https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpiaeI1Eez0

When we first meet Marty, the impudent slacker in director Joel Potrykus’ film Buzzard, the impression he makes suggests we’re about to see a film we’ve seen before: another rude, jokey portrait of an unappealing loser. Marty is running a little scam on the bank where he works, closing out his checking account and then immediately opening a new one to score the $50 signing bonus the bank is offering. Marty’s face, long and bug-eyed, is captured in one unbroken, five-minute shot, his sour expression barely concealing his disdain for the system he is gaming.

Even though we might admire Marty's petulant audacity, we also want to slap him. The scene, which slowly sinks its talons into you, sets the unsettling tone of Buzzard, a surprisingly compelling and often brilliantly original independent film. By the time it’s over, whatever skepticism you brought to the movie has been torn to shreds.

Director Potrykus composes his film with an eerie calm. Most of the sequences are single takes. They slowly build to an atmosphere of queasy menace, before cutting abruptly to blackouts. Some of the scenes are sandblasted with screaming thrash metal, some play out with a generic background hum. Others stare back at us like hallucinations. All feature Marty and his misanthropic scowl.

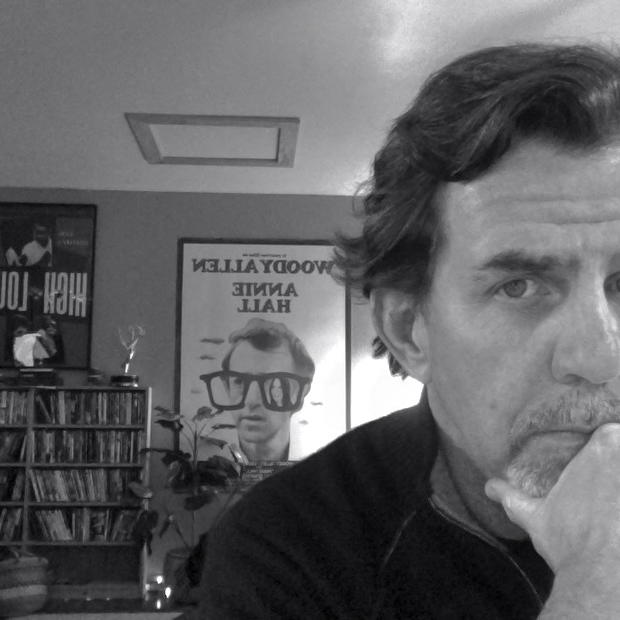

Played with uncompromising fury by Joshua Burge (above), Marty is both smart and dumb. In addition to his petty – but entirely legal – checking account scheme, he also orders unwanted office products on the company dime and then returns them to pocket the refund. Eventually he starts cashing checks meant for the bank’s customers, a fraudulent practice Marty classifies as just another way he is sticking it to The Man.

His only friend appears to be Derek, an annoyingly nerdy workmate who is fixated on video games (and played by the director with intense, off-kilter enthusiasm). Derek and Marty chug Mountain Dew like it’s beer. They insult and taunt each other. Their friendship, ironically, seems built on mutual, poisonous dislike. When Marty discovers the checks he’s been cashing can be easily traced, he flees his apartment and holes up at Derek’s, a brief respite that tips Marty’s bitterness towards violence.

Consumed by paranoia, and faced with the knowledge that, except for minor scams he’s mastered to bring in a few easy bucks, Marty realizes he has no idea how the world really works. His naiveté has doomed the one thing he prizes the most: his freedom. He rages at his own stupidity and, in phone calls home to a mother we suspect he hasn’t seen in years, Marty seems depleted by sadness.

Against all odds, Marty has triggered our sympathy. This is where Buzzard achieves the unexpected, where what began as a portrait of an asshole transforms into a portrait of a lost soul, albeit one without much of a heart.

Burge and Potrykus work hand-in-hand in creating scenes that are by turns gross and transfixing. Marty is obsessed with the Freddy Krueger character and has fashioned a glove with razors for fingers, which becomes a convenient weapon. He dons a hideous devil mask while listening to abrasive music in his room, and wakes up in a movie theater in an even more terrifying mask. The image is startling, like something from a nightmare.

In another scene, again shot in one long, excruciating take, Burge devours a plate of spaghetti in real time, overstuffing his mouth as noodles spill down the front of his bathrobe. Somehow this scene, which should simply be repulsive, is riveting, suggesting this man-child’s feeble upbringing and his profound disinterest in the rules of conventional life. As Marty’s bleak options narrow, he is granted the possibility of escape. But in the movie’s final, astonishing shot, an abstract slice of screen trickery, he seems to have spawned a doppelganger, one that chases him to his fate.

This review first appeared on The Restless Critic blog.