’s ratings.

But asked whether this progress will likely continue once the shadow of court rulings has passed, Dawson is skeptical.

But asked whether this progress will likely continue once the shadow of court rulings has passed, Dawson is skeptical.

The pessimism toward a long-term focus is justified. A look at new state funding shows that beds for short inpatient commitments will soon be at a nearly two-decade high. But over the past decade, the number of beds allocated for months-long commitments has sunk dramatically.

This would be acceptable, even strategic, if there was more help for those with chronic mental illness available outside of the state’s two primary mental hospitals near Spokane and Tacoma. More dispersed, community-based care would allow these hospitals to discharge more patients, clear room for those with more pressing needs, and establish more ongoing help for those in need.

The issue was at the core of a legal case last month, in which the CEO of Western State psychiatric hospital was ordered to jail when she refused to fast-track a patient into the facility. There were over 70 patients on the waiting list for the 800-bed hospital, and over 180 waiting to be discharged. The CEO didn’t end up going to jail, but the judge who ordered her there — Pierce County Superior Court Commissioner Craig Adams — says he remains committed to confronting complacency in the state’s mental health system.

A big part of the problem, according to Washington State Hospital Association vice president Cassie Sauer, is the state forbids inpatient treatment of longer than 90 days in hospitals other than Western State and Eastern State. This is unusual, she says — other states allow for long-term care on a regional level. This allows those who require care to stay in their home communities, and closer to families and loved ones.

“We need to create a better way for these people to land back in the community,” Sauer says. “A lot of times they get discharged, and there’s no safety net waiting for them back home. We need more focus on long-term local services.”

“We need to create a better way for these people to land back in the community,” Sauer says. “A lot of times they get discharged, and there’s no safety net waiting for them back home. We need more focus on long-term local services.”

She calls this one of the biggest links between the state’s mental health crisis and the booming homelessness population.

Bill Block, former director of King County’s Committee to End Homelessness, says that Washington’s homeless services have "become, in some ways, the default mental health discharge system…. As they’ve reduced (mental health) services, without really investing in the community-based services that everybody was promised in the ‘70s when the big move started to close institutions, more folks have become homeless.”

In a recent op-ed in the Seattle Times, Sauer claimed mental health issues were under threat of becoming politicized in Washington. While the op-ed didn’t point the finger at any particular group or individual, in conversation she singles out Gov. Jay Inslee for vetoing key sections a mental health bill passed this session. That bill, SB 6656, would have directed investments to community-based mental health services, among other initiatives.

The bill received bipartisan support. The sole group advocating for sections to be vetoed, she says, was the Washington Federation of State Employees union, because the bill would’ve shifted more mental health care to facilities that weren’t state-run. In vetoing this section of the bill, Inslee said he wanted additional input from a state-hired consultant before making a decision.

As for what the ideal community-based care might look like, Sauer and others cite Seattle’s Plymouth Housing Group as a model. The nonprofit’s housing projects provide on-site health and counseling services, and 24-hour shelter to prevent individuals from falling through the cracks or ending up on the streets.

As for what the ideal community-based care might look like, Sauer and others cite Seattle’s Plymouth Housing Group as a model. The nonprofit’s housing projects provide on-site health and counseling services, and 24-hour shelter to prevent individuals from falling through the cracks or ending up on the streets.

The legislature deserves credit for its recent passion on mental health issues, Dawson says. They’ve passed legislation to better integrate mental illness and chemical dependency treatment in the state, for example. They’ve injected new money into a system rendered anemic by the Great Recession, reversing some of the damage done over the past decade.

But like homelessness, the mental illness crisis didn’t appear overnight, though the focus on it by some policymakers has. “I was at court hearing yesterday,” says Sauer, "and it felt like some people in the room were treating mental illness crisis like it’s Ebola or Zika” — new problems that could be solved with a rapid response.

Instead, advocates for additional services argue that a consistent, year-after-year commitment is the only path toward fixing the state’s abysmal record on the issue.

“We need to get away from what I call ‘admiring the problem’,” says Sauer. “This is not new information that we’re bad at this, and this is not a new problem. This has been a slowly building need, and we need to figure it out.”

--

Disclosure: The author has served on a committee at Plymouth Housing Group

Graphs courtesy of Washington State Institute for Public Policy