This is the fifth in a special series about the forgotten history of Nazis in the Northwest. The series starts here.

Fritz Wiedemann is “probably the most dangerous Nazi in the country."

-- Look Magazine, December 1940

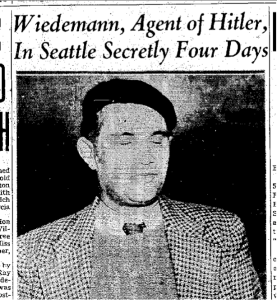

In early December, 1940, an athletically built man in a boldly patterned brown tweed jacket and a beret bolted out the door of a restaurant on Marion Street in Seattle and strode up toward Fourth Avenue, pursued by a Seattle Times photographer. Finally, told he’d be the subject of a newspaper story, he stopped midway up the steep hill, turned and agreed to be photographed.

“You American newspapermen are very smart, aren’t you?” he said. “You always find out the things right away, don’t you? I like that.”

He clearly didn’t.

His name was Fritz Wiedemann, and he was the German consul general posted to San Francisco. He had been in Seattle secretly for at least four days staying at the Olympic Hotel. When a diplomatic big-wig came to town it was often news, but Wiedemann was here under the radar. Even his wife back in California didn’t know where he was.

Questioned by a reporter, Wiedemann was vague about why he was in town. Just minutes before, he had been speaking to a group of some two dozen German American Seattleites at their weekly get-together at the informal German Roundtable at Maison Blanc, more commonly called Blanc’s café, a well-known continental restaurant of the era housed in an old mansion. No one would tell the reporter what was discussed over lunch.

The Times story described Wiedemann as “Adolph Hitler’s West Coast ‘mystery man,’” and while the reporter was able to ferret out little about his visit, the fact that the press was dogging him was an indication of growing scrutiny of the Nazi activity on the West Coast.

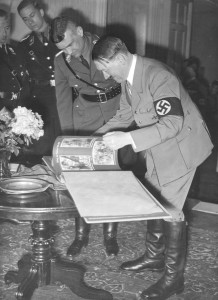

Captain Fritz Wiedemann had spent years on Hitler’s staff as his personal military adjutant. He had worked for Rudolph Hess as well. He had been Hitler’s superior officer in WWI and reputedly saved the future Fuhrer’s life by pulling him out of the rubble of a collapsed building under heavy bombardment. Wiedemann had become a trusted personal emissary of Hitler’s, sent to England for the coronation of George VI, then to the U.S. on a secret mission. He had marched into Prague with Hitler in 1939. Shortly afterward, he was appointed the Nazi’s main man on the West Coast. Look magazine wrote that he was “probably the most dangerous Nazi in the country.”

According to author Clint Richmond, who has studied the German’s West Coast intelligence network of the era, it was considered “highly significant than an official of such status in Hitler’s inner circle would be shuffled off to the outpost at [San Francisco], just a few months before Germany launched total war in Europe — unless, of course, the Nazis considered the position of huge strategic importance in the joint German-Japanese spy operation against the Americans.”

In December, 1940, World War II — the “total war in Europe” was well underway: The Nazis had conquered Poland, Norway, France, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands and other countries. The Battle of Britain was going full bore. Japan was expanding its empire in Asia. The world was going up in flames and here was one of Hitler’s inner circle hobnobbing with local businessmen during a secret visit to Seattle .

By many accounts, Wiedemann was a charming man, said to speak English without an accent. He was often described as a playboy, although he was married. He appeared in the San Francisco society columns, had a son in a Bay Area school and owned a villa in a prosperous community outside the city. He put a more friendly social face on the Third Reich than his immediate predecessor, Baron Manfred von Killinger, who had stirred up and defended the militant pro-Nazi German American Bund.

Still, the Bund was active in Seattle, even if shunned. In 1939, two University of Washington students, working as government informants, had infiltrated the Seattle Bund, ferreting out its source of anti-Semitic propaganda, pamphlets that came directly from Germany. They reported to the Congressional Dies Committee, which focused on subversive activity, that their contact was a local agent of the Hamburg America steamship line. They said they were assigned to spread the material among the UW student body and heckle a Jewish professor. They also revealed that two Bund members, Harry Lechner and Paul Stoll, were employed at the Boeing aircraft plant. Not coincidentally, 1939 was a year when the FBI was charged by the president with internal security. They began to watch local German American activities more closely.

Wiedemann publicly said he disapproved of the Bund. As with the Nazis, however, things were otherwise. After the war, newspaper reports said that the FBI had learned that Wiedemann and the head of the West Coast Bund, Hermann Schwinn — who had spoken in Seattle on more than one occasion — had plotted to assassinate King George VI and Queen Elizabeth during their visit to the U.S. in 1939, though no attempt was made.

Even more complicating, Wiedemann might have been playing a double game. After the war, it came out that around the time he visited Seattle, the consul general had been feeding selected information to British Intelligence, and there were rumors that he was part of a movement against Hitler. Did Wiedemann have second thoughts about the man he’d saved during the first war?

Yet he was still facilitating the German espionage network. In March, 1941, a German agent had been greeted and sheltered by Wiedemann at the San Francisco consulate on his return from the Pacific. He was killed a couple of weeks later in New York. In his possession were detailed sketches of defense installations at Pearl Harbor, which would be attacked later that year.

Wiedemann was not the only German charmer to come through town. A man named Dr. Herbert Mehlhorn and his traveling companion, Werner Heydenreuter, made an unheralded visit in the summer of 1938. Mehlhorn was described as a policeman, Heydenreuter as a sports coach. They were allegedly on a hunting trip to Canada and Alaska. Seattle’s German consul at the time, Gustav Reichel, put them in touch with a prominent German American, Dr. Carl S. Leede, who had met Mehlhorn previously on a trip to Germany and had had “a pleasant chat with him” at Gestapo headquarters. Leede introduced them to other German Americans, took them sailing on Lake Washington, to dinners at Seattle Tennis Club and Blanc’s Cafe, and on a trip to Mt. Rainier.

Records show that both men — and Wiedemann too, for that matter — were winners of a special, much- coveted gold sports medal given for athletic prowess to members of the Nazis' elite SS. Melhorn had worked with Manfred von Killinger on the Nazi takeover of Saxony and with Heinrich Himmler. Gestapo man Mehlhorn also joined the foreign office as a member of the SD, the Nazis’ security service, and was given travel assignments to gather intelligence. He later played a key role in the invasion of Poland. As a high-ranking SS officer, he is said to have won a medal for his role in exterminating Jews there.

As war intensified in Europe and conflict between the United States and Japan in the Pacific crept closer, such friendly gatherings grew rarer. The German consular office in Seattle closed in 1939, and in July 1941, the U.S. expelled all German diplomats, according to the Associated Press, “on the grounds that they had engaged in activities inimical to the welfare of the United States.” Wiedemann was unceremoniously shipped out of the country. He spent much of the rest of the war posted in China.

That marked the end of the days of the Third Reich trying to win hearts and minds.

Next: What became of the Northwest's Nazis, and Nazi sympathizers?