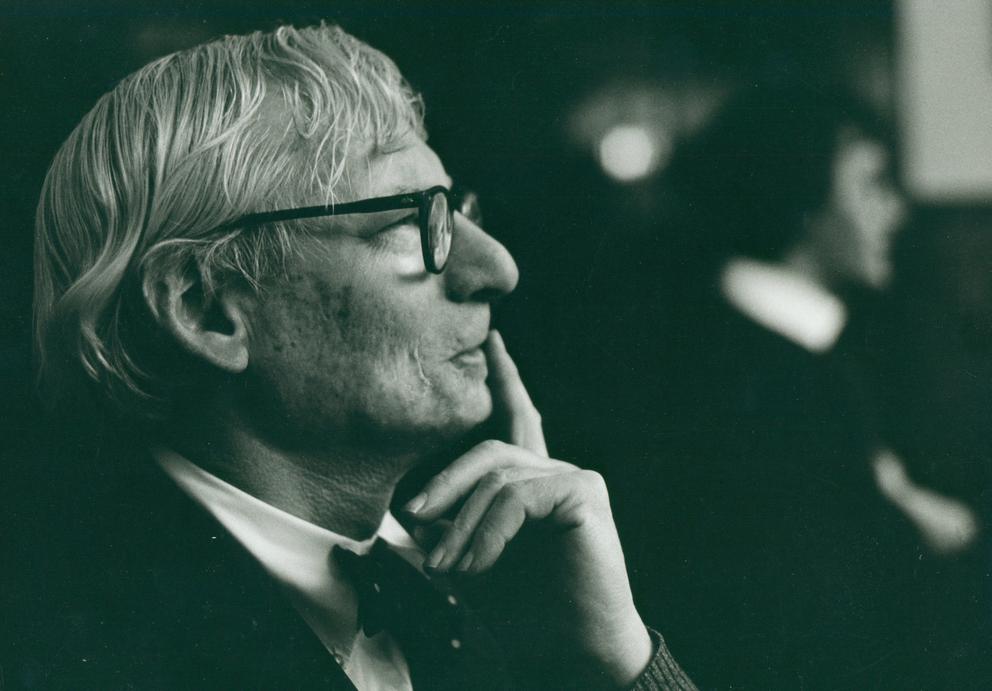

The two New York cops discovered the old man’s body in a men’s room toilet on the lower level of Penn Station. It was Sunday night. The only ID was a passport issued to Louis I. Kahn. The address had been deliberately scratched out.

For three days, the body lay unclaimed in the city morgue. Eventually, someone figured out that Louis I. Kahn, the mystery corpse, was actually the Louis Kahn, one of the 20th century’s giants of architecture. The New York Times put the story on Page 1 the following day.

Louis Kahn’s undignified death in March 1974, at age 73, was in keeping with a professional and personal life that was remarkably off kilter, even by the often quirky standards of the design trade.

Kahn’s output was modest compared to other big names in the field. He never designed a commercial building. His best buildings came in a decade late in life. Several major projects were never built, victims of his notorious fussiness and client budget limits. A bitter feud with Philadelphia’s urban planning boss effectively blacklisted Kahn for large projects in his hometown. His domestic life was unconventional, to put it mildly. He was pathetic with money and his firm was perpetually on the financial brink. He died broke.

But oh, the successes. The Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla. The Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, and two art museums at Yale. The library at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. And Kahn’s final masterpiece, albeit off the beaten track, the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Each a “must see” on anyone’s short list of modern architectural marvels.

These, and other built and unbuilt projects from Kahn’s drawing board, plus drawings, paintings and intriguing objects from his professional life, are on display at the Bellevue Arts Museum (BAM). It’s the first retrospective of Kahn’s work in 20 years and it confirms, if confirmation were needed, why Kahn is worshipped by architects, past and present.

Frank Gehry is one of Kahn’s acolytes. The swooping, computer-generated curves in Gehry’s buildings, like Seattle’s Experience Music Project Museum, seem light-years removed from the grounded designs that flowed from Kahn’s drawing board, but Gehry, in a short video at the Kahn show, gives proper credit: “My first work came out of my reverence for him.”

Born in 1901 in Baltic Russia (now Estonia), Kahn came to the U.S. with his parents as a young boy and settled in Philadelphia, where he lived his entire life. At the University of Pennsylvania, his talent as an artist morphed into a love of architecture.

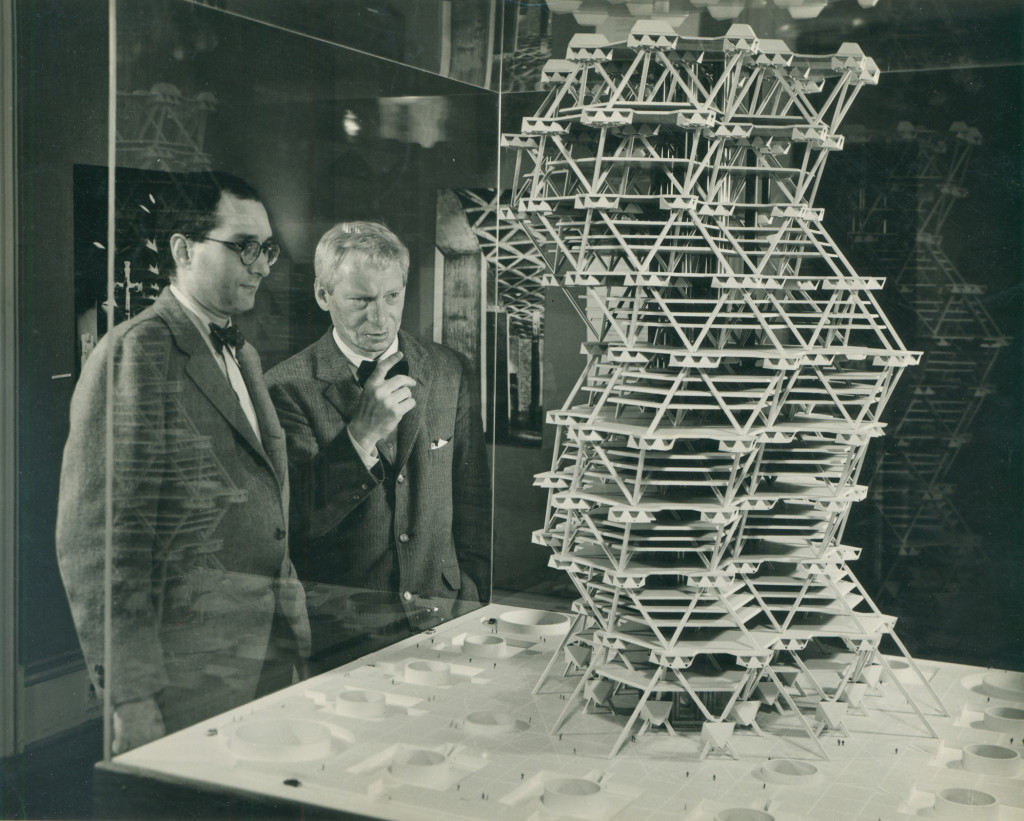

Early on, he designed houses and several public housing projects. Intrigued by the novel construction principles in Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome, Kahn and colleague Anne Tyng designed a 540-foot twisting City Tower for municipal workers in center city Philadelphia. A 12-foot model of the tower dominates the BAM show. The real thing was never built.

Neither were massive cylindrical parking garages that Kahn wanted to place on the downtown perimeter, making center city Philadelphia largely pedestrian. All of Kahn’s urban planning ideas, some of them clearly utopian, were shot down by Edmund Bacon, executive director of the city planning commission -- and the father of actor Kevin Bacon. Bacon’s blueprint for reshaping Philadelphia made him nationally famous and put him on the cover of Time magazine. The two men, each with a Type A ego, clashed. Bacon won.

"It would have been an incredible tragedy if they had built one single thing Lou recommended for downtown Philadelphia,” said a self-satisfied Bacon, years later. "They were all brutal, totally insensitive, totally impractical."

A fellowship at the American Academy of Rome came just in time. Always a traveler, Kahn discovered a spiritual link in ancient structures. Grecian temples. The French walled city of Carcassonne. His excitement at first seeing the Egyptian pyramids jumps off a postcard he sent to Anne Tyng at the home office: “No pictures can show their monumental impact. They are any color you want them to be.”

A large 18th century print of Piranesi’s proposed plan for Rome’s Campo Marzio was added visual inspiration for an architect reaching back in time. It hung for years on a wall in Kahn’s office and is hanging these days on a wall at BAM.

The more Kahn travelled, the more he retreated into antiquity, out of step with peers like Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. The modernists were fixated on airy buildings with glass walls. Kahn’s designs had thick slabs and huge circular cutouts. Spaces were painstakingly arranged to capture and modulate outside light. Brick and exposed concrete were his favored materials.

In a word, Kahn was designing modern buildings that looked timeless. “Ruins in reverse” is a favorite Kahnism.

In 1959, Jonas Salk, developer of the polio vaccine, asked Kahn to design a research institute on a prime 27-acre Pacific Ocean shoreline site in La Jolla, outside San Diego. “Create a facility worthy of a visit by Picasso,” Salk told Kahn. Mission accomplished.

A symmetrical series of poured concrete ”study towers,” with walls pivoted 45 degrees, provide space for large open labs and windows with spectacular ocean views. One wonders how any research gets done. The towers flank a long rectangular courtyard, bare except for a thin rill stretching toward the blue Pacific. Kahn wanted a garden between the buildings but noted Mexican architect Luis Barragán convinced him to keep the plaza bare except for the water feature. Give Kahn credit for knowing a great idea when he heard it.

In Fort Worth, Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum resembles a half dozen horizontal farm silos, stacked together. A clever skylight system diffuses the burning Texas sun into a lush interior glow in the barrel vault galleries. An ideal environment for Rembrandt, Michelangelo and other masterpieces from the Kimbell's collection. In the eyes of some critics, it's the 20th century’s most revered museum.

It’s impossible to consider Kahn and ignore his bizarre domestic life, an aspect barely mentioned in the BAM show. Kahn was married for 44 years to Esther Israeli. Subsequently, he had romantic relationships with two women, his professional colleague Anne Tyng, and Harriet Pattison, a landscape architect who played a major role in the Kimbell's site design. Pattison also collaborated with Kahn on Franklin Delano Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park at the tip of Roosevelt Island in New York City's East River.

Each of these three woman had a child with Kahn at widely spaced intervals. The relationships were barely acknowledged by the adults and the three children didn’t know the other two existed until after Kahn’s death.

This odd arrangement is explored in My Architect, a widely praised documentary film by Nathaniel Kahn, Pattison’s son and the youngest of the three children. In the film, Tyng and Pattison speak poignantly about their conflicted relationships with Kahn. Esther Kahn refused to talk. In a heart-wrenching moment, Nathaniel, who was 11 years old when his father died, meets his two older half-sisters in a house designed by their father. They discuss what it means to be a family.

Nathaniel also visits several of his father’s buildings and talks with Kahn's colleagues. My Architect was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary in 2003. Said New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp: “I have never seen or read a more penetrating account of the inner life of an architect, or of architecture itself, than that presented in this movie.”

My Architect is virtual prerequisite for anyone attending the BAM show. BAM screened it once last month with Nathaniel Kahn in attendance. Not showing it regularly during the exhibit seems like a lost opportunity. Fortunately, you can watch it free online.

The BAM show’s final gallery highlights Khan’s most complex project, Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Bangladesh’s national parliament building. Film shot by Nathaniel Kahn contrasts Dhaka’s urban ruckus — overcrowded buses, noisy tuk-tuks, helter-skelter river boat traffic — with the silence and order that the parliament house seems to command. A lone woman in a purple sari sweeps a broad flight of steps with a broom. A handful of young men do coordinated calisthenics in the shade of the parliament walls.

A panoramic view shows a portion of the monumental government complex sitting placidly in a reflective man-made pond. Is the building waterlogged and sinking — an appropriate image for a sea-level country where vast numbers are regularly drowned in floods and cyclones, and for a national economy that struggles mightily just to stay above water? Or does it symbolize the hope of a desperately poor country on the upswing, a government rising from the water like an aquatic phoenix?

Maybe both.

Inside, it is quiet. A handful of parliamentarians do the people’s business. And worshippers bow toward Mecca in a large prayer room. Kahn, a secular Jew, threw all his efforts at the end of his life into designing the governmental centerpiece for an Islamic nation with a major space in that complex dedicated to daily Muslim prayer.

The Dhaka complex took 23 years to complete. Khan never saw it. It was finished in 1983, nine years after his death.

A scene in My Architect captures the impact. Shamsul Wares, a Bangladeshi architect, says the parliament complex was an impossible dream for his country. Kahn was “not a political man but he's given us the institution for democracy from where we can rise,” Wares says.

“He wanted to be Moses here. He gave us democracy.”

Louis Kahn: The Power of Architecture, is at The Bellevue Arts Museum until May 1. It travels to the San Diego Museum of Art in November and to the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth in March, 2017. The show was organized by the Vitra Design Museum in Weil Am Rhein, Germany.