This is the third in a special series about the forgotten history of Nazis in the Northwest. The series starts here.

“If anybody doesn’t like the way Hitler does things, he can go plumb to hell.”

— West Coast German American Bund leader Hermann Schwinn, Seattle, 1937

As the 1930s progressed, the Germans carried out multi-pronged diplomatic and propaganda efforts on the West Coast. In Seattle, the new consul, Dr. Gustav Reichel, continued local efforts to forge ties with the German American community, participate in public events, and socialize with the city’s elite.

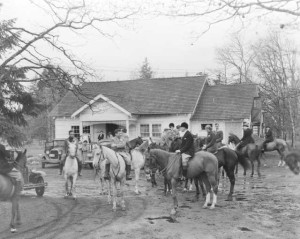

Reichel was a horseman, a former WWI cavalryman with diplomatic experience at The Hague and in New York. His social schedule included participating in Tea Dances at the Seattle Tennis Club, attending Soroptimist fundraisers, competing in horse shows at the Olympic Riding & Driving Club in North Seattle, and riding to hounds with fellow equestrians at the Woodbrook Hunt Club south of Tacoma.

He also encouraged business and trade ties with Germany. “One development which we all want is the enlargement of the markets for the products of the Pacific Northwest, which include, of course, your fruit, lumber and fish,” he said in the Seattle Times. Like many other local businesses, the consul even took out ads in the paper wishing the citizens of Seattle a Happy New Year from the German consulate.

But while Reichel enjoyed the good life in the Northwest, events were playing out down south that would test Americans’ patience for the Nazis and their sympathizers living on the West Coast.

In 1937, Baron Manfred von Killinger took over as Reichel’s boss in San Francisco. If German foreign service veterans like Walther Reinhardt and Reichel put a skillful diplomatic face on the Third Reich, von Killinger embodied Nazi thuggery and his appointment thoroughly alarmed anti-fascists, Jews and the American government.

His resume was appalling. Von Killinger had operated anti-Communist and anti-Semitic death squads in Germany after WWI. He was involved in the assassination of a prominent German politician, became a Nazi stormtrooper, and was later made prime minister of Saxony during the Nazi takeover of local governments. He was a Nazi member of the Reichstag and alleged to be involved in its arson. He even boasted of his brutality. In a memoir published before WWII he recounted whipping a naked 19-year-old woman in the streets “until no white spot remained on her back.” When asked by reporters about it, he likened it to “spanking a naughty child.”

Von Killinger was no Nazi apologist — he embodied every aspect of the Nazi regime that instilled fear and loathing. His appointment as consul-general in San Francisco, responsible for the Western U.S. from Canada to Mexico, raised alarms. A New York Congressman, Emanuel Celler, said “In von Killinger, Hitler has given San Francisco a Nazi agent gifted in spreading vicious propaganda against Jews, Catholics, Protestants and all who abide by the principles of our American Democracy.”

The American Legion questioned von Killinger’s appointment, issuing a statement that said in part, “Is it pertinent to ask: Does a strong desire for technical knowledge about the United States Pacific fleet have anything to do with the appointment of von Killinger now that Germany’s ally in the Orient is on a rampage?” In 1937, Japan had invaded China, launching a brutal war.

The FBI concluded that von Killinger’s main purpose was to ramp up Nazi spying efforts. According to author Clint Richmond in his book about Nazi espionage in the West, “Fetch the Devil: The Sierra Diablo Murders and Nazi Espionage in America,” von Killinger was indeed sent to San Francisco to take charge of and invigorate the already existing, clandestine Nazi spy network in the western United States. “Von Killinger had neither the grace nor tact generally required of a diplomat and was thus immediately unpopular in the business community he was supposed to charm.”

Indeed,Von Killinger's skills were precisely the opposite. According to Richmond, the FBI concluded that he was the ‘“most ruthless' of consular spies sent to the U.S.”

During von Killinger’s tenure, the German American Bund grew into a large force. Huge pro-Nazi rallies were held in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and the Seattle branch expanded. It was later discovered, after Pearl Harbor, that at least three members of the Seattle Bund worked for Boeing or Boeing contractors.

One Bund event held in Seattle in November of 1937 proved very controversial.

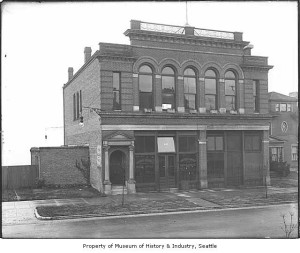

The German-speaking community has a hall on First Hill at 9th and James, German House, which has played host to many cultural and social events by local German and Swiss groups. That November, Western Bund leader Hermann Schwinn returned to Seattle to hold a rally there, billed as an anti-Communist speech.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer described the scene: “While two Nazi flags were held as sentinels, an urgent plan for all German Americans to rally against communism was held. … Lighted candles in groups of three flickered as speakers preceding Schwinn addressed the audience in German. At one point in the program, two stalwart men wearing white shirts with dark armbands raised the Nazi flags on the platform while the audience gave the Nazi salute and sang in German.”

According to the Jewish Transcript, German consul Reichel was in attendance, along with some 75 other people. Calling Schwinn “the No. 1 preacher of Jew-hate” in the West, the Transcript reported that he denounced a recent Franklin Roosevelt speech against dictatorship and cried out in German, “If anybody doesn’t like the way Hitler does things, he can go plumb to hell.”

This came at a time when the city and Mayor John F. Dore were attempting to crack down on local Communists by banning their meetings from venues such as Civic Auditorium. The head of the Washington Commonwealth Federation, Howard Costigan (secretly a Communist Party member), said that some German American organizations in Seattle were engaged in pro-Nazi activities and accused Mayor Dore of “un-American activities” for forbidding meetings of a recognized party, the Communist Party, while allowing Bund activities like the one at German House.

Outraged by the scene at German House, two members of the Seattle City Council, Hugh DeLacy — later a Congressman and also a secret Communist party member — and David Levine, sponsored a resolution to investigate German House with an eye toward revoking its dance hall license. The resolution stated “if permitted to flourish, Nazi principles will result in civic, racial and religious discord and endanger the peace of the community…”

In a letter to the council, the German House’s president, E.E. Mittelstadt, claimed the hall was rented “without our knowledge of the purpose of the meeting.” The statement seems incredible: Mittelstadt had acknowledged previously that allowing the meeting to be held had sparked a behind-the-scenes fight within the German House. Some in the German community objected to the Bund using their facility. Hermann Schwinn and the Bund were well known on the West Coast and Schwinn had previously spoken about the “new” Germany in Seattle. The consul’s attendance seemed to put an official seal of approval on the rally.

The city council dropped the idea to revoke German House’s license after the club executives pledged “as loyal American citizens … [to] not knowingly rent our premises to any individual or organization for the purpose of anti-American propaganda be that Communist, Nazi or Fascist.”

To emphasize the raised stakes, in the fall of ’38 someone pumped three bullets into the club, which a spokesman attributed to “some anti-Nazi fanatic.”

Von Killinger’s Bund boosterism, meanwhile, had attracted the scrutiny of Congress’s so-called Dies Committee, named after Rep. Martin Dies, whose panel was investigating “un-American activities.” After a number of public controversies, Von Killinger was recalled to Germany, then went on to become the de-facto Nazi leader of Axis ally Romania where he was charged with implementing the Final Solution. He killed himself as the Soviets advanced in 1944.

Americans, it seemed, were tiring of propaganda campaigns, once subtle and now more boisterous. The Seattle Star newspaper editorialized on the German House dust-up and the debate over Communist meetings, saying that it was against all “isms,” be it Communism, Nazism or Americanism. “Propaganda is just another form of military invasion,” the paper said.

Subsequent events proved that such “invasions” weren’t over, and that real ones, here and elsewhere, were a growing possibility.