Signs of Seattle's continued boom can be seen across the city. Cranes stand over the rising concrete frames of skyscrapers in Denny Triangle. Across the Pike/Pine corridor, modern apartments are nearing completion behind their historic brick facades. And just off of commercial strips all over the city, townhouses and small apartment buildings nudge neighborhoods from their suburban past to their urban future. So 2015 construction figures will likely come as a surprise to many: housing production is actually set to decline this year as compared to the year before.

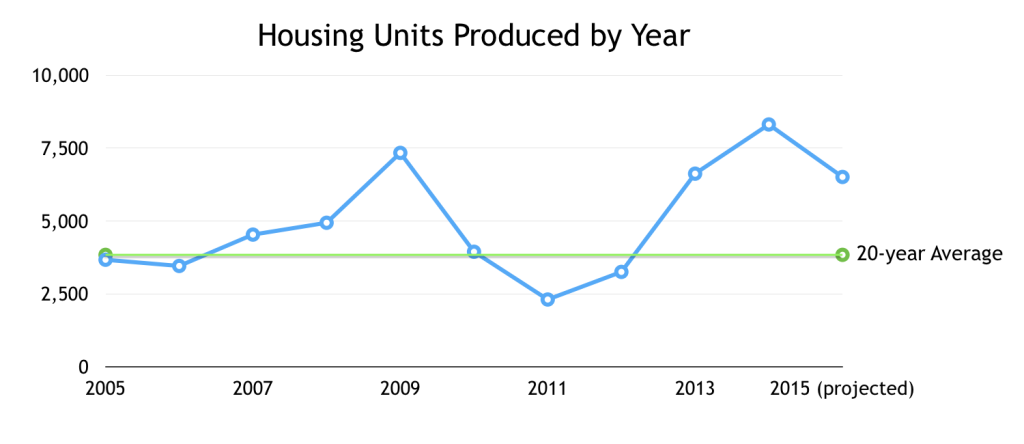

Housing production took a dive from 2009 to 2011 because of the recession, but bounced back just as quickly. Extrapolating from numbers published by the City of Seattle for the first three quarters of 2015, housing production for this year will be about 6,800 units (although an end of the year surge is certainly possible). That's about equal to 2013 levels, but off significantly from the 8,300 units produced in 2014.

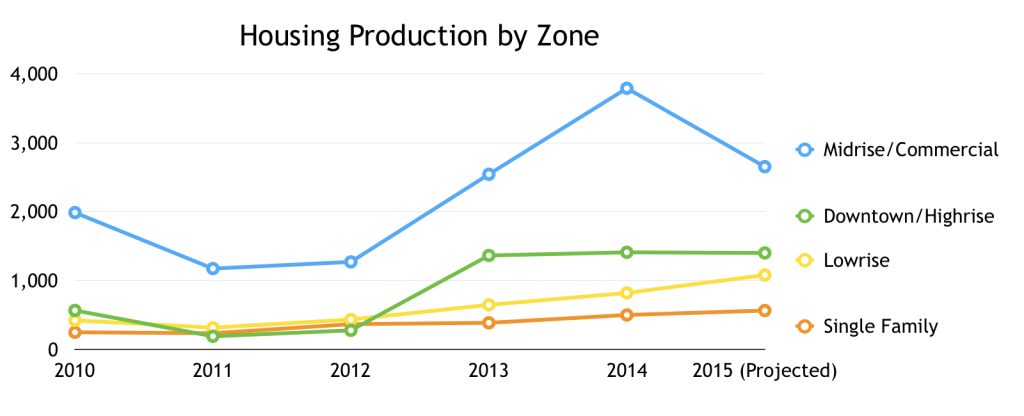

If you find it hard to believe that construction has slowed, that might be attributed to where you live and what kinds of construction you pay attention to. Production of single family homes, townhouses and small apartments is up by over 20 percent – single family homes specifically are up 13 percent. These projects also accounted for fully 75 percent of the roughly 600 housing units to be demolished this year, which goes a long way towards explaining the general sense that Seattle's small scale residential neighborhoods are changing rapidly.

But these production increases in lower density neighborhoods were more than offset by a sharp decline in midrise construction—the 6 to 8 story large apartment buildings that now characterize neighborhoods like South Lake Union, Ballard or the Pike/Pine corridor. Housing production from these projects dropped from about 3,800 units last year to a projected 2,700 units this year.

These trends also vary greatly by neighborhood (see City of Seattle's report). Large apartment projects can have two or three hundred units, so the completion of a single project in one year versus another can sway the neighborhood level statistics significantly. Bucking the city-wide trends, we saw production continue to accelerate in Capitol Hill, First Hill, the U-District and Columbia City. The Pike/Pine corridor in Capitol Hill is a notable example, with five large projects (Ava, Pike Motorworks, the Broadstone, Cue and Evolve) collectively adding almost a thousand units of housing to a few square blocks.

On the other hand, South Lake Union, Northgate, Queen Anne, Ballard, Green Lake and Roosevelt all had a paucity of big projects reaching completion compared to 2014. South Lake Union had the most notable decline. 2013 and 2014 each saw the opening of five or six large apartment projects. This year there's only been a single big project completed, the 118 unit AMLI apartments.

This doesn't necessarily represent a fundamental slowdown, however. There's a huge amount of housing still in the works for South Lake Union. 2015 in South Lake Union is probably best seen as a statistical blip of calm before the storm: 15 large apartment projects totaling almost 4,000 units are already approved in the neighborhood and another 19 projects totaling 6,000 units are going through permitting (as covered in an earlier story on South Lake Union).

This year's decline in mid-rise construction likely points to a shift in where our new housing comes from.

Midrise has been the dominant force over the last five years, accounting for almost half of the net housing production. But the neighborhood centers where six to eight story construction is permitted may be reaching saturation. Going forward, a wave of high-rise construction in downtown, Denny Triangle and South Lake Union is perfectly timed to take its place. There are currently 32 towers of at least 13 stories permitted, and another 40 in the application stage. Together they would encompass 20,000 units of housing, although not every one of them is likely to be built.

The seven or eight thousand units produced each year should be kept in context with the City's projection of 120,000 new residents moving to Seattle over the next 20 years. New construction is inevitably expensive, and highrise towers even more so. But without significant new housing, the vast number of new residents—and newly wealthy residents thanks to the tech industry—are certain to push out ever more low income residents.