Many readers have asked me what my inspiration was for digging into Seattle’s Nazi past. Most seemed to assume it had to do with Donald Trump and the whiff of fascist politics from a guy who pitches himself as a nationalistic strongman.

But that wasn’t really the case.

What inspired me was an Amazon original TV series based on Philip K. Dick’s novel, The Man in the High Castle. It’s a dystopian alternative history that imagines that the Axis powers won World War II. Most of America has been absorbed into Hitler’s Third Reich, the West Coast is ruled by Imperial Japan, and a thin stretch of the Rocky Mountain states is a kind of no man’s land. Set in the early 1960s, most of the action takes place in San Francisco, where large Swastika banners hang from buildings and the SS is ever present. We also learn, this being a science fiction series, that there are alternate timelines with different outcomes.

Some shots were filmed in Seattle, too. Our Alweg monorail is seen gliding through some scenes — it feels a bit like world’s fair futurism is married to Hitler’s plans for domination. That’s not far-fetched. The Alweg was designed by a Swedish industrialist, Axel Wenner-Gren, who was considered by our FBI to be way too friendly to the Germans before and during WWII. Our monorail — like Disneyland’s — was crafted after the war in Cologne, Germany, by hands and minds that once helped the Luftwaffe fly.

The Amazon series got me thinking: What about real Nazis? Not neo-Nazis, not fictional Nazis, but actual representatives of the Third Reich and their fellow travelers? Were they here in Seattle? Turns out, they were, all up and down the Pacific Coast. Some were diplomats, some visiting members of the Gestapo and SS. They were businessmen and trading partners, spies, propagandists, they were local German Americans who believed Hitler was the savior of their homeland and could teach American a thing or two about how to run a country.

In The Man in the High Castle, Nazi banners hang from public buildings. That image is perhaps an echo of the fact that a real giant Nazi banner once hung from the German consulate in San Francisco. In January 1941, a young American sailor from the U.S. Navy destroyer Craven, Harold Sturtevant, climbed to the ninth story of the consulate and, with help from some fellow sailors, cut the Nazi flag down in front of a cheering crowd of 2,000 people.

In the 1930s, swastikas were also displayed at public rallies and ceremonies in Seattle. Knowing that pro-Hitler speeches and swastikas were part of public events in places like the old Masonic Temple (now the Egyptian Theater) and German House on First Hill has changed the way I see those buildings. If we preserve historic buildings, as we should, it’s important to learn their histories, to know what happened inside them. I get a chill when I see these buildings now, trying to imagine people inside giving the Hitler salute.

Some other things linger with me.

One is the reminder that while Seattle once seemed like a remote, provincial city disconnected from the world, history repeatedly tells us it was not. The European settlement of our region was connected to global events — trade wars and real wars — between empires, not to mention the national policies and ideologies promoting U.S. expansion. In the 1930s we were connected by ships and planes to global trade and politics. The war happened here, even if the fighting took place elsewhere. We were shaped by the defense industry — the shipyards, Boeing, military and naval bases, Hanford, surges and flows in populations that reshaped the city. The war put women to work and saw our African American population boom and thousands of Japanese shipped off to concentration camps.

The scale of the crackdown against suspected Nazis after Pearl Harbor paled against what was unleashed against Japanese Americans. Some 120,000 people of Japanese descent were sent to camps, approximately two-thirds of them U.S. citizens. Even though the population of Germans and German Americans was much larger, the number of Germans interned was only a fraction of that number, some 11,000, almost all of them non-citizens. German Americans who were charged with crimes were generally dealt with individually with a chance to defend themselves in court. The Japanese Americans were handled collectively with little redress.

The difference wasn’t lost on some people. Gordon Hirabayashi, the Seattle pacifist and U.S. citizen who was jailed for famously and bravely resisting internment, commented on the disparity in treatment while writing in his diary in a King County jail cell in 1942: “In contrast to these largely peaceful and patriotic Japanese-born citizens, are the Italo-Americans with their numerous Fascist leagues and the German-Americans with their bunds. Although they constitute a greater menace than the Japanese Americans because they can spy more easily (being white), they are unmolested.”

Racial bias was a deciding factor in how potential Asian and European “enemies” were treated, even as we were fighting ideologies based on racial and ethnic hate.

In combing through newspapers of the pre-war era, a couple of things jumped out. The U.S. media notoriously underplayed the march to the holocaust. As I pointed out in my series, the Seattle Times’ editorials saying that German persecution of Jews was not happening and would never happen are indicative of propaganda lines that Hitler’s representatives were selling here and worldwide. But at the same time, newspapers were reporting much of what was happening in Germany, as shown by recent crowd-sourcing research on what the U.S. media knew and reported before the war. I don’t have an explanation for the disconnect between the news pages and the editorial pages, or what did or didn’t strike a chord in public consciousness, but I can’t help but feel that most people simply didn’t care about the plight of Jews, at least not before Pearl Harbor. It’s worth remembering, too, that Seattle’s housing covenants and exclusive clubs also routinely excluded Jews, along with blacks and Asians.

But there were media that did see what was happening. The Jewish Transcript’s electronic archives demonstrate that and are worth digging around in. Left-wing labor newspapers, too, were full of warnings and reports of atrocities, often dismissed on the basis of ideological bias and loyalties to the Soviet Union. It turns out that the Jews and Communists were more right than the mainstream media. We often dismiss people with a large stake in events or politics as being biased, but sometimes they are better informed.

Some atrocities were not fully appreciated until the end of the war.

In 1945, German military prisoners — more than1,000 of them — were held at Fort Lawton in Magnolia (now Discovery Park). The POWs were mostly in their 20s and had been taken prisoner in North Africa or Normandy. They were used as laborers, loading and unloading ships, some were sent to Eastern Washington to help with the fruit and vegetable harvests due to the wartime labor shortage. The last of the prisoners weren’t sent home until 1946, nearly a year after the war in Germany ended.

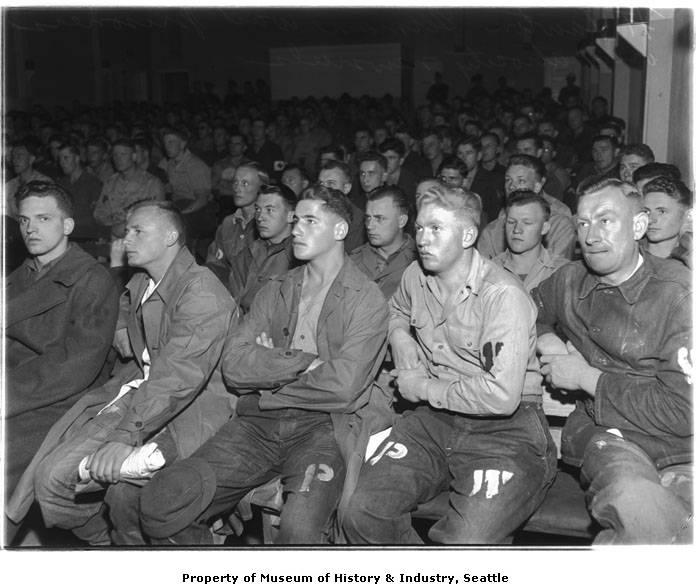

While still here in 1945, the POWs were shown newsreels taken by the military of the liberation of the concentration camps like Buchenwald. “Among the pictures shown were stacks of nude, emaciated corpses in hug common graves, torture racks and rows of oven in which the victims of Nazi cruelty were cremated,” reported the Seattle Times. The paper noted that some of the POWs were jovial as they left the screening. “Their light-heartedness does not indicate they were greatly moved by the horror of what they had just seen,” observed the Times.

But there’s a photograph from the old Seattle Post-Intelligencer at the Museum of History and Industry that suggests otherwise — a room of men who seem riveted by the screen. Maybe they laughed off tension afterward, but in the screening room they appear sober, tense. Their discomfort is palpable.

There were times while digging into Seattle little-known Nazi past that I felt just like that.

To read the Nazi series beginning with the first story, click here.