Whether sports or news, journalists are taught to be respectful but impervious to authority, celebrity and power. The job cannot be done while influenced by awe, fear or fandom. Any news consumer can spot the difference with one test: Are good questions being asked well?

The test is acute in sports because most every sports journalist grew up a sports fan.

Learning to lock the elbow and hold subjects and passions at a distance often is a hard thing. It's more difficult now because the biggest employers of sports journalists are the sports leagues and conferences, shrewd exploiters of a crashing industry who can offer decent jobs in exchange for a willingness to look the other way during dispute, scandal and controversy.

I bring this up now because I remember how all of that professional impartiality and distance turned to dust one afternoon when Muhammad Ali walked into the sports department of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Ali was in town for a charity event after his 1981 retirement, but before Parkinson's disease claimed so much of his vibrancy. He was staying at the Westin Hotel a few blocks from the P-I offices.

Colleague Kenny Richardson, a sportswriter with some boxing connections, said he was going to walk down to the Westin and say hi to the champ and invite him back to the office.

Right, Kenny. You go. Bring back Jack Dempsey and Joe Louis while you're at it.

About 45 minutes later, in through the department door walked Richardson, silently, with the world's most famous person trailing him. Just the two of them.

Incredulous, I started to rise from my chair. Ali saw me, put his finger to his lips, and I sat down. He stealthily slipped behind copy editor Paul Rossi, who had his back to the door. Ali made a kind of cricket noise with his fingers next to Rossi's right ear.

Rossi brushed at his ear absent-mindedly, and kept working. Ali did it again. Same response. At the third instance, Rossi swung his arm up, started to turn in his chair and got out the word "What — " before Ali stuck his unmistakable mug next to Rossi's.

Rossi's widening eyes seemed to fill his face. He blurted, "Champ!" so that everyone else in the room was at the same stunned attention.

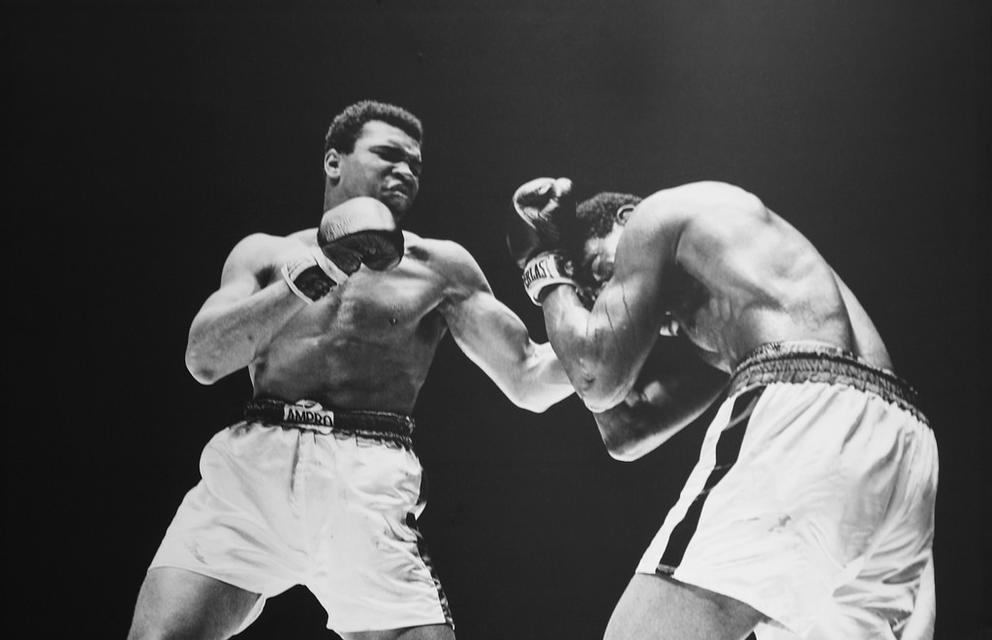

The champ. The Greatest of All Time. The man who fought the most brutal heavyweights of his era, as well as the U.S. military-industrial complex in the courtrooms of the 1960s, was messing with Rossi.

As one of the most courageous cultural figures in history strode toward me with his hand out, my journalism training welled him up and I said, "Shit, man, um..."

As I stood, Ali saw I was taller than him. He grew wide-eyed and said, "You big," and doubled his fists and began to throw shadow punches at me. So I hunkered down and threw hands too.

Then he was off to work the room, greeting and punching with everyone, smiling, saying little. Suddenly he and Kenny were out the door. Journalistic crustiness was nowhere to found.

I felt myself tearing up. I was star-struck. For the first time since I was a kid.

To this day, I don't quite recall how that episode happened. I learned later that Ali often was a master of similar small moments of spontaneity with strangers.

But the emotion I felt from a brush with an unparalleled figure in human history was not just from the amusing moment, but from the sportswriter's knowledge of what he lost, willingly, not what he won.

The admiration had less to do with his prodigious feats in boxing, although I often circled the dates of his fights on the calendar because it seemed everyone in my world, whether kids or adults, whether he was loved or hated, would be talking about what would happen that day.

My fascination and affection for Ali was for his unwavering will to sacrifice for principle. He spoke truth to power. He paid a dear cost, knowing well he would alienate many of those who could make him more wealthy and powerful.

Young sports fans may think that drafts are what sports leagues do to stock rosters. But the draft was what the U.S. government did to conscript young men for wars, be they just or unjust.

When in 1966 Ali loudly, publicly refused to be drafted to fight in Vietnam, he shook a nation already riven with civil-rights protests and anti-war demonstrations. In his hometown of Louisville, at a fair-housing rally, Ali articulated his view with astonishing but characteristic boldness (h/t The Nation):

"Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on Brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? No I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over. This is the day when such evils must come to an end.

"I have been warned that to take such a stand would cost me millions of dollars. But I have said it once and I will say it again. The real enemy of my people is here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom and equality . . . If I thought the war was going to bring freedom and equality to 22 million of my people they wouldn’t have to draft me, I’d join tomorrow. I have nothing to lose by standing up for my beliefs. So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years."

He was convicted in 1967 of draft evasion, stripped of his title and banned from boxing. The appeal process kept him out of jail, and on March 11, 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court, by an 8-0 vote, overturned his conviction.

But he was denied his chosen living for 43 months at the prime of his career. Hindsight says that because of the neurological damage he sustained that compromised his final three decades before his death Friday night, perhaps the pause was a blessing.

That is nonsense, then and now. He was a conscientious objector because of his faith -- an exemption by matter of statute, not opinion -- and was wrongly convicted. He never regained his physical eminence nor the lost income. Yet he fought for another 10 years, twice winning back the heavyweight title in legendary fights against George Foreman and Joe Frazier and not once wavering from his convictions.

In death, he is viewed in many ways by observers of his incandescent boxing career, his social and political activism and his slow, tragic decline. As for himself, not once did he deviate from principle, nor lament its consequences.

"What I suffered physically was worth what I've accomplished in life,'' he said in 1984. "A man who is not courageous enough to take risks will never accomplish anything in life.''

It is difficult to imagine in today's world a successful pro athlete sacrificing so much gain and profile to help achieve a social advance with so uncertain an outcome. Particularly since in the nearly 50 years following his Louisville speech, African-Americans still feel compelled to insist that black lives matter.

The worst outcome for Ali's life is not his physical vulnerability. The worst outcome is yet to play out — will there be among the prominent those who understand the value of sacrifice for principle?

Doubtful.

But I'm eager to be surprised again by someone of conviction to walk through our doors.