Expansive and insightful in its construction, the Frye Art Museum's current exhibits explore the working and cultural relationship of four artists: American sculptor Isamu Noguchi and Chinese calligrapher Qi Baishi, and American sculptor Mark Tobey and Chinese calligrapher Teng Baiye.

Born in Los Angeles to an American mother and Japanese father, Noguchi was primarily a sculptor, a pursuit he honed when, in 1930 at the age of 26, a Guggenheim Fellowship swept him off to Paris to study under Romanian-born sculptor, Constantin Brancusi.

Plans to visit his father in Tokyo afterward were disrupted when his father abruptly disowned him. Noguchi found himself in Peking, the site of the planned trip’s layover. It was there that he met Chinese calligrapher Qi Baishi — a meeting that turned a failed layover into a full six-month residency.

When the two artists met, 68-year-old Baishi was a highly respected calligrapher, chop maker and ink painter. Although Noguchi already saw himself as a sculptor, he spent the next six months in Peking devoted to drawing – the longest such period in his life, and the subject of the exhibition.

Qi Baishi's Crabs, Courtesy Frye Art Museum

Since there are very few extant words written by either artist about their relationship, it is up to Frye visitors to think about those connections. This is fitting, considering that our place – as outsiders to the rarefied world of Chinese ink painting – is parallel to the position of Noguchi in 1930 Peking. He too was an outsider.

There are no outward signs in Baishi’s work of being influenced by the young American. Noguchi, however, was clearly influenced by Baishi. More than anything, he left Peking with an appreciation of the sweep of line that would forever be part of his sculptural practice.

The large paper scrolls on which he worked during his time in China were obviously liberating (and they could be very nicely rolled up and easily and inexpensively taken back to America). As onlookers, we museum visitors get to see him trying out lines on the inviting expanses of paper.

In contrast to Baishi’s mountains and flowers, Noguchi drew from live models, often two figures in counterbalance – two fighters, a mother and child, two nudes. By adopting Baishi’s spare sense of line, Noguchi discovered a new way of depicting figures: Using a thicker ink-filled brush and drawing on top of drawings, giving a fast, dark outline to the figures.

In contrast to Baishi’s mountains and flowers, Noguchi drew from live models, often two figures in counterbalance – two fighters, a mother and child, two nudes. By adopting Baishi’s spare sense of line, Noguchi discovered a new way of depicting figures: Using a thicker ink-filled brush and drawing on top of drawings, giving a fast, dark outline to the figures.

These expressive, suggestive pieces — Mother and Child (at right, Courtesy of the Samuel and Alexandra May Collection), Standing Female, Peking Drawing — give us a strong look at the sculptor following and ‘outlining’ the action in the drawings. In many ways, these pieces are two works in one: a figure drawing and an abstract rendering thereof. Destined to spend many decades (after this Peking interlude) as a sculptor, we can see Noguchi in the early stages of defining planes and pulling a 2-D drawing towards 3-D.

Noguchi’s intention to profit from his time abroad came out of and remains a most American practice. Our artists and intellectuals have long cherry-picked from more ancient cultural practices.

Being of part-Asian parentage, Noguchi was especially intrigued by Asia and what its heritage might mean to and for him. Still, he had no illusions that he would return to the United States as an expert calligrapher.

He came to China as an outsider, and left as one.

Mounted in the Frye's back rooms, as a counterpoint to the Noguchi-Qi exhibit, is the Frye's own curation: A pairing of Mark Tobey and Teng Baiye. Tobey studied calligraphy with the younger Baiye, who came to Seattle to study sculpture at the University of Washington.

Visually this pairing is less effective — primarily because so few Teng paintings exist. Only a couple of the Chinese painter’s works are included in the show, making the visual comparison that works so well in the accompanying exhibit impossible. Intellectually though, their scarcity actually validates the premise of the Frye’s exhibit — that the two artists influenced one another.

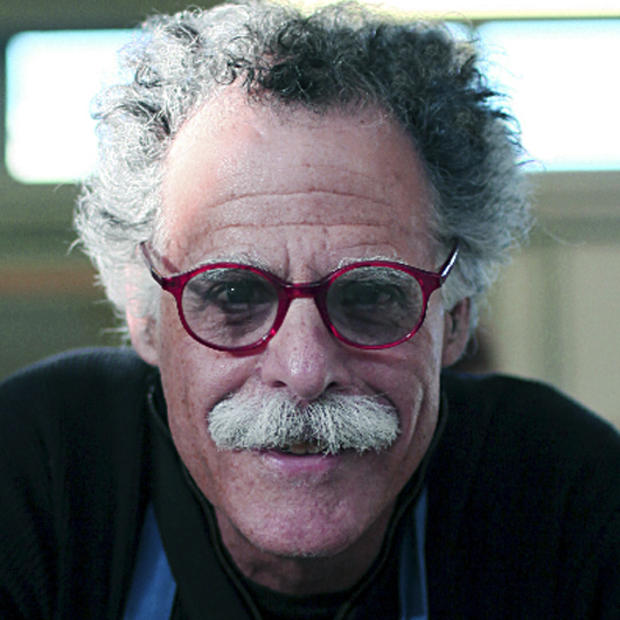

Portrait of Teng Baiye, with dedication to Mark Tobey, 1926. Courtesy, Frye Museum.

Baiye paid a very heavy price for the ‘Western influence’ on his work when he returned to China. He was denounced and sentenced to hard labor for the cross-fertilization that began in Seattle, his paintings destroyed.

We know that Tobey was fascinated by the Far East, and that his keen interest yielded a very personal interpretation.

As with the Noguchi exhibition, the Tobeys, arranged in chronological order, provide us a window into his thinking and process — even if we're not sure how Baiye fits into that process. We see his use of Chinese calligraphy becoming more and more abstract. We see him rendering the calligraphic form that he understands only visually (and not as a system of written communication), into a system of painterly marks.

Like Noguchi before him, Tobey is taking what he needs from the Chinese.

Crosscut's arts coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.