This is the second of a two-part series about color, chemistry, and how global commerce and weak federal regulations have led to the poisoning of the Spokane River. Read Part 1 here.

A Seattle-based artist, I’ve been delving into the world of Indian-made blues, colors manufactured in the subcontinent, for a couple of years, research for an upcoming art installation at the Clark House Institute in Mumbai. I was shocked to find that the blues made in India, and yellows made in China, were in part responsible for the high levels of cancer-causing PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) the Spokane River. The chemicals, contained in ink on paper being recycled at Spokane’s Inland Empire Paper mill, were seeping into the river.

There is, it turns out, a connection in this case between India, the Spokane River, and the first peoples of the Northwest.

The Spokane Indian Reservation was created in 1881 by executive order of President Rutherford B. Hayes. At just under 160,000 acres, it is a fraction of the 3 million acres the natives inhabited before the reservation was created, but is still fed by the Spokane River, which has traditionally fed the Spokanes with salmon.

Salmon represent 80 percent of the diet of the Spokanes, but in 1995 the Spokane Tribe unequivocally demonstrated that the Spokane River salmon had dangerous PCB concentration in their tissue. As a 2014 letter to the EPA from the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, co-signed by the Spokanes, states:

Water and salmon are among our tribal First Foods. They are first in serving order during our longhouse ceremonies. Our people eat up to nine times as much fish as the ‘average’ non-Indian. Fish consumption is part of our religion, culture and way of life. The risks to tribal peoples, other fish consumers, and the environment from PCBs far outweighs any possible ‘economic considerations.’

The centrality of salmon to the life and livelihood of the Spokane Tribe moved the Washington Department of Ecology to adopt the country’s strictest permissible amount of allowable PCBs for the Spokane River. The standards, measured in parts per quadrillion, are so strict that it is technically impossible to measure for such a minute level of contamination, let alone attain that level of purity. One of my interviewees likened finding errant chemicals at that level to finding one leaf in the entire landmass of the United States.

But the state’s water quality standard has been trumped by, of all things, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

I’ve asked the EPA directly: if PCBs are leaching into the Spokane River from pigments that contain PCBs, why aren’t they banned? PCBs are, after all, one of the most widely studied contaminants in the world. They have long been known as potent carcinogens. They accumulate in ecosystems and in the bodies of animals (like fish) and humans. Children are particularly at risk because they get exposed to higher concentrations relative to their body weight, and they metabolize the chemicals more quickly. Such accumulation in kids has been shown to create serious physical disease as well as very troubling cognitive dysfunction

I’ve asked the EPA directly: if PCBs are leaching into the Spokane River from pigments that contain PCBs, why aren’t they banned? PCBs are, after all, one of the most widely studied contaminants in the world. They have long been known as potent carcinogens. They accumulate in ecosystems and in the bodies of animals (like fish) and humans. Children are particularly at risk because they get exposed to higher concentrations relative to their body weight, and they metabolize the chemicals more quickly. Such accumulation in kids has been shown to create serious physical disease as well as very troubling cognitive dysfunction

The agency’s reply to me included the statement that, “an exception is made for inadvertently generated PCBs that are unintentional impurities of many common commercial chemical or manufacturing processes. EPA has concluded that allowing such inadvertent generation has important economic benefits and does not pose an unreasonable risk to human health or the environment.”

In July, Judge Barbara Rothstein ordered the Environmental Protection Agency and Washington State Department of Ecology to set limits on the discharge of PCBs into the Spokane River. In its required response to the judge, the agency says that the PCBs are not being manufactured in the pigments, but are present as an unintended consequence (which somehow makes them less to be feared than those ‘intentionally’ put there), and that besides, banning their use in pigments would create problems in the marketplace. What paint would we put down for yellow stripes on highways? What ink would we use in our home printers for cyan?

What the EPA actually seems to be telling us all is that a great deal of political pressure has been put on the agency by the chemical industry to allow PCBs in pigments, because to disallow their inclusion would add manufacturing expense.

In a 2010 letter to the EPA, the Color Pigments Manufacturing Association stated that taking CuPc or phthalo pigments off the market would jeopardize color printing, the vast majority of blue and green paint, as well as many plastic formulations. According to industry spokespeople, we’d be left with a discolored, or even uncolored world. They go as far as to insist that we would all be transported back to the black and white days of my childhood and the presentation of the world in print without color. They also say that it is infeasible to alter manufacturing processes to exclude PCBs from the phthalo colors.

It isn’t. As I explained in the first story in this series, phthalo pigments contain PCBs because using chlorine-based solvents was the easiest and the cheapest way to manufacture the color. When the trichloro benzene solvent reacts with the other chemicals in the color manufacturing process it creates a chemical reaction and PCBs are produced.

But I have spoken with, and examined the product specs of, major pigment manufacturers based in Mumbai that no longer use chlorine-based solvent to produce the color. They produce and export PCB-free CuPc blue. Just a few years ago the cost of replacing the trichloro benzene solvent with alkyl benzene (which produces no PCBs) increased the final production cost of the pigment by 5 percent. But enough companies are now using the alkyl-based solvent that the price has dropped precipitously. Producing CuPc without PCBs is no longer a cost issue.

Interestingly, in 1989, a similar drama played out on the shores of the Spokane River. The residents of the tiny Liberty Lake Sewer and Water District, which drains into the Spokane River, were chagrined by the large amount of algae blooming in the river. Research established a major culprit to be phosphates in laundry detergents. People in the community began boycotting such detergents, which in turn led to bans of phosphates around the country. By 1993, all laundry detergents sold in the United Sates were required to be phosphate-free.

Interestingly, in 1989, a similar drama played out on the shores of the Spokane River. The residents of the tiny Liberty Lake Sewer and Water District, which drains into the Spokane River, were chagrined by the large amount of algae blooming in the river. Research established a major culprit to be phosphates in laundry detergents. People in the community began boycotting such detergents, which in turn led to bans of phosphates around the country. By 1993, all laundry detergents sold in the United Sates were required to be phosphate-free.

A decade ago, a new battle heated up around Liberty Lake: The Sewer and Water Commission was considering banning phosphates in automatic dishwasher detergent, just as it had in laundry detergent. In 2005, well aware of what had happened with washing machine detergents, mighty Proctor and Gamble sent representatives from Cincinnati to Liberty Lake to testify before the commission. The company claimed that without phosphates, dishes wouldn’t come clean, and anyway, they’d be covered with spots.

Liberty Lake banned phosphate-containing dishwasher detergents anyway. The State of Washington followed and, again, so did most of the rest of the country. Just last year, P&G announced that it will no longer put phosphates in any of its laundry detergents, wherever they’re sold. Proctor and Gamble cited company research in developing phosphate substitutes for the new and improved laundry detergent.

Could something similar happen with PCBs in pigments?

Judge Rothstein ruled in March that the EPA and Washington Department of Ecology erred in allowing the Spokane River Regional Toxics Task Force to be set up to address the issue of reducing PCBs in the Spokane River, instead of simply mandating a clear time-table for their removal. The ruling is yet another strange irony in the story of colors polluting the river. In fact, by far the most lasting legacy of the 1974 Spokane Expo has been the public-private collaboration that it established around cleaning-up the river. Sixty years on, the task force is the latest promising iteration of a cooperative effort to save the river.

Decades of regulatory effort have shown that neither the EPA nor Department of Ecology can clean out the PCBs getting into the Spokane River fish gills, because there is no science yet available to accomplish such a task. Gov. Inslee said as much in his speech on the matter last week. What must be done instead is to find ways to keep the PCBs from getting into the river in the first place. This will apparently require a groundswell, not unlike those initiated by Liberty Lake, to swamp the vested interests that guide public policy in our region, and in our country.

In the case of inexpensively produced pigments, patterns of consumption will have to change: We are going to have to live without the cheapest colors, and demand that they be banned from commerce.

The chemical industry is going to have to modify pigment formulas, and experience in the Pacific Northwest has shown that collaborative cooperative efforts can make the change happen. It is obvious that it will take such effort to move the EPA to do the right thing.

The Inland Empire Recycling Paper Mill wants to continue in operation, which, if the EPA pushes its water quality standards, it will not be able to do. The production of paper with 60 percent recycled fiber is the green thing to do. But it is not, nor has it ever been, enough. We consumers need to rethink our responsibility to such things as clean water beyond the act of tossing our used paper in the recycle bin.

Color is by nature, design, and use, distracting. Dressing up goods or walls or embellishing printed matter, it can make everything look and even feel like class acts, even when they aren’t. The application of color is the easiest, and usually the cheapest way to get us to buy. But cheap doesn’t mean not costly; pollution and disease are very expensive.

Color is by nature, design, and use, distracting. Dressing up goods or walls or embellishing printed matter, it can make everything look and even feel like class acts, even when they aren’t. The application of color is the easiest, and usually the cheapest way to get us to buy. But cheap doesn’t mean not costly; pollution and disease are very expensive.

Blue is in fact the color of water and the sky, a universal sign of their purity, and one of the reasons that the color has long been a favorite of artists, and polling shows, everyone else as well. But because blue never appears ready-to-use in nature (even the indigo plant required a great amount of very messy and polluting processing to render the color useable), it has always been costly, one way or the other. For centuries its cost was synonymous with its special value, and the color was reserved for such treasured roles as the depiction of the Virgin Mary’s cloak in Medieval paintings. At that time, color-fast blue was only obtainable from Afghanistan, in the form of lapis lazuli, a rare mineral that once processed became ultramarine blue. The fact that the blue we most use now comes to us from equally far away in India disappears in the rotation of our global marketplace.

But as the cost of a poisoned Spokane River illustrates, its still ultimately extremely expensive stuff. To my mind, the problem of PCBs moving from pigment colors into fish is not one of unintended consequences at all, but rather one of un-tended consequences. It is known how and why this is happening. For the practice to stop, people with responsibility will have to tend directly to the problem. That would be us.

In researching this story the author is very grateful for generous help provided by: Adriane Borgias, Spokane Water Quality Lead, WA State Dept of Ecology, Brian Crossley, Water Program Manager, Spokane Tribe, Elizabeth Grossman, science writer, Mark MacIntyre, Senior Communications Officer, EPA-Region 10, Priyam Jhaveri, CEO, NaNavati Group, Mumbai, Doug Krapas, Environmental Manager, Inland Empire Paper Company, Michael LaScuola, Technical Advisor, Environmental Health, Spokane Regional Health District, Chris Page, Ruckelshaus Center, facilitator for the Spokane River Regional Toxics Task Force, Dr. Sheela Sathyanarayana, Chair, United States EPA Children’s Health Protection Advisory Committee. They are of course not responsible for any factual errors in the story.

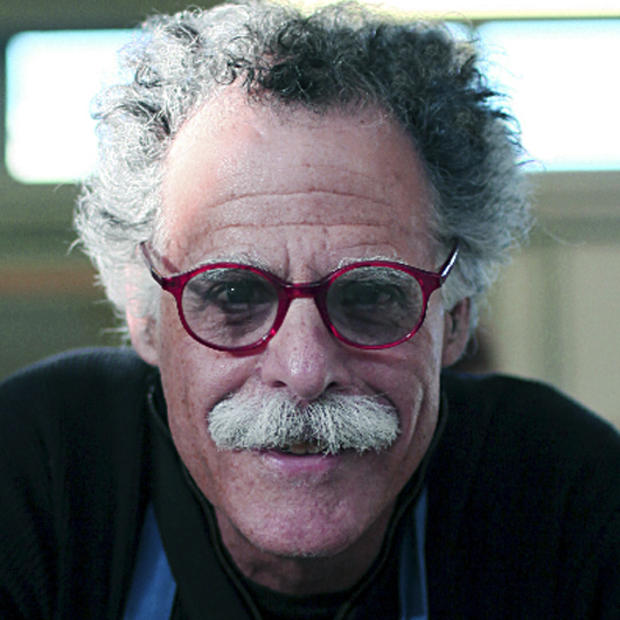

Don Fels is a visual artist who has worked around the world since the 1970s following the trade in commodities. He has researched and created art on two other Northwest rivers, the Duwamish and the Willamette. Rivers have always been major elements in trade networks. He finds the confluence of connections inherent in those networks, and how they play out in place, rich for art-making.