Not long before the Seattle vote on preschool options, Marcy Whitebook, Director and Senior Researcher at the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment (CSCCE) at University of California, Berkeley, was in town for a meeting with the Gates Foundation. The foundation had recently commissioned her to write a paper comparing ECE and K-12 personnel systems.

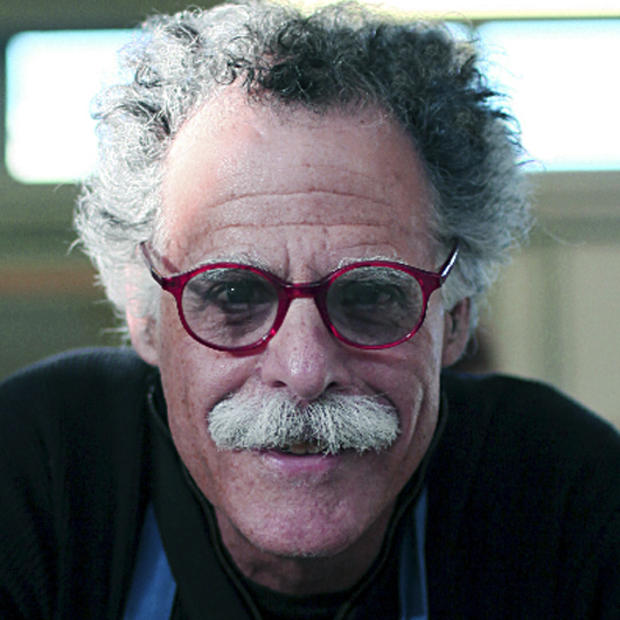

Friends since high school, we arranged to have dinner at the market during her visit. Whitebook established the CSCCE 15 years ago and has directed its efforts toward researching and getting action on better funding to prepare, support and reward early childhood educators. It is her strong and deeply informed belief that without decent pay for preschool teachers, high quality preschool for all children cannot be realized.

The subject of creating quality early childhood education for all is now much in the news, nationally and locally. Shortly after we met in Seattle, President Obama announced a billion dollar investment in early childhood education. That effort will phase in a continuum of programs for children between birth and age 5. In his recent State of the Union address, Obama called on Congress to bring high quality preschool to every American child.

The discussion (which many would argue should have happened decades ago), is now a very public one. However, the details in implementing such a focus on the youngest years, which are not much mentioned, matter a great deal. It was for this reason that I wanted to speak with Whitebook.

Alongside my career as a visual artist, I spent many years working as a preschool teacher, and as a teacher of teachers. Over thirty years ago I proposed to Boeing that they institute an in-house preschool. They found the idea completely inappropriate. But things have changed, and in light of the November election and the mandate to provide universal preschool in Seattle, I interviewed Dr. Whitebook. What follows is an edited version of our discussion.

How come you decided to tackle the issue of early childhood educator pay?

As a recent college graduate, I chose a career as a nursery school teacher. I was enthralled by witnessing and facilitating how young children learned. But it quickly became apparent that there was something amiss — many parents could not find or afford good services, only some teachers had access to education and training, only a handful of programs paid a decent wage and I witnessed one skilled fellow teacher after another leave to pursue a career that offered greater respect and reward.

So a handful of my fellow teachers and I set out to expand and improve child care and specifically to secure the rights, raises and respect for the early childhood workforce that would allow us to provide what children and families needed and deserved. We were young, fired up and convinced that taking care of children means taking care of their teachers. Or, as has been our mantra since those early days, “the quality of care children receive is directly linked to the education and training, working conditions and pay of their caregivers.”

Now years later, how does the early childhood education landscape look to you?

While the jobs remain low-paying, our expectations for early childhood teachers have soared enormously as we have learned more about brain development and early learning. The work of teaching young children is highly skilled and complex.

Can you quantify the pay situation for early childhood education teachers?

Teachers’ salaries in K-12 ranked in the middle for all occupations in the U.S in 2013, according to the U.S. Department of Labor, while early childhood teachers as a whole rank at the bottom. Pre-K teachers are ranked higher than child care teachers — and have made some movement upward over the last fifteen years in some states — but still fall below the 20th percentile of all occupations in terms of salary. Child care teachers — those most likely to work with our babies and toddlers — remain solidly at the very bottom of the salary ladder, ranking nearly at the bottom percentile among over 1,000 occupations in 2013.

As was true a quarter of century ago, the educational pay premium for early childhood teachers is miniscule. Early Childhood Education teachers with B.A. degrees earn, on average, half the amount of comparably educated women and one-third comparably educated men in the workforce.

There is a basic flaw in how we currently finance early childhood services, as parents themselves are very stressed by the high cost of care, so the solution cannot rest with families. Great disparities exist not just with larger society but according to age of children served and the setting in which you work---they determine pay rather than qualifications.

Besides the basic ethics and essential ‘fairness’ (we shall return to this term in a bit), why do you view better pay for early childhood education people as so important?

We know that that the low pay for early childhood education teachers makes it difficult to attract and retain educated and skilled teachers and fuels turnover, which is damaging for children and inhibits quality improvement efforts. Many skilled women employed to teach and care for our babies, toddlers and preschoolers live with enormous economic stress, due in large measure to these low wages. As a consequence, many — especially those with young children — utilize public income supports, such as food stamps, despite working full-time.

And how do you think that such uncertainty and stress effects the work that the educators do and the care that the young children receive?

The skills necessary for effective teaching require teachers to be observing and making assessments about what each child needs and could be learning at every moment of the day. They need analytic and organizational skills, as well as knowledge of child development and teaching strategies, all much harder to do when one is worried or stressed. Our most recent study, Worthy Work, STILL Unlivable Wages explored the link between higher levels of teacher worry about their economic well-being and lower program quality.

I’d like to play the devil’s advocate a bit here. Certainly anyone thinking about the financial or even emotional health of early childhood education teachers would wish them security and serenity. But assuming such a state of affairs, what guarantee is there that qualified and far-seeing persons would seek such employment?

Or put another way: Can you imagine a future time where those who care for the very young would actually have the status of university professors? After all, a great quantity of research has established that early brain development is key to most emotional and intellectual strength, and future success in the world.

There are powerful forces working against such a transformation in the educational system, not the least of which is the political climate, which works against making the necessary level of investment in early childhood education. Our social norms about work involving caregiving keep the status low, and we haven’t made much progress in valuing so-called women’s work.

Valuing early childhood education teaching requires a concerted effort to raise awareness about the complexity of working with young children along with improving the status and pay of teachers across the age-span.

It is maddening to read about college students not being able to find work that utilizes their education at the same time there is a pressing need for college-educated teachers to work with young children.

The Seattle ballot issue mandates a fair wage for Early Childhood Education. How would you recommend that figure be arrived at? Can it be set up right off the bat? Should it be worked up to?

If fair is not defined in the ballot language, it could be interpreted in a number of ways: Fair compared to other early childhood education teachers doing similar work? Fair meaning parity with other teachers working with older children?

Some public Pre-K programs have paid Pre-K teachers the same starting wage as K-12 teachers, but do not include provisions for moving up the pay scale based on experience and professional development. The research evidence about the strongest programs for children points to parity with K-12 teachers. Why not build it in from the start, if our goal is to attract and retain highly skilled teachers who can provide high quality early learning experiences?