The landscape is squishy with memory for me, like a soggy sponge or bed of moss. Memories ooze when I step onto familiar ground. Two intersections from my South Seattle past offer contrasting glimpses of what I experience as I move through the city.

One is South McClellan Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Way (formerly Empire Way), in the Rainier Valley. I lived just a few blocks away. There used to be a couple of service stations, a shoe repair shop and a small diner there. The Italian barbershop we patronized was nearby.

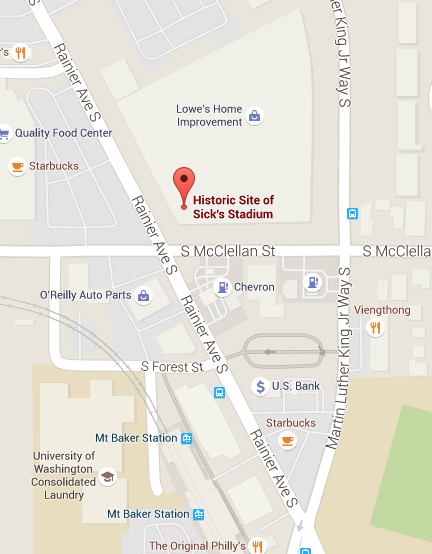

What’s now the backside of a Lowe’s hardware store was formerly the site of two of Seattle’s most historic baseball stadiums: Dugdale Field, followed by Sick’s Stadium. Dugdale was the home of the Seattle Indians and Giants baseball teams. It burned down in 1932; Sick’s replaced it and became the home of the Pacific Coast League Rainiers and, briefly, the major league Pilots.

In my youth, Sick’s was my field of dreams, the place where my father and I went to enjoy a game—me by watching it, my dad by drinking Rainier beer under the grandstands. That seemed to work for us, if he left me with enough Cracker Jack to while away the innings.

Sick’s brought excitement to the neighborhood. Elvis played a concert there, as did Jimi Hendrix, and in 1970 I watched Janis Joplin perform from my viewpoint on Cheapskate Hill, a steep bank along Martin Luther King Jr. Way that once allowed an unobstructed view of the field over the outfield fence for those who wouldn’t or couldn’t pay admission.

The Rainiers were the only baseball team we had for many years. I remember attending opening day of the Pilots in 1969 and later seeing teams of legend, like the New York Yankees. Speaking of the Yankees, one thing I learned later was that Babe Ruth played an exhibition game at Dugdale back in the day and hit a home run so far that it left the stadium and bounced across McClellan. Babe Ruth, in my neighborhood!

The intersection is poised for change, with transit-oriented development slated around the nearby Mount Baker light rail station. The area around Lowe’s will become high-rises. I think it’ll be good for the valley. My memories, however, aren’t going anywhere.

The second intersection of memory is 23rd Avenue South and South Jackson Street, a onetime trouble spot in the Central District, known for crime. What sticks in my mind is a painful visit there one night in 1968. My elderly grandmother, a wonderful Scottish lady who never learned to drive, took the bus downtown for shopping as she did most days. She was one of those women who always seemed to be lugging a bag of things she’d picked up at the once great and now gone Frederick & Nelson department store. We were never sure why, but she got off the No. 10 bus alone at 23rd and Jackson, and subsequently was mugged by some punks. She refused to give up her precious handbag — that large, heavy purse, with few real valuables in it, was her life — and she was dragged down the street, and shaken, dazed and traumatized. She had few memories of the incident, but massive bruises told part of the story.

When he heard from the police, my enraged father took me with him down to 23rd and Jackson to find witnesses, a foolish thing to do at the time. At age 14, I was no real bodyguard. On one corner was a pool hall. We entered. The proprietor sat on a high bench — like a judge’s bench — so he could view the room. The place went silent when we entered. My father pleaded, and then, with barely concealed anger, asked for the proprietor’s help in identifying the young men who did the deed.

He stonewalled us. Guys at a nearby pool table snickered and sneered, then laughed as we left. No one was ever caught or punished, to my knowledge. My granny was at the tipping point of dementia and she nosedived afterward and had to be put into a nursing home. She died the next year.

A portion of the title of one of Jamie Ford’s Seattle novels, “on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet,” seems to apply here. If my memories of McClellan and Martin Luther King Jr. Way lean toward sweet, those of 23rd and Jackson still have the flavor of the bitter, leavened by seeing a neighborhood that seems safer and more welcoming now than it was in those rough times.

The city is a collection of personal landmarks that cannot be protected by law, nor can they be demolished until death or senility. The city is a living fabric, a place of deep personal significance and layered meaning for many of us.

This article originally appeared in the January issue of Seattle Magazine.