In March, U.S. District Court Judge Barbara Rothstein ordered the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Washington State Department of Ecology to set limits on the discharge of PCBs, well known carcinogens, into the Spokane River. In July, the EPA responded with a revised river clean-up plan. Then, last week, Gov. Jay Inslee released new state water quality standards that allow for the continued discharge of PCBs into the river.

This is the first of a two-part series about color, chemistry, and how global commerce and weak federal regulations continue to sicken the Spokane River.

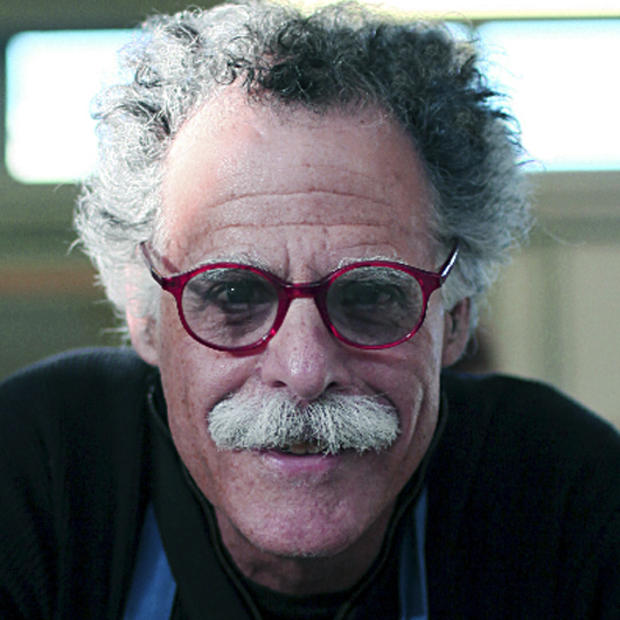

I became a visual artist because I’ve never been able to resist color’s pull. I was a kid in the ’50s. My family got a TV when I was in 5th grade. Life magazine came to the house weekly, and the LA Times daily. All were unquestionably in black and white, as if there were no other way of portraying reality. Yet outside and all around, the world was brightly colored. I found those colors outrageously appealing, and have ever since.

Today, pretty much everything arrives everywhere in glowing color. But centuries before color came to electronic devices, publications and everyday objects, producing it was one of the world’s largest trades, as it continues to be. In centuries past, to get a hold of color meant mounting a fleet of sailing ships and sending them around the world, where strains of natural colors (animal, mineral and vegetable) resided in far-flung, usually tropical places -- a massive undertaking that often set in motion large-scale death and destruction. Most of the world’s largest chemical companies began as color manufacturers.

Color is essential to today’s manufacturing, and to the marketing of that which is made. It can be incredibly sublime or outrageously in-your-face. Either way, color continues to come with a price, from places usually hidden far from view.

But artists work to make the invisible visible, and I became fascinated by the notion of making art about the world of global trade, finding ways to uncover the layers, trajectories and overlaps inherent in such networks. That has meant immersing myself in what are called commodity chains -- the global linkages that deliver resources from far afield into our personal lives.

That’s how I came to realize how colors’ production today has created a complex set of troubles for people living and working in Spokane and Eastern Washington that has seemingly tied well-meaning business, state, federal and tribal leaders in knots.

When I stumbled on the connection between colors and pollution in the Spokane River, I was knee-deep in research for an art installation in Mumbai.

India is without doubt one of the most brightly colored places in the world. The streets are covered with all manner and scale of signage ablaze with color, buildings painted incredible colors. Even the tiniest object for sale is packaged in the brightest colors obtainable. And Indians love very colorful clothing. Color offers people in India and everywhere else, regardless of their economic status, a way to shine, a way to project their sense of power and wellbeing out into the world.

Perhaps not surprisingly, India has led the world in producing the most used and desired color -- blue. For several centuries, India was the primary source of indigo, which in fact is named for the country. The color blue, occurring very rarely in nature, has always been highly in demand throughout the world, not the least for uniforms, military and otherwise -- blue jeans being the ‘uniform’ with which we are most familiar. The British, having colonized India, withdrew huge profits from the subcontinent for a long period by shipping dried indigo cakes, made with great, very difficult labor from the processed indigo plants, to Europe for fabric dyeing and printing.

In the middle of the 19th century, with the British Empire at its zenith, the Germans, with no colonies and therefore little access to exotic natural resources, began imagining replacements for what they couldn’t get in Northern Europe. In the 1880s, after a decade of expensive experimentation, the German chemical company BASF patented synthetic indigo, using nascent organic chemistry (then based on coal-tar) to produce a color that was chemically identical to that which came from the indigo plant, at a fraction of the cost. Slowly but surely, the Germans put the British/Indian plant-based indigo trade out of business.

A century after the crash in the trade of natural indigo, color is no longer bound to place by what grows or is sourced where. Ironically, however, it is still very much geographically bound by other factors. Phthalo (pronounced thay-low) blue, also known as copper phthalocyanine or CuPc, the world’s most-used color, is produced almost entirely in India, from petroleum-based chemicals. The azos, another set of synthetic colors -- reds, oranges and yellows -- come predominately from China. Thus, India and China now control the primary colors.

One of the many factors that led to the world’s color being produced in Asia was weaker environmental control there. Making colors often released nasty chemicals into the air and water. Though colors are not, and have never been, manufactured along the Spokane River, they have been found to be befouling the river in a dangerous way.

The falls of the Spokane River, the site of the founding of the city of Spokane, was once also the site of an enormously rich fishery, where natives easily caught all the salmon that they needed to sustain themselves. By the 1960s, however, the fishery was barely existent, the river having long before become an open sewer, into which drained the city’s toilets, industrial waste from large upstream mines in Idaho, and from nearer plants like the Inland Empire Paper Company and Kaiser Aluminum.

Then Spokane was chosen as the site of the 1974 World’s Fair, thanks in large part to Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson, often called the progenitor of the Environmental Protection Agency. Spokane Expo ’74, billed itself as “Celebrating Tomorrow’s Fresh New Environment.” The World’s Fair was held in the smallest city to have ever hosted the fair, seemingly because it was the first to take on the theme of environmentalism.

The eco-fair didn’t result in a cleaned up river for Spokane, but it did create momentum to rid the area around the falls of a huge unsightly tangle of railroad tracks, to create a large park making the river and the falls once again the jewel of downtown, and to set in motion the creation of a state-of-the-art sewage treatment facility. Perhaps most importantly, the Expo inspired the creation of the Spokane River Drainage Basin Depollution Policy Committee, a working partnership of civic, municipal and private entities that met regularly to work up solutions to the river’s impurity.

Four decades after the fair, however, the fish in the Spokane River are laced with PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), commercial production of which was banned in the U.S. decades ago, shortly after the fair closed.

The pollution of the river is of course not due to a single factor. But one of the contributing causes is now known: In 1991, at a cost of tens of millions of dollars, the Inland Empire Paper Company, located on the banks of the Spokane River, completely modernized, thus becoming the sixth mill in the country that produced recycled paper. Company owners were doing what they saw as the right thing, for greening the environment and for their growth as a company: In the late 1980s, California, one of the company’s primary markets, had begun legislating that paper would need to contain a high percentage of recycled content.

Not long before the mill began producing recycled paper, its effluent was thoroughly tested, and found to be PCB-free. Some years later, when PCBs turned up in the tissue of the river’s fish, the mill’s waste-stream was tested again, as was the outflow from all the city’s treatment plants and other ‘legacy’ industrial sites on the river. IEP was shocked to find that by operating its brand-new, seemingly exceedingly ‘green,’ high-tech facility, it was discharging PCBs into the Spokane River.

The plant was not making PCBs, but it was passing them through to the river; they were hiding in the (recycled) material it used to make paper. Specifically, they were in the colors.

Phthalo blue, discovered in Scotland in the mid-1930s, is among the newest of the colors available on the world market, and was hailed almost immediately as an ‘ideal’ even ‘perfect’ blue. It is bright, clear, with unbeatable color strength, it’s terrifically color-fast, heat and chemical resistant, non-toxic to users, works very well as a dye with all substrates and all manner of cloth, and also works excellently as a pigment for ink.

The cyan that we all know from refilling our color printers, is phthalo blue. Phthalo blue is also frequently used as a colorant in plastics (the ubiquitous blue tarps, though made in China, are colored with the Indian-made pigment) and paints.

But phthalo blue can contain PCBs, as can the azo yellows, oranges and reds. Most ironically for this particular story, sales of phthalo green pigments continue to increase each year because a great deal of consumer packaging now proclaims (in the same color ink) that the product enclosed therein is “green.” Phthalo green pigments can contain even more PCBs than the blue.

The IEP plant recycles publications printed with phthalo blue and green, and azo yellows, oranges and reds. As part of turning printed matter into clean white paper, those inks, and their pigments, get washed away. After the wastewater is thoroughly treated, it is flushed into the river, taking the PCBs with them. And it is perfectly legal.

This is happening because, athough the EPA banned PCBs that “could have unintended consequences in humans” (i.e. cancer), the agency allows the importation of products that contain PCBs as an unintended consequence of their manufacture -- that is, when the PCBs are not themselves the chemical for sale.

Since the discovery of PCBs issuing from the mill, the mill owners, who themselves also publish a printed newspaper, the Spokesman-Review, have installed the best available post-production waste-treatment equipment in an effort to remove the PCBs from the flow. But it’s simply not enough; the PCBs resist the treatment, and continue to be stored in the river’s fish.

As Portland-based science writer Elizabeth Grossman succinctly puts it, “PCBs do not occur naturally, and once they are in the environment, they can last for decades.” The persistence of PCBs has long been known to industry, a quality that once made them highly desirable. PCBs were sought after because they added tenacious chemical stability to products, protecting them from breaking down.

In essence, what made PCBs seem very good, ultimately makes them very bad: they are persistent in the environment, and are, as a result, an intransigent problem to remove. They don’t easily go away. The PCBs from recycled paper aren’t the only ones showing up in the Spokane River fish, but very troublesomely, despite seemingly best practices, they continue to do so.