It’s a homecoming of sorts for the Trisha Brown Dance Company as it returns to Washington next week for its final stage performances. It was in coastal, small-town Aberdeen that Trisha Brown grew up in the 1940s and 50s with the shore and rainforest as her playground.

The University of Washington’s World Series at Meany Hall will present the stage performances by TBDC from Feb. 4-6 and as part of a community-wide retrospective of choreographer Trisha Brown’s large artistic legacy. The month-long celebration also includes a photographic exhibit at Meany Hall and a film screening on February 19 at the Henry Art Gallery.

Trisha Brown’s name has become synonymous in the U.S. and abroad with postmodern dance, which postulated that anyone could be a dancer and any subject a dance. After attending Mills College in Oakland and teaching at Reed College in Oregon, Brown headed to New York City in the early '60s, where an exciting critical mass of performing and visual artists were collaborating.

Diane Madden, co-artistic director of the company since Brown’s retirement in 2013, says of Brown, “She was a pioneer in SoHo.” Madden’s statement, playing off the choreographer’s Western roots, also resonates with Brown’s choreographic approaches and the work she made. She integrated New York’s landscape — its buildings and parks into her site-specific work. A couple of site-specific pieces will be mounted in Seattle for the retrospective next week.

Brown helped usher in the postmodern era in American dance performance as part of an artistic collective called the Judson Dance Group, which presented its work at the Judson Memorial Church in New York’s Greenwich Village. Brown and her cohorts were the avante-garde in dance of the time, rejecting the theatricality of their predecessors, such as Martha Graham. Their performances were often about ordinary, everyday subjects, at the same time that Andy Warhol was making art inspired by Campbell’s soup cans and Robert Rauschenberg, a long-time collaborator of Brown, turned a bed into a canvas.

In 1970, Brown founded her eponymous, New York-based company and would work with her group for over 40 years, creating roughly 100 works during her career. The company has sustained critical acclaim, especially in the U.S. and France, since then.

Brown is perhaps best known for embracing spatial and time structures that form the basis of a dance. For example, in her “accumulation” pieces, she created rules for the accumulation of dance movements, revealing that pattern could provide the basis of a dance, just as it had in visual art. If these dances sound brainy, they are: One could see the concentration in Brown’s face as she performed them. She was also the first woman choreographer to receive the MacArthur Foundation Fellowship “genius award.”

Regarding the importance of structure in the choreographer’s work, Madden says, “As important as play is in Trisha’s process, it can’t exist without a ‘steel’ structure…that allows for a great deal of space for the dancer to fulfill the choreography.” Madden mentioned that each of the four pieces presented as part of the final stage performances at Meany – PRESENT TENSE (2003), Son Gone Fishin’ (1981), Rogues (2011) and You can see us (1994) -- has a different structure. You can see us was also Brown’s last collaboration with Robert Rauschenberg.

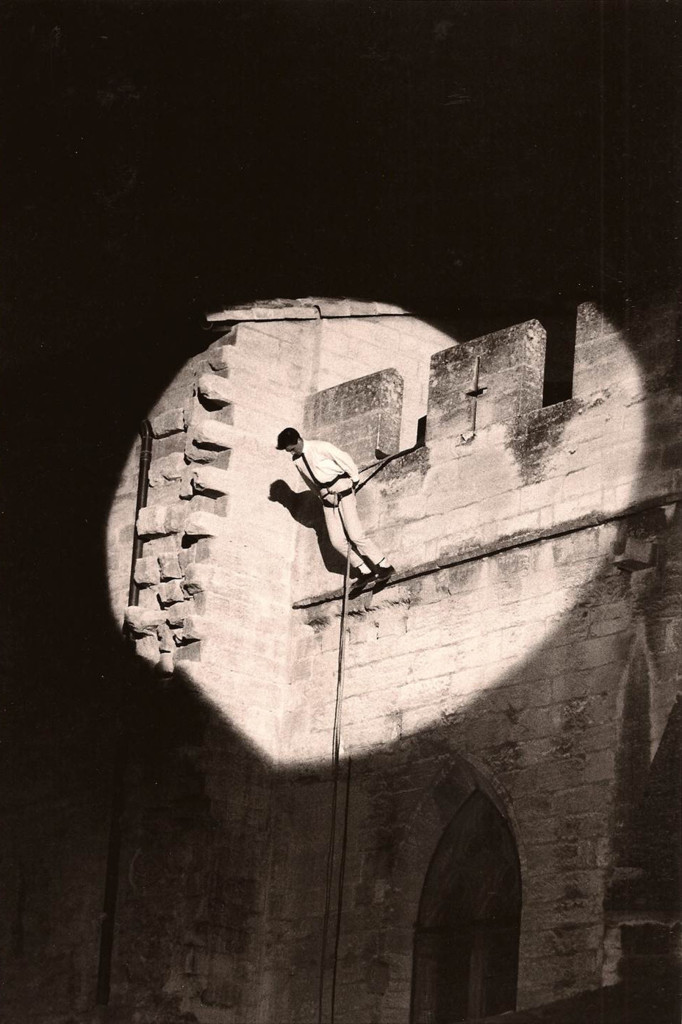

As part of UW’s celebration, lecturer Rachel Lincoln, from aerial dance group Bandaloop, will reconstruct Brown’s 1970 piece, Man Walking down the Side of a Building. The title is a literal description of the piece. In it, a harnessed performer turns pedestrian movement on its side to stunning, gravity-defying effect; Lincoln will walk from the top of Meany Hall’s exterior to its bottom. At SAM, TBDC will present another site-specific work, Trisha Brown: In Plain Site, referencing the proximity between performers and audience that dancing in a museum affords. Choreography for this piece will come from Brown’s vast repertory.

Brown retired three years ago in her mid-seventies for health reasons, just as the proscenium tour was getting underway. (The tour is closing this weekend at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.) The company’s board named Madden and Carolyn Lucas as Brown’s artistic successors. Following their Seattle stage performances, the company will turn its focus to educational initiatives and setting site-specific work.

Madden says that it’s not an ending. True to a choreographer for whom structure was paramount, Brown’s legacy will live on, just in a different form.