Buster Simpson//Surveyor at the Frye Art Museum through October 13, is a sprawling, compelling and ambitious exhibition. This retrospective is the first for Buster Simpson, and also the first solo artist exhibition at the Frye Art Museum curated by the insightful Scott Lawrimore, who comes to the museum directly from running a respected gallery.

At work in Seattle since the 1970s, Simpson is known far and wide as a leading proponent of art for public places; an important and visionary pioneer in a city that itself pioneered the practice of commissioning artists to situate work in public places. His work in the public realm is often brilliant — far-seeing and understated. It's not surprising that Lawrimore would choose to celebrate his tenure at the Frye by mounting a Simpson retrospective — it’s been long overdue.

Neither is it surprising that it didn’t occur elsewhere earlier. How do you showcase 40-year-old actions and agitprops to an audience, like most Frye visitors, who would likely have paid little attention to Simpson's ideas and installations when they originally occurred?

But Lawrimore wastes no time in tackling Simpson's environmental statement art. Outside the museum, a sidewalk tree is bolstered with the crutches Simpson developed for endangered street trees when he lived and worked in rapidly-changing Belltown. (Other artists who originally worked with Simpson on the crutches — most famously Jack Mackie — remain nameless in the exhibition, like several other of Simpson’s collaborators.)

A tree near the Frye, bolstered by the crutches Simpson and his collaborators developed. Photo: Juju al Daher.

Then, just inside the museum’s portico, we encounter a rough, handsomely pristine piece — a big hunk of tree root swaddled with steel cable to a concrete pier block, sitting gingerly in the museum’s shallow reflecting pool. The museum label says the artist would like to install these as rickrack in coastal areas.

Buster Simpson's coastal rickrack at the Frye Museum. Photo: Juju al Daher.

Right off the bat then we are confronted with the pleasures — and difficulties — of the exhibition. Jim Olson’s highly refined design for the museum greets us with a soothing northwest aesthetic and Simpson gives us another, harkening to our messy tree-growing and lumbering tradition. But though we get the piece in water, it is only a few inches. The tree hunk’s tightly-bound wildness isn’t countered by nature herself, as the artist intended.

Inside the galleries, a judicious mix of media shows us what was and is no longer. We are offered re-creations and re-stagings of objects that Simpson created over the years; glimpses of things outside somewhere, far away; new work done for the exhibition and, at the end, a smidgen of what has been proposed by him for other places.

Chronologically, our tour through Simpson's practice begins with “Selective Disposal Project,” 1973, wherein he and fellow artist Chris Jonic photographed themselves cleaning and salvaging an abandoned loft space. A small, quite lovely, book came out of the exercise, as well as some equally comely pieces framed with mismatched pieces of frames. The label reminds us that collaboration is one of Simpson’s ‘core ideals’.

We also encounter Simpson’s alter-ego Woodman in sheet metal profile. Video (from super-8 footage) shows Simpson as Woodman, once again salvaging — gathering debris from destruction around Belltown.

We also encounter Simpson’s alter-ego Woodman in sheet metal profile. Video (from super-8 footage) shows Simpson as Woodman, once again salvaging — gathering debris from destruction around Belltown.

Lawrimore has lovingly given this early work a great deal of physical and metaphorical space in the exhibition, and lots of supporting text. He understands that all that follows in the artist’s work comes from these initial exploratory interventions.

Moving ahead to 1990, we see a large video projection of Simpson throwing super-sized limestone ‘antacid tablets’ into the headwaters of the Hudson River. This is one of Simpson’s iconic projects — simple in form and intent, resonant in meaning and impact. But to those unfamiliar with its context, the brief repeating tape loop could become, as I overheard it described in the gallery, “a one-liner”.

In the exhibition's last gallery we are surrounded by large, beautiful sculptural pieces created this year. We are left to guess, however, how they came to be made or included in the exhibtion. Despite the grace and the Donald Lipski-like whimsy of the sculptures in the large gallery, Simpson has never been a big producer of stand-alone objects.

In a hallway — the conscripted Graphics Gallery — we get glimpses of Simpson at work in today’s world. Included are a few proposals, as submitted by Simpson, for large public projects. No explanatory or contextualizing information is provided in the show about the proposal documents or the suggestive maquettes also on display. The exhibition's wall text, expansive on the early work, diminishes greatly as we make our way through the galleries. I understand Lawrimore's desire to have the later work speak for itself, but without judicious curator help, it becomes more difficult for the viewer to appreciate the full scope of Simpson's work in the public realm, or its basis in the early 'actions'

It is with these public projects that Simpson has not only made a living, but achieved very well-deserved influence and importance. He is a master at conceiving, making and siting work out in public: Why then is this part of his practice given short shrift?

By foregrounding his objects in the later gallery (as seductive and surprising as they might be), we are treated to some distortion of Buster Simpson as artist. We experience him through what he has made with his hands; less fully through what he has thought, proposed, promulgated or put into play. This seems an old-fashioned view of the artist.

Public art is not Simpson’s day job. It is a logical and righteous extension of his early art actions. His work in public continues to provoke, continues to push at boundaries, but public art is hard to make sexy in a museum setting. Situated outside the crisp white walls, curated neither by museum nor gallery people, it is not cordoned-off or protected from the exigencies of everyday life. It is not, by definition, elitist, nor the rarefied work of a solitary genius. Rather, it comes out of an un-pretty, un-shapely process, long on negotiation and compromise. Almost always it is done with public money and therefore with the involvement of public officials and public opinion.

There are glimpses of this dynamic. The exhibit's introductory text expounds on the importance of Simpson’s oeuvre, its conceptual basis and implicit commentary on development to a city undergoing a wave of dramatic and relentless change.

Simpson is highly skilled at pushing and pulling. We get an early glimpse in a 1974 letter to Seattle City Councilman Bruce Chapman, laying out his provocative (and unheeded) ideas for Myrtle Edwards Park. We see it also in a handwritten note to Diane Shamash, then of the Seattle Arts Commission, trying to secure a deadline extension for his piece in the city’s 1991 celebration of public installations. His proposal for “In Public” was deemed unseemly — it dealt with toilets, so Simpson is buying time to come up with something cleaner. It was Shamash, then as the director of the New York arts organization Minetta Brook, who commissioned Simpson to put the limestone lozenges in the river. Obviously, years later, Shamash still had high regard for Simpson, despite or even because of his toilet talk.

We treasure Simpson as the grinning trouble-maker who inserts himself and his thinking along urban byways. He headed down this path long ago, and though armed now with healthy budgets and a far more practiced and sophisticated approach, he’s still at it. The Frye and its deputy director are to be congratulated for mounting the enticing exhibition. The retrospective is a fine introduction to Simpson’s art practice, though despite the exhibit’s scale, leaves us with only a silhouette of the man at work today.

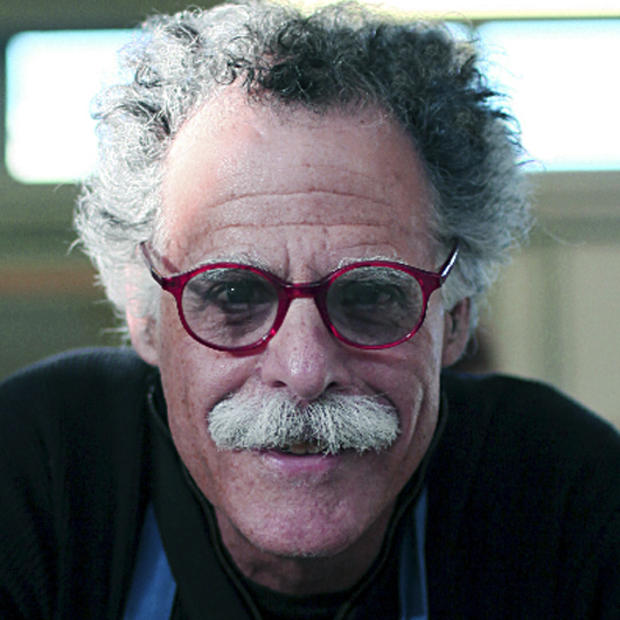

Inset photo: Buster Simpson. Woodman, 1974. Black and white photograph. Courtesy of the artist.