Director Roman Polanski has often preferred to work in enclosed spaces. He discovers madness lurking in hallways, ghosts in bedrooms, menace just outside the frame. The odd guest sometimes arrives, bringing sexual tension or the promise of psychodrama. Maybe the Devil himself will knock at the door.

Polanski's Repulsion featured Catherine Deneuve going quietly insane in her London flat; Knife in the Water, a diabolical threesome on a pleasure boat; The Tenant, a smug newcomer (Polanski himself) in an apartment building convulsed by suicidal paranoia. Even in his more spatially expansive Chinatown and The Pianist, the horrors — incest and extermination — were intensely claustrophobic. It’s no surprise then to see that his latest picture, Venus in Fur, takes place entirely on a theater stage, with two actors engaged in a spirited joust about language, feminism, role-playing and humiliation. The stakes, ultimately, are not very high, but the movie makes for lively and witty entertainment.

Polanski adapts the play by David Ives Broadway without any exterior distractions. A playwright, Tom (Mathieu Almaric) is alone in a theater, frustrated by his inability to find the female lead, the Venus of his drama, which is based on the 1870 novel Venus in Furs by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, the so-called founder of sadomasochism. Tom is about to give up for the night when in walks Vanda (Emmanuelle Seigner), flustered, wet from a sudden rain, late for her audition but desperate to read for the part. Tom relents, and it quickly becomes apparent Vanda is a pro. She relights the stage, nails every line, then begins directing Tom in the male role, even though he never intends to star in his own play.

Thanks to Polanski’s brisk direction, a story that on paper could be as sodden as Vanda’s dress, comes alive. The verbal rococo is often absurdly comic and intellectually pompous, and Almaric and Seigner deliver it with zest. Polanski’s energetic editing and subtle framing makes great use of the small space, and his timing is impeccable. Before we know it, Vanda has turned the tables on Tom, a misogynist who thinks he’s written a brilliant tale of male lust and obsession, but who ends up at the business end of Vanda’s metaphorical whip.

Seigner (Polanksi’s wife of more than 25 years) is a revelation in the part. She is clever, funny and, for a story that hangs entirely on its wordplay, a fierce physical presence. Watching her strut around the stage in black leather and red lipstick, and then later in the skimpier costume of a 19th century dominatrix, is a commanding site. Her Vanda is always ten steps ahead of Tom. The only letdown in the film comes at the end, when she exits too soon, leaving us staring at the writer strapped to a gigantic phallus.

Almaric, too, is in fine nimble form. Nearly a dead ringer for Polanksi in his early years, Almaric starts off as an impatient, self-regarding aesthete and winds up Vanda’s mute and quivering plaything. There is one uncomfortable mention of child-abuse in their interplay, and I wondered if this was Polanski’s nod to his own soiled past, but the characters’ duel of seduction and dominance is really about a rather stale idea of male-female relationships, nothing more.

For that reason, the movie’s final sting contains none of the poison or dread of Polanski’s great films. The heightened theatricality of the setting really hides no secrets, so the space itself says little about what’s going on. Remembering the dread seeping into the tony banality of the Dakota apartments in Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, you can’t help but hope the 80-year old director, with his cinematic eye and uncanny rhythms still on high alert, takes on more unsettling material next time.

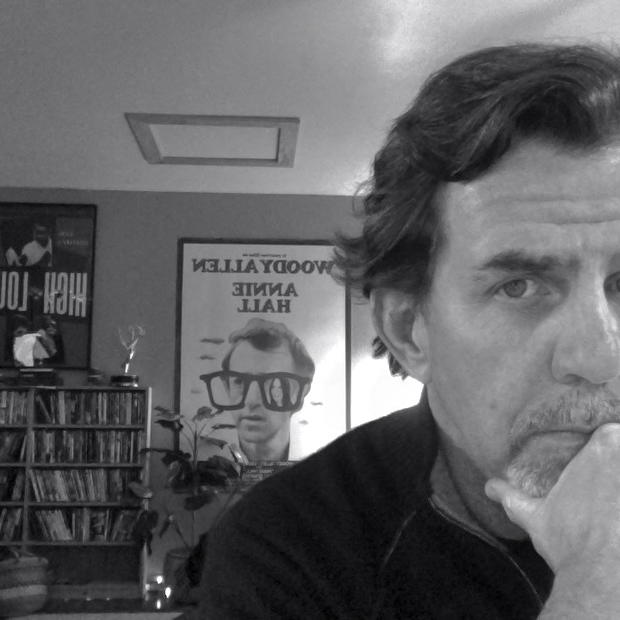

This post originally appear on Rustin Thompson's "The Restless Critic" Blog.