In a grove of cedars where sword fern erupts from mossy ground, you hear the textured rush of flowing water. Look out between cedar trunks, and there's the Green River, running over rocks, dividing around a boulder, just below sandstone cliffs in Flaming Geyser State Park.

You'd never guess it would make a list of the nation's ten most endangered rivers. But this week, conservation group American Rivers' announced the river — actually the Green-Duwamish, pairing the river that flows past those cedars with the famously polluted waterway into which it morphs before it reaches Elliot Bay — is number five in the United States.

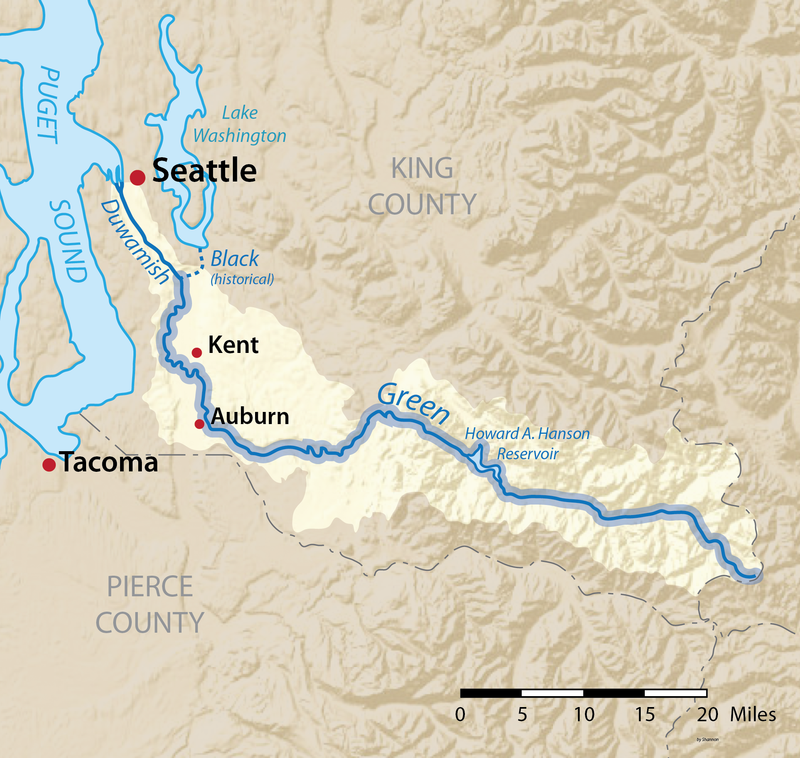

Downstream, in Kent, it's easier to see why. There, the river flows silently between steep levees, and the background noise is I-5 traffic. Upstream in Auburn, close to the river, there are neat rows of semi-trailers, lots full of parked cars, an archipelago of light-industrial roofs, signs of the decades of development that threaten the river.

American Rivers notes that the Green's floodplains have been overdeveloped, salmon can't reach habitat above Howard Hanson Dam, and a lack of shade along the levees lets water get too warm for the fish. The report also points to polluted runoff downstream along the Duwamish.

In 2009, a leak appeared on the earthen face of the Howard Hanson flood-control dam upstream, between Auburn and Enumclaw. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers warned it might have to store less water than usual, creating a risk that heavy runoff could get past the Green River’s levees. Damage to homes and business would potentially run over $4 billion, according to federal estimates.

It never happened. But the doomsday scenarios made it clear — in case anyone had doubted — that the river valley’s development has made the Green too big to fail, at least in terms of flood protection.

One doesn't usually read much about the Green. Unless one visits parks in, say, Kent or Auburn, the river tends to remain out of sight and out of mind. It’s main claim to fame are headlines from the 1980s, which associate it with the Green River Killer, Gary Ridgway.

Long before Ridgway started dumping bodies in the riverside brush, the river had been changed to accommodate growing settlement and development, caught up in the larger drive to tame nature for commerce. The efforts to control the river included separating the White River from the Green and the construction of Mud Mountain Dam on the White as well as the completion of the Howard Hanson Dam on the Green in the early 1960s. (For details how the changes reshaped the Green-Duwamish, click here.)

After the 2009 scare, the Corps spent $40 million on repairs and improvements on the Howard Hanson Dam. The scare also led the Corps to conclude that instead of protecting the valley from a 500-year flood, which people had assumed, it would only offer protection from a 140-year flood. The King County Flood Control District now plans to make the levee and flood wall system from Auburn north robust enough to fulfill its original, once-in-500-years mission.

The district was created in 2007 by the King County Council, which funded it with a new stream of real estate tax revenue. County council members sit as the supervisors of the flood control district, separate from the rest of county government. Councilmember Reagan Dunn, who chairs the flood district, has described the "tension” between the County Executive and the flood district, suggesting that if the county bureaucracy took over, "much more of those dollars would be going for salmon protection and less and less to actual flood protection."

Current plans do not have much to offer fish, whose welfare is a big reason the river was listed as “endangered.” A salmon spawned in the Green River faces several problems.

Neither dam on the Green or White River was built with fish passage in mind. Fish can't even reach the dams. On the White River, they encounter a weir known as the Buckley Diversion, where some are trapped and hauled above the dam. The Corps has agreed to build a new trap-and-haul facility by 2020.

This past year, some 450,000 pink salmon were hauled around Mud Mountain. With the much larger new design, they will be able move up to 1.2 million, the Corps' Johnson says. That would be "far and away the most fish that anybody in the world is doing by a trap and haul." But completing it will be contingent on federal funding.

On the Green River, the fish can't pass a City of Tacoma water diversion. Under a habitat conservation plan approved by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the City of Tacoma has created a trap-and-haul operation to get fish upstream. The operation remains on hold until the Corps creates downstream passage, however. Last October, NMFS sent the Corps a draft biological opinion stating that continued operation of the Howard Hanson Dam would jeopardize the existence of Puget Sound Chinook, Puget Sound Steelhead and Southern Resident Killer Whales, which eat the Chinook.

Fish are cut off not only from habitat upstream but also from the complex network of channels and basins into which the river used to flood. That old flood plain was all habitat for fish, one of the types of places that University of Washington geologist David Montgomery has suggested could again be the region's "salmon factories." In some places, it would make sense to buy out property owners and let the rivers flood once again. In much of the Green River Valley, though, flood control has just encouraged more growth, making costs prohibitive.

But to save the river’s habitat, everyone recognizes that just building levees higher isn't the only alternative. One can move a levee back, creating more natural habitat and giving floodwaters someplace else to go. The area's poster project for this is the Calistoga Levee, which was set back a few years ago to widen the Puyallup River channel two to four times, reconnecting the river to acres of historic floodplain. It improved flood protection so much that Orting stayed dry during major flooding two years ago.

The Calistoga levee setback makes a good advertisement for the Nature Conservancy program "Floodplains by Design," which aims to improve flood protection and habitat. The Legislature started funding such integrated projects on Puget Sound rivers in 2013. The Nature Conservancy’s Bob Carey says that his organization first got involved in flooding issues on the Skagit and Stillaguamish rivers, where farmers were suspicious of support salmon recovery efforts. So, he says, "we essentially sited and designed a couple of projects [that] not only restored habitat but also improved their drainage and flood control structure so that their surrounding farmland would remain viable. " Everybody won.

The state is funding one Floodplains by Design project along the Green: the Lower Russell Road Levee setback in Kent. There's a natural area behind the current levee, and government will take advantage of it to let the river spread out. It's still being designed, with construction slated to begin in 2017. King County Flood Control District executive director Kjristine Lund, says additional funding sources are needed, but the project's multiple benefits — creating habitat as well as increasing flood safety — made it a state priority. "I think people are viewing it as a template," she says.

The Muckleshoot Tribe would like to see the project do a lot more for fish. Tribal fisheries biologist Holly Coccoli wrote in a letter to King County officials that the current design "fails to meet even our minimum objectives for riparian and aquatic habitat."

Still, she says, Lower Russell Road "provides a rare opportunity to restore aquatic and riparian habitat for salmon.” Likewise, State Department of Ecology northwest regional director Josh Baldi says the ability to use public lands, with no land purchases, makes it somewhat unique, but it does "demonstrate more hope for progress."

Levee setbacks also provide opportunities to plant shade trees, crucial for salmon and their need for cool waters.

"In the summers," says Michael Garrity, American Rivers' director for rivers of Puget Sound and the Columbia Basin, there's "really a horrible water temperature problem" on the Green. Even where trees grow on the levees, they tend to be small. According to one study, only 3 percent of stands on the lower river provide adequate shade.

There's even less shade than there used to be. In 2009, the Corps announced it would no longer pay for flood disaster relief if a levee had trees more than 2 to 4 inches in diameter growing from it. Trees make a levee harder to inspect. And if they topple over, their root balls can leave holes that threaten a levee's integrity.

This led to 500 trees being taken down along the Green. But faced with complaints from California and an environmental lawsuit, the Corps ultimately stepped back from that position, suggesting local districts can create their own vegetation standards.

Local governments certainly want federal agencies to approve of their levees. Build a levee. Get it certified by FEMA. Voila! You're no longer in a flood hazard area. As King County Executive Dow Constantine wrote to the county council during a 2013 discussion of improving the levee along the Green in Kent and Tukwila, "certification is expected to reduce the area that is mapped as flood hazard and the number of properties subject to flood insurance purchase requirements." However, he warned, that certification “does not necessarily reduce real flood risk and could have the unintended consequence of providing a false sense of security."

In response, county council members voted to bankroll a steel floodwall on the existing Briscoe-Desimone levee, for a price of $18 million.

When the flood control district approved the levee project, it also launched a System-Wide Improvement Framework (SWIF), which people expected to produce a holistic approach to the Green, balancing increased flood protection with habitat improvements. It didn't. An interim SWIF plan, approved in February, talks about adding shade vegetation along the water, but there is no plan or commitment to do so.

"It's a maddening situation," says Earthjustice attorney Jan Hasselman. He sees "a consistent pattern of looking at levy repair and replacement in isolation. It's business as usual and ultimately means no more Green River salmon." The process of looking at opportunities to restore habitat has been "well-intentioned," he says, but it hasn't really gone anywhere.

Critics also complain that the flood control district has disregarded expert advice so far. After the Howard Hanson dam scare in 2009, an outside advisory committee that included University of Washington geologists Montgomery and Derek Booth recommended widening the river's flood channel; planning projects for multiple benefits; and coordinating floodplain planning among the valley's many political jurisdictions. They see little evidence of results.

Garrity had hoped for more from the flood control district's interim plan, which was adopted in late February. He says the plan basically adopts flood protection targets, and not much more. All-in-all, he says, it adds up to "a pretty big missed opportunity."

"I can understand why people have that sort of impression," Flood Control District Executive Director Lund says. The planning process did not lead where people had expected it to go, and "our communications with the stakeholder groups have been less than ideal."

She says the flood control district had assumed that the Corps would approve the plan as an integrated whole and then use it as the basis for an Endangered Species Act consultation regarding listed salmon and steelhead. Instead, part way through the process, the Corps made clear its belief that it could approve the SWIF without a programmatic consultation.

At that point, Lund says, the district made a decision: "'Let's shut this thing down and do the minimum'" to keep the levies eligible for federal spending on their repair. The group prioritized the Lower Russell Road project, identified other possibilities for multiple benefits, and shipped out an interim plan.

Now, she says, "our intent, and we are moving forward with this, is that we restart a planning process for the lower Green River.” The new plan can then lead to the ESA review. She expects the county council — as the flood control district board of supervisors — to approve funding in another month or so.

American Rivers’ Garrity says it hopes, among other things, for better local funding for Green-Duwamish protections, and a firm Corps commitment next year on fish passage at the Howard Hanson dam by 2021.

Ecology's Baldi says "the flood district has made it pretty clear that they feel their job is flood control," and suggests that Ecology may have to look at ways of requiring compliance with the state's Coastal Zone Management Act. Still, he says, "at least we're having this conversation.”

Even before it was listed as among the most threatened rivers in America, she says, “I don't think there's been this much energy and attention or frankly progress on the Green in a long time."

This story has been updated to clarify a distinction between the county government and the flood district.

For an article on the Duwamish last year, click here.