When it comes to the merits of desecrating graveyards, you’d likely find champions among some local housing density zealots. “Sure, it’s disrespectful to build micro-apartments on top of the dead,” they might say. “But are these cadavers using that space effectively? If we’re going to keep this city affordable, we need to prioritize the living, think outside the box.”

Seattle’s diehard “urbanists” can be remarkably single-minded in their advocacy for new and denser housing, but they aren’t necessarily wrong. In fact, according to some recent number crunching on San Francisco’s rental market, they’re essentially correct on what it’ll take to bring the city’s skyrocketing rents back down to earth.

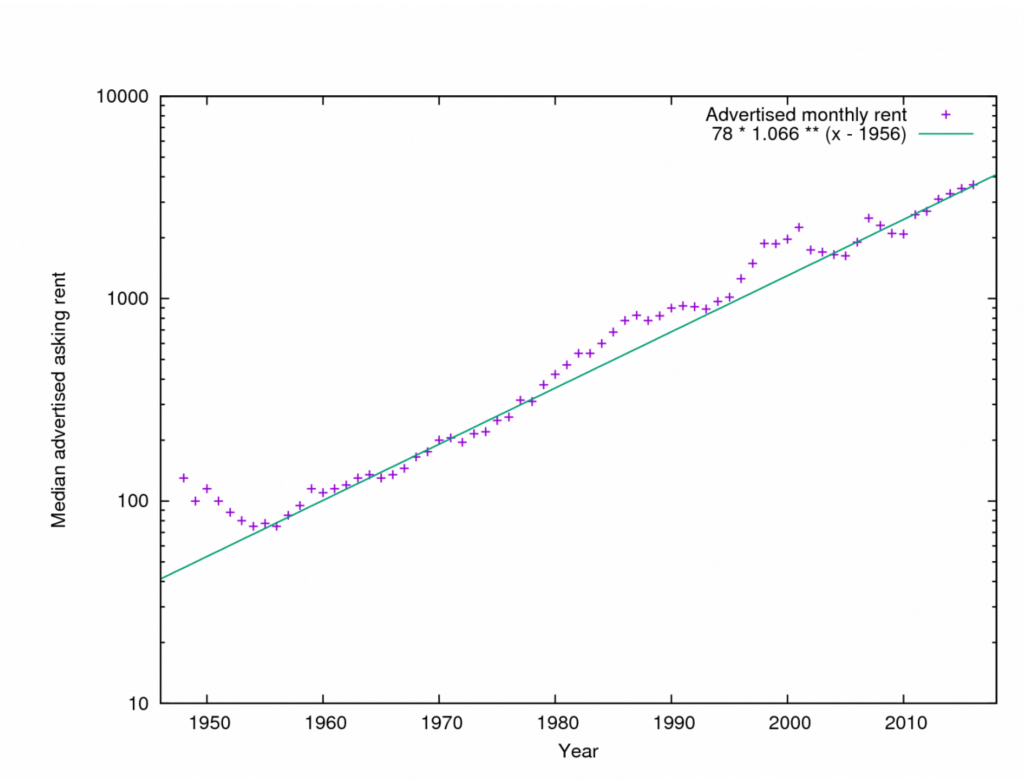

The Washington Post recently highlighted an analysis of San Francisco’s rental market by Eric Fisher, a computer programmer with a laudable dedication to data-digging. Fisher combed through roughly 70 years of rent prices in San Francisco, cross-referencing them with the city’s economic history and policy changes to create a mathematical model for predicting rent hikes.

Adjusting for inflation, Fisher found that San Francisco’s rents have consistently risen about 2.5 percent a year, with only a few slight deviations. This, despite a period of population decline, the introduction of rent control in the late ‘70s, and a few tech booms and busts.

The basic conclusion of Fisher’s analysis is that it’s extremely hard to bring rents down in a prosperous city. Only two things can really accomplish it: more housing units, or fewer jobs — particularly high-paying ones. That’s it.

One Twitter user summarized the study succinctly: “We can have Prosperity, Preservation or Affordability, but we can only pick 2.”

The city’s preservationists would like to make this black-and-white fact a bit grayer. And their dismissal of urbanist arguments about affordability becomes easier when looking at the price tags on the city's new developments. Across the street from my apartment, for example, a single family home recently sold for around $400,000. It was turned into three townhomes, each selling for $600,000. That sort of flipping is not uncommon.

Also helping to rile opposition are hardcore density advocates like Smart Growth Seattle director Roger Valdez, who provide easy villains (he might actually agree with the graveyard example). During one conversation with him, I tried in vain to find any restraint he’d support on real estate developers, anything that might cut into their profits: more on-site affordable housing, just a little parking, minimum space between buildings, anything. He wouldn’t bite. When I suggested that the city should restrain the construction of buildings so ugly or bland that they’re an insult to one’s sense of sight, he replied simply, “Beauty has a price." He disagreed, in other words, that buildings should generally attempt to look good.

And so you have scenes like a recent meeting in the University District, where a number of anti-growth groups came together to prevent upzones in the neighborhood, which would allow taller buildings and more density. A mailer they sent to promote the meeting read: “Our diverse mix of low cost affordable housing, shops and businesses all would give way to steel and glass towers UNLESS WE STOP IT!”

But whether or not they admit it, these advocates aren't that dissimilar from those who’ve helped render the Bay Area unaffordable. As I wrote for Seattle Magazine back in 2014, one reason San Francisco hasn’t built enough housing to meet demand is a concern for preserving the city’s “character.” Replacing some of those Victorian townhouses with structures that house more people is seen as an attack on the city’s very soul.

Similar to San Francisco, Seattle’s “charm” is part of what makes it great. Density isn’t the end-all, especially if it’s a pure giveaway to developers without reasonable support for affordable housing and economically integrated neighborhoods.

But we also must admit that those individuals fighting density at all costs — unless it’s located in neighborhoods other than their own — are fighting to make the city less affordable in the long run. They’re fighting to preserve a version of Seattle that was within their price range decades ago, but is affordable to less people now.

Seattle was just ranked the third best city for job seekers in the United States. The flood of new residents with well-paying jobs isn’t going to change any time soon. The only thing that can change is the tenor of our housing debate, and the willingness of some people to face the facts about what will prevent Seattle from becoming the purview of millionaires, as San Francisco has.

Advocates for the status quo are usually the most vocal participants in the housing debate. They’re often the biggest donors to local politicians, and have the most clout within local power circles. For the good of the city’s affordability, however, the data dictates we ignore them more often.

--

Additional research by Chetan Sharma.