The Godfather, Manhattan and All The President’s Men. If those were the only three films Gordon Willis ever photographed, he could have gone to his grave happy. That trio of masterpieces defined the golden era of 1970s American cinema, a time when complex characterization, violence, comedy, sex, intrigue, politics and star power were dominant themes in movies, as opposed to the retrograde films of today which are concerned with bottom-lines, tent pole franchises and computer “gee-whizery.”

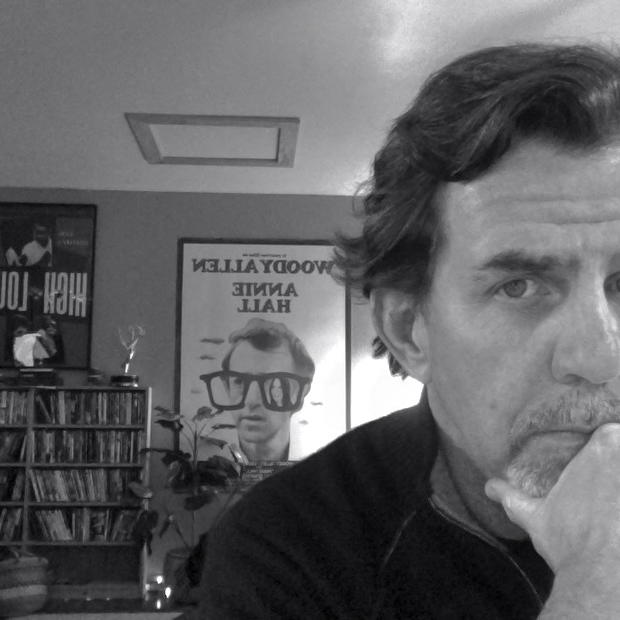

But Willis, who died last week at age 82, didn;t stop there. He was also the director-of-photography on other classic titles such as Annie Hall, Klute and The Godfather II. He lensed 19 movies from 1970 to 1979, and you could argue there wasn’t a lemon in the bunch. I have a personal fondness for his 1972 neo-Western, Bad Company, a naturally lighted picaresque starring the young Jeff Bridges; and The Parallax View, with its assassination atop the Space Needle and Warren Beatty’s near-death by floodwaters, which was shot in the North Cascades.

But it was Willis’s groundbreaking work on The Godfather that earned him the title: "The Prince of Darkness." Studio heads criticized his chiaroscuro lighting of Marlon Brando’s Mafia don, but it was precisely the dark pools in Brando’s eyes and the blurred backgrounds illuminated by lamplight (called "practicals" in the biz) that created the menace and mystery of Vito Corleone and his criminal domain. At the time, films had to be lit for the less-forgiving drive-in movie screen (which is where I first saw The Godfather), but Willis and director Francis Ford Coppola were making an art film which demanded your attention, not a diversion for families and sex-crazed teenagers.

His black-and-white work on Manhattan is most celebrated in the scene-setting tableaus of the Brooklyn Bridge and other iconic landmarks. But for me, the movie’s romantic charm is most affectionately expressed in Willis’ lighting schemes for the interiors: expressive off-whites and grays separated by bands of black, punctuated by the soft glows of candles and desk lamps.

Even more impressive was the dynamic compartmentalization he achieved in All the President’s Men, his breakdown of a scene into boxes of light and dark, the textural density of shadows and silhouettes coming to life, which established “light as character” with a psychological force and real meaning. It was one of three “paranoid thrillers” Willis shot for Alan Pakula, along with The Parallax View and Klute, and to this day all three stand as charged examples of how a film can reflect the mistrust and suspicions of a culture simply by where one places a light. For an in-depth interview with Willis from 2008, go the website Craft Truck.

For more Viral Video nuggets, go here.