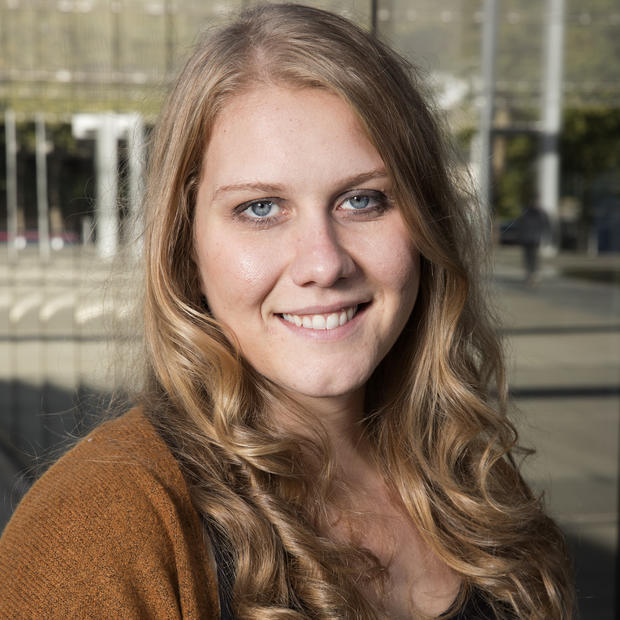

Several years ago, Zoe Gillespie lived in Seattle for eight months. She hated it. An Army veteran struggling with PTSD, Gillespie suffered from depression and anxiety attacks. She'd spent most of her childhood in Mexico, where she'd grown used to a warmer, more vibrant culture. Combined with the "Seattle Freeze," it was all just too much for her.

“I couldn’t connect with people and I didn’t really give the city a chance — I was just like, 'Oh my God, I can’t live here,” Gillespie says. Eventually, she returned to Mexico.

Two years ago though, she decided to give the city another chance, drawn back by memories of a stint at Joint Base Lewis McCord and a love of the gloomy weather. Through writing, music and photography, she made friends and built community, but freelancing wasn't paying the rent. She needed a way to make a real living for herself.

So, she turned to Google. In central Mexico, she'd spent a few years learning to restore old frames from her then-boyfriend. Maybe, Gillespie thought, she could make money that way. Grabbing her computer, she searched for two words — veteran and restoration.

Fourth on the list of search returns was Vets Restore, a Seattle-based restoration training program for vets.

A laboratory for restoration

A project of 4Culture, Historic Seattle and the King County Veterans Program, Vets Restore trains King County veterans to work in carpentry and historic preservation. Launched last year, the program targets vets who want to work with their hands, but can’t find a job. After seven weeks of unpaid training, participants use what they've learned in a paid six-week apprenticeship program with a local construction firm.

“I do mentoring sessions with the vets and we discuss what the industry is like, what our role in the construction industry is, what benefits are like, what I look for in hiring a carpenter,” says Steve La Vente, a General Build Manager at J.A.S. Design-Build, one of the project's two construction partners. Bear Wood Windows is the other.

The Central District's historic Washington Hall serves as the program's laboratory. Built in 1908 as a fraternal lodge and dance hall, the building was saved from demolition by Historic Seattle, which acquired it in 2009. The building is currently in the third and final phase of a $9.8 million renovation. Vets Restore's first three pilot participants restored the original wood windows of the building in 2013. This year, the program will include five veterans who are continuing the restoration of the wood windows and doors.

Flo Lentz, the project's 4Culture program coordinator, says Washington Hall is the perfect classroom. “It is a big project that will go on slowly for several years,” she explains. “If they were doing a commercial job, they would be pressured with a deadline.”

Originally proposed by 4Culture as a way to introduce new audiences to preservation, the program also helps with the transition back into civilian life. “We are trying to provide a link between military service and civilian life because that transition can be hard,” Lentz explains

It was for Gillespie.

Fighting PTSD

Gillespie is the first to admit she has problems with authority. When she joined the army at 19, her father had just passed away. She told her recruiter to send her anywhere she didn't have to deal with drill sergeants.

"I also wanted to prove to my sister that I was 125 pounds and could make it through basic training," she adds.

That place turned out to be Germany, where she worked in the Army's communications-electronics command, installing, operating and repairing communications systems. After one year, a torn meniscus forced her into office administration while deployed in Iraq. Gillespie also did photography for Army records — taking photos of Iraqi children and other snapshots in the war zone. The attacks she remembers most vividly are the motor attacks. Oftentimes, she would walk around dodging flying pieces of metal hitting the sides of buildings. Those experiences led to her heightened senses and constant anticipation.

"One time, we had 16 attacks in 5 minutes," she says. "You learn to appreciate the little things in life because of that." When she first moved to Seattle, Gillespie was diagnosed with 20 percent PTSD. (Veteran Affairs evaluates PTSD on a sliding scale of 10 to 100 percent.)

A 2010 report found that there are likely more than 20,000 veterans in King County who have experienced PTSD, Traumatic Brain Injury or Military Sexual Trauma. That's about 32 percent of King County's total veteran population. The same report found that the unemployment rate for veterans in King County is 8.4 percent.

Though mental health isn’t at the forefront of Vets Restore's mission, Gillespie says that it has helped her psychologically.

“It is really difficult for a veteran to connect with a civilian because they haven’t been in the situations we have and they don’t understand. People complain about little things and you are just like, ‘Really?’”

Veterans, Gillespie explains, bond over shared experiences. She equates it to a regular civilian meeting someone from their hometown. They might not have known each other, but they can connect about how they know all of the same places.

“You automatically feel at ease,” she says.

Veterans help themselves

Successful graduates of Vets Restore are also self-motivated. “Vets Restore gives you a platter of resources and will help you reshape your resume," Gillespie says, "but it is up to you and what you want to do with everything they give you.”

Only some will graduate with jobs. J.A.S. Design hired one of the program's three graduates last year, but naturally, the bigger the group size, the less chance a participant has of being hired.

“The internship could just be like ‘Okay, see you later!”” Gillespie explains. “They didn’t have to pay a dime because King County is paying our paychecks and these companies are getting free labor and teaching us what they know.”

That last part, about King County financing paid internships, is important. Vets Restore is based on Preservation Through Practice, a program pioneered by the Los Angeles-based Heritage Square Museum, that matched veterans with professionals to work on historic buildings around the city. After a year though, Jessica Rivas, Heritage Square Museum's Director of Administration and Operations, says her team ran up against a lack of funding.

“We could only pull off enough funding for that first year, but we have since received more and are going to try to restart in February,” she says.

Vets Restore is funded by the Veterans and Human Services Levy, which doesn't expire until 2017.

There are many programs around the country that offer veterans help with job training and placement in various fields. However, Lentz says there are fewer than a handful that pair veterans with the preservation trades.

“Returning veterans who are unemployed are looking for a meaningful new mission and working with historic buildings is valuable to the community,” Lentz says. “Connecting veterans with significant historic places is a good way to give them a purpose in life.”

Gillespie, who is in her last few months of Vets Restore, has big ambitions for herself. She wants to find a carpentry business to work for and then attend the Smithsonian's Museum Conservation Institute in Washington D.C. to learn craftsman restoration.

"I'm a big history goof," she says. "I'm just a boring girl who likes philosophy, history and literature, and I'm doing carpentry for a living."