Sixth in a series

Pearl Harbor changed everything for America’s Nazi sympathizers.

German diplomats had been expelled from the U.S. earlier in 1941. In the days following the Japanese attack in December of that year, the FBI swept down on suspected Nazis. They made arrests, confiscated papers, literature, records, weapons, pictures of Hitler, anything that might be used as evidence against them. This included American citizens as well as resident Germans who were now considered “enemy aliens.” Some were jailed, others sent to internment camps, a couple of hundred were exiled from coastal cities by order of the military.

Major targets of the post-Pearl Harbor FBI sweeps included the leaders of the pro-Nazi German American Bund, such as Hermann Schwinn, the West Coast head of the Bund, who was arrested, as was the head of the Seattle Bund, William Ottersbach. Some 800 naturalized U.S. citizens from Germany were targeted by the government to have their citizenship taken away — denaturalization it was called. The highest profile Seattleite to be subjected to this process was attorney Hans Otto Giese. His fight with the government was front-page news in Seattle during the war.

Giese was a high-profile leader of the German-American community in Seattle. A University of Washington law school grad, he did legal work for and through the German consulate here and had friendly social and business relations with Germany’s diplomats. He had even been sounded out about the position of honorary consul after the San Francisco-based Consul General, former Hitler aide Fritz Wiedemann, was expelled from the country in 1941. Giese declined. After the war, perhaps, Giese had said.

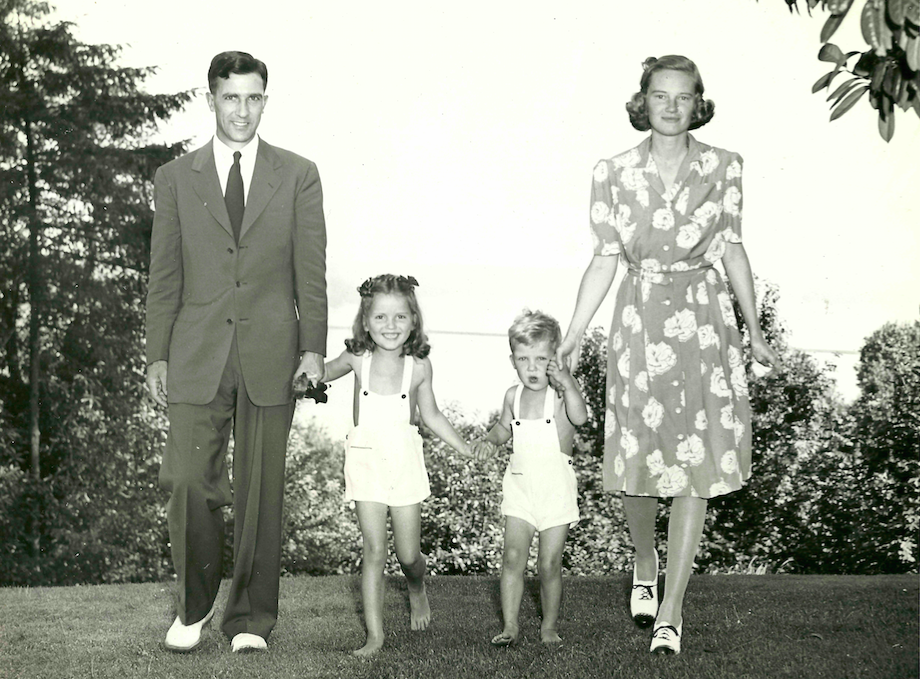

More broadly, Giese — a handsome, athletic man who seemed to embody the Aryan ideal — was a pioneering skier and yachtsman in Seattle. A native of Germany he had immigrated to the U.S. in 1923 and brought a passion for skiing. For some years he was considered the best skier in the Northwest. He was a founder of the Seattle Ski Council, organizing competitions and helping spread the popularity of the sport through Seattle schools. He was key to bringing the 1935 Olympic ski tryouts to Mount Rainier. With the Mountaineers, he made first ski ascents of all four of the main Cascades volcanoes, Rainier, Adams, St. Helens and Baker, thus he pioneered ski mountaineering in the region. Ski historian Lowell Skoog says, “I think you could say with confidence that from the mid-1920s through the mid-1930s, which was the infancy of alpine skiing in our region, there was no more important contributor to its development than Hans Otto Giese.”

He was equally at home at sea as on the slopes. Giese was a well-known sailor who helped to found the Corinthian Yacht Club, which still gives an annual award named for him. His 36-foot sailboat, the Oslo, which once belonged to the king of Norway, became a local fixture, and it’s still afloat. It was purchased during a trip to Norway that also included a visit to Germany, where Giese and his wife attended the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

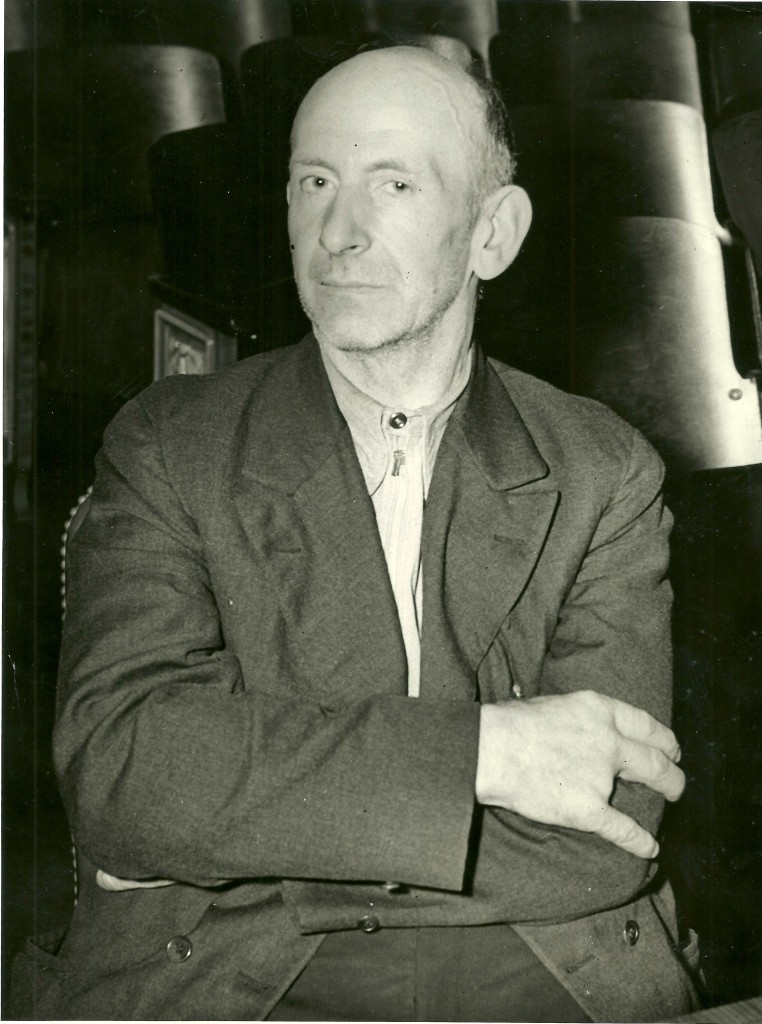

Giese’s office was raided two days after Pearl Harbor, his papers seized, and he was banished by the military from the city pending his denaturalization proceedings in U.S. District Court in Seattle in 1943. He moved temporarily to Denver. Federal prosecutors alleged that Giese had obtained his citizenship while retaining loyalty to Germany, thus had taken his oath fraudulently.

There’s little question that Giese was proud of his German heritage, maintained strong connections with both Germany and the German community in Seattle, and that in the 1930s he admired Adolph Hitler, while being a vocal defender of his homeland. He also defended his loyalty and American citizenship fiercely.

In 1933, Giese had helped found the Seattle unit of Friends of New Germany in response to a Jewish boycott of German trade. That organization later changed its name to the German American Bund. Giese claimed he had quit the group in 1935, but in 1936 he still spoke against the what he called a “small, well-organized minority [that] can agitate unhindered against our Fatherland … unpenalized for a boycott of German goods.” Giese admitted he had raised his hand in the Hitler salute at local German Day events — a “courtesy,” he said — but he maintained that he had never “heiled Hitler.” He had entertained visitors to Seattle from Germany, including members of the Gestapo and SS.

Giese maintained that he wasn’t anti-Semitic, saying that the best man at his wedding had been Jewish, but in various speeches in German he had extolled the virtues of the Third Reich. In October 1937, in a speech entered as evidence at his trial, Giese told his audience, “We frankly admire our reborn and united German fatherland of today and its greatest genius, Adolph Hitler, who has accomplished such wonders over there in restoring national unity and social peace.”

Many German Americans admired the order and economic boost Hitler brought to the post-World War I conditions that had made it so hard on the families of immigrants that stayed behind. And admiration of Hitler hadn’t been limited to German immigrants. American icons like Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh had also been fans. In January 1943 Giese told an FBI interviewer, “[W]e all admired him until the war started. We didn’t admire him for the one thing with the Jews … but as a whole, the man is a historical figure. … If he turns out to be a big rascal in the end, that’s that. But he has made a new Germany.”

A photograph of Hitler had hung in the Giese home. At trial, a good friend of Giese’s, Goodwin Chase, Jr. of Washington National Bank in Ellensburg, testified that Giese had seen Hitler in 1936 at the Olympics and had said that he had “kind blue eyes.” Giese’s wife, Borghild, born in Canada of Norwegian extraction, testified that they had not got within 200 yards of Hitler. Giese’s son Peter, born after the war, says that his father began to have a change of heart after his trip to the Olympics. Borghild said that while there, Otto had extolled America’s virtues. Giese himself dated his disillusionment to 1940 when the Germans invaded Norway. That was when they took Hitler portrait down, Borghild said, and consigned it to a “junk room.”

Giese mounted a strong defense at trial. A parade of prominent local attorneys and businessmen testified to his loyalty, citizenship and honesty. After Pearl Harbor he’d taken first aid lessons and became an air raid warden. His own defense attorney, Stephen F. Chadwick, was Exhibit A as former national Commander of the American Legion, a group well known for its anti-Nazi stance. Chadwick defended Giese’s right to free speech and called him “a victim of the intolerance born of all wars.”

A prominent doctor, Carl S. Leede, testified, “Giese did not advocate national socialism here. But he did seem to make it understandable to us. I don’t know whether he was trying to be fair or whether it was the exuberance of youth, or a friendly feeling toward the German Reich.” Perhaps it was all of the above. Peter Giese says his father “was always very proud of being German” and that “I infer the pride of Otto to the Nazi regime, as leading Germany to economic vitality.”

Giese’s defense was boosted by a couple of Supreme Court decisions that made it much more difficult to take citizenship away once it had been conferred, a victory for civil libertarians and naturalized citizens of all ideologies and backgrounds. It became possible to be a naturalized U.S. citizen who held “un-American” beliefs — just like every other American citizen. The federal judge in the Giese case, Lloyd Black, wrote in his decision in the case in 1944:

“Under the clear preponderance of the evidence [Giese] was closely associated with a small spearhead of Hitler and Nazi admirers in Seattle which was very active in attempting to control some important German organizations in Seattle in behalf of Hitler. The well executed plans of such small minority partly succeeded for a while although under the evidence at the trial the very great majority of the German people of Seattle were for the entire period thoroughly loyal to the United States and not at all favorable to Hitler.”

Still, Black found that federal prosecutors had failed to prove that Giese had fraudulently become a citizen in 1930, and that he had not committed any overt act that could be cause to lose his citizenship.

Giese felt fully vindicated. The government decided not to appeal. In fact, most government denaturalization attempts against suspected Nazis failed. By 1945, Giese was completely off the legal hook and was able to resume life, outdoor activities and his legal practice in Seattle.

While most of Seattle forgot the pre-War years and the presence of the Third Reich’s representatives in the city, for Giese those memories lingered too long. In a 1985 Seattle Times profile by Don Duncan, Giese, then 82, encouraged locals of German blood to join German cultural groups and re-embrace their heritage. “The war has been over for a long time,” he told Duncan. “It's time that Germans quit apologizing.”

But for the rest of Seattle, the memories of the tumultuous times before Pearl Harbor disappeared quickly, too quickly. When it came to Nazis and their sympathizers, post-war Seattle seemed almost eager to forget.

Earlier stories in this series are here. To begin with the first story in the series, click here.