It’s hard to look homelessness in the face. That’s the unintentional message of four short animated films produced by Seattle University’s Film and Family Homelessness Project. The four premiered at SIFF and are now available online.

In the movies, a teenager tells us what it is like to be homeless; a couple is troubled by the idea of buying a foreclosed house; a family reflects on the support they received from the community after falling into homelessness; the voices of fathers are heard as they describe the struggles in providing for their children while not having a place to live.

According to Barry Mitzman, professor of strategic communications and director of Seattle U’s Center for Strategic Communications, the goals of these films are to “increase public awareness and understanding of family homelessness and its causes and solutions, and to engage the public to end family homelessness.” He added that using animation to tell these stories “not only provides a unique perspective on the causes of and solutions to family homelessness, but gives us a different way to outreach to our community and engage them in action.”

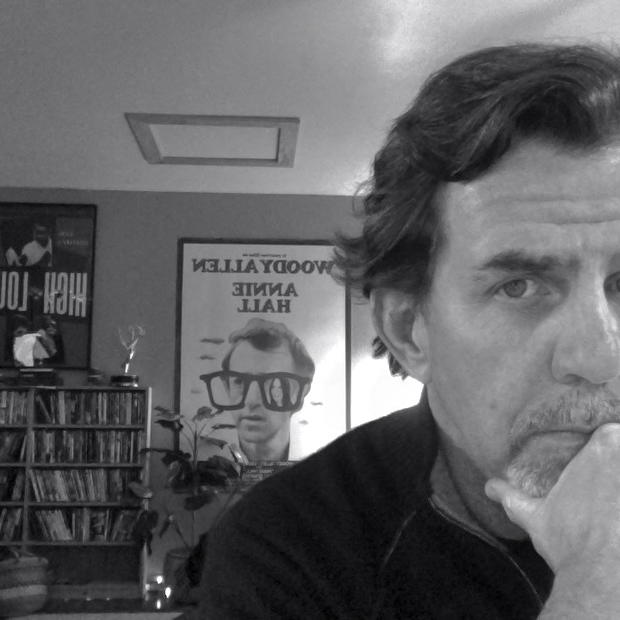

True, animation is a different way to present these real stories of a pressing social issue, but I question how effective the medium is in getting us to confront the realities of homelessness for families, women and children. The films in this package, all of them running about four minutes in length, are only fitfully engaging and often murky in their storytelling. (Full disclosure: This project was an open call to all Washington filmmakers to submit ideas for films. As a filmmaker myself, I was one of 50 who submitted a proposal).

True, animation is a different way to present these real stories of a pressing social issue, but I question how effective the medium is in getting us to confront the realities of homelessness for families, women and children. The films in this package, all of them running about four minutes in length, are only fitfully engaging and often murky in their storytelling. (Full disclosure: This project was an open call to all Washington filmmakers to submit ideas for films. As a filmmaker myself, I was one of 50 who submitted a proposal).

American Refugees is the title of the series, and in the film The Beast Inside, the young man narrating his story expresses his frustration at being a teenager humiliated by homelessness. He certainly sounds like a refugee from normal existence. Directed by Amy Enser and animated by Drew Christie, the film tells his story in a straightforward fashion, with an eye-catching fluidity. But the film ended abruptly, with the young man proclaiming, “things are looking up.” Hard to believe since the evidence appeared grim.

In Superdads, Sihanouk Mariona employed Claymation to portray the daily hurdles of parents trying to ensure food and shelter for their kids. But the short was mostly a confusing tangle of intersecting voices and faceless clay figures that, at times, looked a little freaky. As a documentary filmmaker who has interviewed dozens of homeless men, women and children, the first thing we need to understand is that homeless people look like the rest of us, not like indiscriminate blobs of clay.

Home For Sale was the most coherent of the shorts, with an affecting story of a couple considering the purchase of a recently foreclosed house. As they walk through the rooms, they see and hear the previous occupants dealing with their precarious living situation, culminating in a forced eviction. Director Laura Jean Cronin drew on personal experience for the film, and the movie, while overly simplistic, was clear-eyed and emotionally resonant. However the animation, consisting of layered oil paintings, reminded me of the middlebrow work you’d come across at an art gallery for tourists.

The last of the four, The Smiths, tells a more uplifting story of a how one homeless family was helped by the compassion and charity of another. One imaginative visual passage shows the fingers of a hand dissolving into figures of people representing the supportive community. Neely Goniodsky was the director and animator.

American Refugees is a commendable concept, especially since the stories being told here remind us that the majority of homeless people are often only temporarily undone by dire circumstances beyond their control. Perhaps animation, as opposed to live action documentary or fiction, can reach those audiences who flinch when exposed to too much reality. The technique also, understandably, protects a homeless person’s anonymity. But animation can also act as one more screen between us and the truth.

I wanted to see the actual human faces and hear the real voices of the people whose stories were being told in these films. Stop-motion, Claymation, hand-paintings; these are imaginative, expressive tools, but they are also the end reward. Are we meant here to marvel at the medium or at the message?

To read all Crosscut's Kids@Risk coverage go here.