A few weeks ago, as I walked to the Mardi Gras market in the Marigny, a woman came walking my way. She was swaying and sashaying, bedecked in a plethora of alluring colors. As she passed, I realized she was singing softly and beautifully to herself. It was a fine New Orleans morning.

New Orleans is a female city. I awoke at 3 a.m. to that realization, and even in the bright light of day it seemed true. There are of course many male cities; New York immediately comes to mind. I would call Seattle a feminist city, for reasons I'll explain later. But off the top of my head, I can think of no other city in this country which I would describe as female.

NOLA is organized around female pursuits and interests — pleasure, family, food. Having and making sure others have a very good time, easily and regularly comes before the pursuit of profit here. The city and its life are fluid and flowing, defined by a river constantly seeking to overrun itself. Everywhere there are front porches and stoops and everywhere, in wealthy and poor neighborhoods alike, they are in constant use. Of course the weather makes such activity both welcome and necessary — but regardless, the custom here is literally to hang out, in public view, and to wish passersby the best of everything.

Food, beverage, music, and gossip are all happily consumed in full public view, never behind three-foot high fences. There are many "social and pleasure" clubs, peopled by both males and females. Social cohesion, being distinctly female, is the organizing principle behind them. Other cities have such clubs, but they are often bastions of private revelry and retreat. In New Orleans, the clubs fuel the city’s steady stream of public display, in life and in death. The clubs literally strut their stuff in Mardi Gras parades and, at the end of life, second lines and funeral marches. The funerals parades tend to honor male musicians, but they are held for the survivors, most of whom are women.

The day before I left New Orleans, there was a second-line parade for the beloved musician Coco Robicheaux, who had died a couple weeks earlier in his favorite club on Frenchmen Street. Coco was gone, but the assembled musicians blasted their horns for him and his four ex-wives while two wonderfully made-up “drum majorettes” led the way. The loosely organized parade included young and old, black and white, large and slim, the women resplendent in various layers of dress and undress. It is easy to explain the amount of flesh on view in New Orleans by the weather, but while that might be a necessary explanation, it is not a sufficient one. Women in New Orleans seem quite pleased to display themselves to one another and anyone else. It seems this has long been the case. Storied 19th century balls feted the beautiful quadroons, descending from unions between slaves and owners. It’s not that society, white or black, condoned that activity, but it was happy to bask in the beauty of the offspring.

Seattle is a feminist city because so much power here is in the hands of feminists (female and male), people who uphold a strongly liberal and well thought-through code of behavior they hope will deliver equality, well-being, and the fabled dream of progress. It is home to several large corporations and global institutions; NOLA is home to none. This region sells precision in one form or another — in engineering, manufacturing, design, philanthropy, and know-how, even in foodstuffs. We revere technology and tools and consider having and displaying the latest gadgetry of highest importance. This a far cry from the city’s beginnings, when he-men, certainly neither feminists nor precisionists, logged, fished, and trekked off to Alaska in search of gold. Creating global precision is still very much a male pursuit, even if many of the executives who run the operations that produce it are feminists. The primacy of technology has come to seem a given here.

New Orleans was once the country’s third-largest city, and became so based on trade, the basic exchange of goods. Exchange depends on relationships, and relationships have always been the purview of women - even when it is men who do the actual trading. New Orleans has seen multiple waves of immigrants in its three centuries of existence; they came because of hardship or revolution in their home countries, stayed because they could make a living off the waterborne trade and its ancillary employments and were charmed by the city’s unique feminine allures. Their numbers included free blacks fleeing troubles in Haiti. Slavery of course brought many others, but even slaves could get together on Sundays to eat, gossip and make music. These Sunday get-togethers in Congo Square are credited with the birth of jazz.

New Orleans now has less than three-quarters the population it did before Katrina; it’s estimated that a third of the African-Americans living in the city before the disaster have not returned. This black leave-taking is a terrible loss to the city and of its heralded culture. The blacks have long nurtured the city’s unique cultural traditions, assuring their passage from generation to generation.

The latest immigrants to the city are young college-educated whites. They bring with them an appreciation of and appetite for New Orleans’ music, food, and general way of being, as well as some skillsets not in large supply there. It remains an open question how this exchange, of mostly poor and poorly educated blacks for generally better funded and distinctly better educated whites will play out there. Will the new immigrants remain, will they be molded by the female sway of the place, or will their presence tilt it toward something more Seattle-like?

In NOLA social interaction is renewed daily, played out in small and grand ways. Folks ask strangers and others many times a day how they are doing. Smiles and nods are offered freely and often. It is not assumed that such behavior will make anyone better off, economically, socially, or physically. Eating lots of fried food is clearly a bad idea, as is drinking all day - but they are accepted because they make people feel good. A freshly made oyster poor-boy is sublime. People in Seattle walk down the street carrying coffee in plastic cups. In New Orleans the cups usually hold beer or daiquiris.

Many people, mostly younger as in Seattle, ride bikes in New Orleans. It’s a totally flat city, making pedaling a pleasure. But that doesn’t explain why almost none of the riders swath their rear ends in Spandex. (There’s plenty of Spandex worn in NOLA, but it’s for straight-out display, not technical function.) Musicians carry their instruments strapped to themselves or to trailers connected to their bikes. And many young women ride in beguilingly fitting clothes- full skirts, miniskirts, intersecting layers, bodices, whatever. Often they look dressed to kill. In Seattle, the bicyclists who nearly run me over on Capitol Hill seem dressed to kill in a more literal sense, like characters in a superhero comic.

New Orleans is a fecund place, hot and humid. Trees lift up sidewalks, vines grow in and out everywhere. And the holes and buckled concrete stay there. In Seattle, until recently, there were funds to fix such things as rippling sidewalks. New Orleans takes more of a live-and-let-live attitude – to people, flora, fauna, and broken concrete. NOLA is not an OSHA-approved place, but people don't seem to trip any more in New Orleans than in Seattle. And they walk much more. They learn to watch where they walk.

NOLA's streets run in a regular grid, as do Seattle's. But they have names, not numbers - melodious and evocative names, a street-signed panorama of history, whimsy, theater, music, and art. The signs invoke the muses, the Greeks, pirates, gods and goddesses, heroes and villains. The nomenclature is part and parcel of the community it serves, not just a tool for way-finding.

When I taught young kids, I noticed that the mothers who seemed most comfortable with being mothers helped their kids learn to watch out for themselves. Those who thought it was the teacher’s or society's job to protect their children seemed to actually put them at more risk. In this female city, you learn from a young age to take care of yourself and one another. That’s the women’s way.

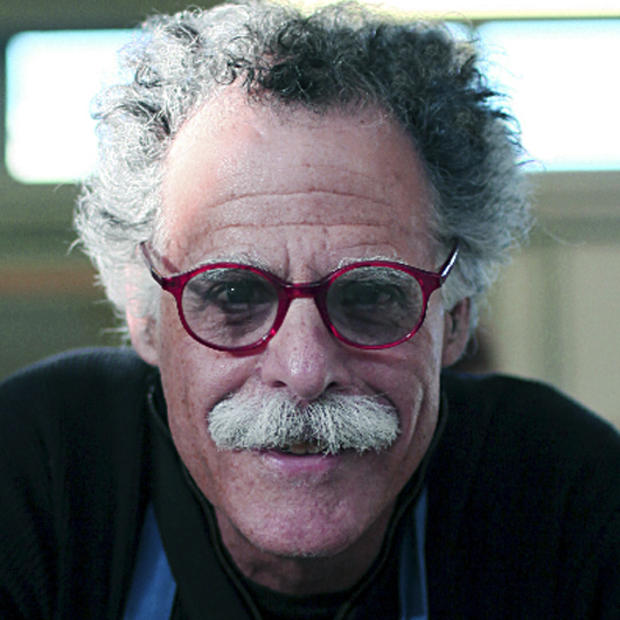

I talked with a thoughtful white artist who lives simply in a small shotgun house with his young family in a predominantly black neighborhood. They are active in the neighborhood church and committed to the neighborhood as it is- they want their kids to grow up in a mixed-race environment, their community to reflect diverse views. They want to share with and learn from their neighbors. In short they don’t want the neighborhood gentrified.

The local elementary school, like much else nearby, was totaled by Katrina; it's now being completely rebuilt. Part of the considerable expense is going to create ‘smart’ classrooms with Internet connectivity, etc. But already there's a projected shortage of teachers at the school, and more funds are needed to complete the building, which is nowhere near ready to open. The well-educated young artist said he couldn’t care less if there were smart boards in his kid’s classrooms - he wanted a full, well-supported complement of good teachers.

In Seattle one might not hear the situation presented in the same way. Seattleites, long ago convinced of the efficacy and raw importance of technology, but still knowing that good teaching matters, would want both. But today that is becoming an impossible combination almost everywhere. The female point of view (and elementary schools remain predominantly the realm of mothers and other women), would strongly favor the teachers, and support a connectivity of a much more basic type. If the newest NOLA immigrants can defend their newly adopted neighborhoods, the city has a chance of both retaining its female character and moving into the 21st century. If the bureaucracy prevails, it’s apt to bequeath a messy, imprecise version of precision.

The women in New Orleans’ African-American society are especially strong. Often they raise their children alone, and later their grandchildren. They are the community organizers, regular churchgoers, ubiquitous entrepreneurs. But even they cannot stem the tide of criminality that flows like water through breeched levees and sweeps up their young men. Without a strong contingent of males to serve as role models, young men succumb to the lure of easy money, and kill each other for the spoils.

This is not the place to enumerate all the indignities the black community has faced, especially since the massive white flight that followed court-ordered integration in the 1960s. The bottom line is that there has been no bottom line in New Orleans for many decades. Like the saturated soil, the line keeps sinking. The whites fled out of fear, leaving the blacks a city with an ever-declining tax base and a self-fulfilling prophecy of decline. Even strong women cannot make schools teach, hospitals cure, police intervene, when there are no funds to pay for the services. NOLA is a female city, but it badly needs strong males.

It would be stupid and pointless to argue that the Crescent City is a better or worse place than the Emerald City. They stand as extremes on a philosophical continuum. Mastering all knowledge, in Seattle , and experiencing everything, in New Orleans, both represent impossible dreams. Somewhere between might be a model to strive for.

Don Fels, a visual artist and Seattle area resident, recently spent a month in New Orleans completing an installation for Prospect, the city’s biennial, with his wife, architect Patricia Tusa Fels. Their House/Atlas is on view there through Jan. 29.