The issue of living and work space for artists in Seattle isn’t going away soon, though the artists themselves might very well. As a Seattle-based artist who goes rather far away fairly often to work, I find the situation of how artists are faring in many places increasingly sad. The problem of urbanization driving out artists is present here in Mumbai, India where I have been at work for the past couple months.

I’ve been living and working in South Mumbai in a warehouse (godown), because I was here in Bombay (as those in the art world still like to refer to the renamed city) for an exhibition last year. Invited back to do a larger installation this month, I came back early to build the work in-situ.

Real-estate prices and rentals are notoriously expensive in this city of close to 20 million, with too much demand and not enough supply. So I asked a couple of Bombay curator friends where I might find affordable studio and living space. They both suggested an artist residency in Mazagaon, long ago a fashionable area, now certainly not, but nicely within hailing distance of the city center, near the docks in amidst rows of many other godowns.

The space is funky, very raw and spare. With a bit of outfitting, mainly draping with old patterned cloth, courtesy of several fabulous outdoor markets, it’s all quite workable. I got the proprietor to clean up the “communal” kitchen, which apparently no other visiting artist has used, and I’m all set.

There are many contiguous warehouse spaces in the complex, owned and operated by the father of the woman who cares for and feeds the artist residency. He bought the complex in the early 1970s and ran it for a number of years as refrigerated storage. He told me that energy costs made doing that today too expensive, but I suspect that as with all port cities nearly everywhere, actual perishable goods coming off ships is the least of what’s being stored, moved and traded in Mumbai.

Still, the residency is a small part of a much larger operation. Lorries, small trucks, hand-carts and men on foot with all sorts of cargo on their heads come and go, off-loading and picking up goods warehoused in the other spaces. The entire compound is completely surrounded by high masonry walls.

On the front of the complex slide two massive steel gates, hung off the masonry wall, letting godown traffic in and out, and nearby is the gatehouse where the gatemen sit, sleep and meticulously check everyone in and out. On the street side of the wall, built right up to the edges of the gates, runs a straight line of shacks or “shanties,” as they are called here, that continues for at least a kilometer, being attached to other godown walls as they continue their march towards the docks.

The shacks are all two-story, with a ladder on the outside, about 6 feet deep and about that high in each story, and share common plywood/scrap wood walls with their neighbors. For the inundation of the monsoon season, they are often covered with blue tarps. Inside, and spilling out in front where cooking, eating, sleeping, washing up and much socializing happens, are extended Bangladeshi families.

There are other Bangladeshi settlements in Mazagaon, as well as other such ethnic enclaves in other parts of this rambling city. In an echo of the talk one could easily hear on the Republican campaign trail (if not so much in Seattle) or right here in Mumbai from the far right Shiv Sena, I was told several times when I arrived that my neighbors came here “illegally,” that they were all thieves, that their women never worked etc. From what I’ve been able to gather, hiring help to sneak through the India-Bangladesh border is pretty easy and pretty cheap, and therefore the flow of Bangladeshis seeking economic opportunity continues unabated.

The city authorities seem in no hurry to evict them, probably because they (male and female) do much of the work that nobody else wishes to take on. A water line runs along the wall, the squatters are allowed an hour each day of open taps. Electricity is also somehow available. Each house has a couple big blue “carboys,” blue barrels that once held chemicals, now repurposed to hold water. The city provides washing and toilet facilities nearby in small buildings run and staffed for that purpose.

On Sundays, there’s a long line at the wash-up centers for cleaning oneself up for another busy week. During the day I see few Bangladeshi men here — I’m told many work somewhere away from the shanties doing intricate embroidery for expensive wedding saris, others do basic construction work, and back of the house restaurant work. On Sunday and in the evenings, the men are back and hanging out with their families. Though eating happens late in Mumbai, the ladies begin cooking before dark in front of their shanties, so that they can still see what they’re doing.

The shanty life hovers somewhere between homelessness and serious poverty. But the plywood shacks provide a modicum of privacy and, even within such confined space, some storage. The women, when they aren’t out working, do lots of wash, scrubbing clothes on the pavement for a washboard, and the kids, who play with discarded objects like plastic water bottles in the street, are mostly cleanly clothed. Like kids anywhere they are full of laughter and kinetic energy.

Like the kids, Mumbai is full of frenetic activity, and seems on the edge of chaos all the time except perhaps a couple hours just before dawn. As raw as the godown space is, it’s quiet and peaceful and ridiculously safe. Safe because inside the walled compound in a large open yard are stored dozens of Audi cars. The Audi is the current car to be seen in here: It has cache, style, costs a fortune and is about twice the size of everything else on the road. The guards are here to protect them. Most of the cars are white (which makes sense in this tropic climate), most are SUVs (which decidedly doesn’t since the traffic in Mumbai barely moves and there is very little space on the roads) and most all are TDIs, a type of diesel that Audi and Volkswagen long claimed was extremely good for the environment.

It’s not clear to me how much the current VW/Audi diesel scandal is of concern here. Perhaps there has long been a backlog of TDI Audis sitting in lots in South Mumbai. But certainly it is true that the cars warehoused here are far more problematically illegal and questionable than the poor Bangladeshi. The fraudulent “clean diesel” Audis are contributing straight away to the city’s intractable air pollution.

While the automaker phonied up its vehicles’ environmental credentials, the families camped on the other side of the wall might or might not have legitimate paper work. But either way, they produce a net gain for the city. They are not on a public dole. And I have read in The Hindu that there has yet to be a case where an “illegal” Bangladeshi in Mumbai has been charged with committing crimes. All this notwithstanding, Audis are foreign with much “export quality” status and the Bangladeshi are foreigners with no status at all.

Recently, the father who owns the complex, and who sits in his air-conditioned office in the compound every afternoon reading the newspaper, tells me that in a matter of months, the Audis will be joined by Amazon. When he first told me about this, he said he knew nothing about this Amazon except that it was a “billion dollar company.” Whatever, the company, expressed interest in renting his many godowns in the complex for warehousing products. He assures me that the artist residency and his office will remain separate from the new corporate presence.

One of the tantalizing things about Mumbai is that it seems everything and anything is available somewhere and somehow. It’s an artist’s dream — a seeming endless cornucopia of stuff spills out of doorways onto sidewalks literally everywhere — stuff of every description, of every conceivable color, size shape and pattern. This is tangible, three-dimensional stuff, not Photoshopped photographs of on-line merchandise.

But one of the things that is in extremely short supply here is affordable artist workspace, which is rarer still on a short-term basis. The arrival of such entities as Audi and Amazon out in the boondocks of Mumbai is surely very pleasing to the likes of the gentleman who owns the godowns where I write this. But it certainly portends a future where, despite the owner’s assurances about this spot, artists are squeezed spatially and economically even more, as they seem to be most everywhere where there is a thriving urban culture.

The conundrum facing a megacity like Mumbai, and the much younger and smaller Seattle, is despite their differences, the same. Both places tout their cultural richness, but the swirling piles of money displace the artists every time. Artists are by necessity and temperament ahead of the curve. This is good, because their only salvation may be to look for a place to work in a city that isn’t thriving. The conundrum for artists, apparently world-wide, is that while it’ s stimulating to live and work in a place that says it supports the arts, an actually much more supportable life may very well be had in a place that has either fallen off the list, or never gotten on it.

As if to underline the situation, I was sneaking out of Mumbai for a few days in Calcutta, long the undisputed cultural center of India, and now left behind in the booming dust of Mumbai, Bangalore and Delhi. Awaiting our departure in the shiny new Mumbai airport, we were bracketed by two huge hoardings (billboards), hanging inside the hall. One was for Amazon, the other for Audi.

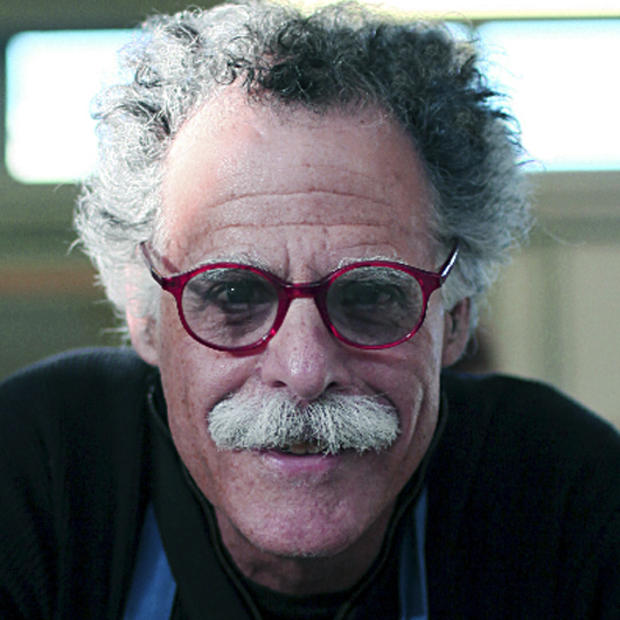

You might also be interested in Don Fels' article from last June: "Revive Seattle's creative spirit by inciting cultural trouble. " Fels has just opened an installation, Turning Blue, at Bombay’s Clark House Initiative that deals with and expands upon the subject of two of his articles from Crosscut last fall, "Dangerous colors and the poisoning of the Spokane River" and "What will it take to clean up a poisoned river?"