Who speaks for Seattle’s neighborhoods? With growth and rezones taking center stage in citywide conversation, the question is getting hotter.

Consider the case of Doug Trumm, a renter and recent transplant who headed down to the Wallingford Community Council to seek a seat on their board. Such contests are rarely contested, but apparently his writings as an urbanist blogger helped draw an opponent.

The council meeting turned unpleasant as one attendee asked Doug: “Why did you move to a city that’s so expensive and then ask the taxpayers to help you?” With renters comprising 52 percent of the city population, and transplants comprising 62 percent, that sentiment is guaranteed to raise hackles.

But it also opens a window into neighborhood level activism, which has a genuine effect on city policy. Even the City Council (on which there are no renters) is weighing in — ordering a review of the decades-old system that built the City Neighborhood Council, a collection of community organizations and councils.

So what are the community councils anyway? Their name suggests they have an official role in the city, but it is an exceedingly slim one. City resolutions acknowledge their existence and guarantee them a seat on one of the thirteen geographically organized Neighborhood District Councils. But that’s about it.

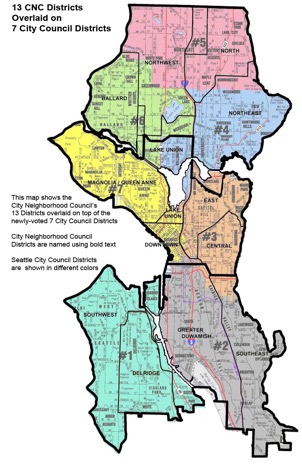

City government uses the District Council structure to share information and discuss issues. The City also asks the District Councils to vet grant requests for Neighborhood Matching Funds and Neighborhood Street Funds. And representatives from the District Council comprise the top of the City-recognized neighborhood pyramid: the City Neighborhood Council (CNC), which provides input to the City Council and Mayor.

City government uses the District Council structure to share information and discuss issues. The City also asks the District Councils to vet grant requests for Neighborhood Matching Funds and Neighborhood Street Funds. And representatives from the District Council comprise the top of the City-recognized neighborhood pyramid: the City Neighborhood Council (CNC), which provides input to the City Council and Mayor.

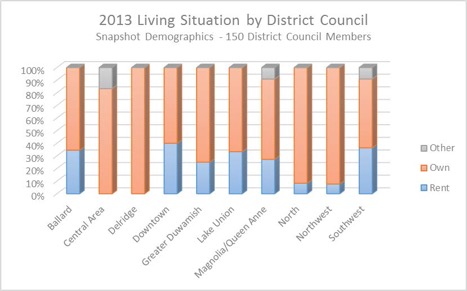

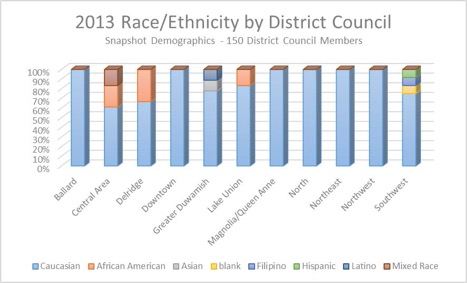

When the City Council was wholly at large, these three tiers had a legitimate claim that their ears were closer to the ground on neighborhood issues, and that their opinions deserved careful consideration. Even so, critics pointed to numerous weaknesses, chief among them that this system was dominated by white single-family homeowners. Indeed, a recent report confirms this charge.

I don’t want to paint with too broad a brush, because each community council and District Council has its own character. There are many very good-hearted people who choose to engage. I was one of them, and made a lot of lasting friendships. But on the whole, their demographics do not represent a city that is younger (median age 36) and more diverse (33 percent people of color), as well as more likely to rent.

District elections for City Council members means seven new contenders for neighborhood top dog. There are relatively few contested elections in community council land — the officer positions are often those with the commitment, ability (and stamina) to attend frequent meetings. City Council members, elected by tens of thousands of voters, have far greater democratic legitimacy.

But don’t count me among those who think these organizations should be counted out. They have an important role, but let’s recognize them for what they are. They are voluntary associations of individuals, working within and across neighborhoods, often without recognition, to try and do some good. They deserve no less consideration than any group of individuals organizing to have their voices heard. By the same token, they also deserve no more.

My experience is that they are often sleepy, unless some controversial issue hits the neighborhood. Then the monthly meetings fill up. And nothing fills them up faster than new development or a proposed change in zoning.

In this regard, telling neighborhoods that there was a “Grand Bargain” on zoning before they had any input was bound to inflame opposition. During my own term, I will take a mea culpa for proposing zoning outcomes in Roosevelt without first talking to neighborhood groups. While I stand by my policy decision then, I also learned that neighborhood organizations deserve authentic engagement, not faits accomplis.

So what do you do if you want to engage in neighborhood politics like Doug did? Ideally, the community council should be the place where neighbors can hash out competing concerns so they can speak with one voice to city government. Many invite participation and strive to reach that ideal.

But one might also discover entrenched leadership in these groups that does not welcome new ideas or viewpoints. In fact, one community group in Northeast Seattle may explicitly ban renters from membership. In this case, find another way to get involved, whether with a neighborhood or city level group. I recently interviewed Sonja Trauss, San Francisco YIMBY (Yes in My Backyard), who got her start testifying at planning meetings with some friends. Now she’s making national news, with a story in the New York Times highlighting her fight with the city’s homeowners and political powers-that-be.

Laura Bernstein recently founded District 4 Renters Council. I founded Great City. Cathy Tuttle founded Seattle Neighborhood Greenways and now has numerous neighborhood-based groups working on safe walking and biking routes.

Immigrant and refugee mutual assistance groups organize around their shared experience. Churches organize around their faith and values, trade organizations around their businesses and unions around their workers. Numerous organizations form around issue advocacy. All have a role in speaking up about neighborhoods, even if they are not organized geographically.

While it’s great to get engaged to speak up for your community, we also need to recognize that not everyone has the same resources or time to commit to organizations. That means they will not have the same access to policymakers, which puts an additional responsibility on those who do.

Because here’s the deal: anyone who claims they “speak for neighborhoods” isn’t being straight with you. So far as I can tell, pretty much everyone lives in a neighborhood, so opinions within them are as diverse as the people of this city. That means city government should not privilege any particular group as being the authentic voice for neighborhoods. Ultimately, that has to be earned through the quality of an organization’s work, including their ability to engage a wide range of viewpoints and experiences.