Seattle'ês popular spring garden show, all but thrown on the compost heap for lack of new financial support, may bloom again. Duane Kelly, the show'ês impresario, who'ês calling it quits after 21 years, tells Crosscut he'ês had several inquiries from prospective buyers. Some for the Seattle show, which closed its five-day run at the Convention Center January 22. Others are asking about the upcoming similar flower show in San Francisco that Kelly has operated since 1997.

'êThree or four parties in each market appear quite interested,'ê Kelly says. The inquiries are coming from private parties 'êwith a passion for gardening'ê and also from nonprofit horticultural and nursery trade groups, he says.

Staging a large annual trade show with a million-dollar budget might seem a stretch for a nonprofit, even one staffed by garden enthusiasts. Not necessarily. The nonprofit Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, has run the Philadelphia Flower Show, which bills itself as the world'ês largest indoor garden exposition, for 180 years. (That's not a misprint. The Philadelphia show began in 1829.)

Seattle and San Francisco are the second and third largest garden shows in the U.S., after Philadelphia.

Attendance at the Seattle event, formally known as the Northwest Flower & Garden Show, has been in slow decline in recent years. This year, however, attendance was up 3 percent from a year earlier to 54,443. A 'êlast hurrah'ê factor — gardeners lured by the belief that the show really was closing for good — may have been at work.

But Kelly says a marketing campaign aimed at luring a younger audience also helped boost the gate. There were e-mail blasts directed at young people and a larger share of the 110 seminars and workshops at the show were aimed at novice gardeners. 'êOur research showed younger people were intimidated by the old show,'ê Kelly says. 'êThey thought it was too sophisticated. But the beginning gardener today is a serious gardener tomorrow so we changed the content.'ê

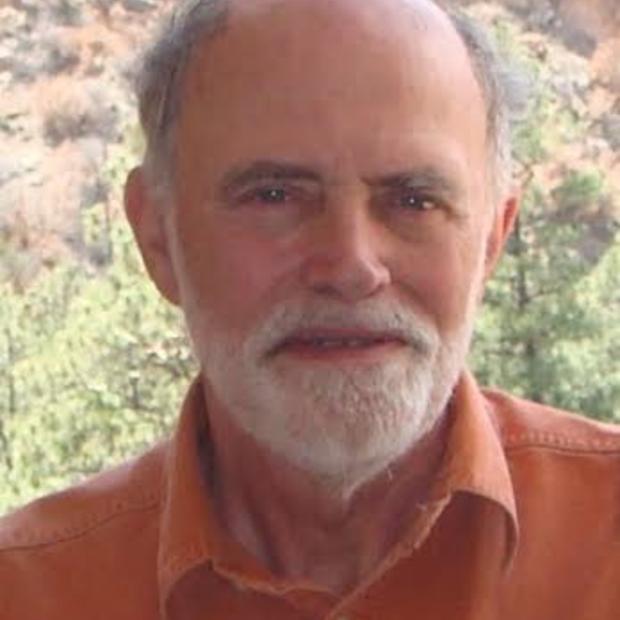

Kelly, 59 years old, admits the recession has taken a toll. 'êI'êve struggled this past year since some of our national sponsors didn'êt renew their contracts.'ê One example: Azusa, Calif.-based Monrovia, the world'ês largest grower of container plants for the nursery trade, sharply cut back its presence and its financial backing.

So what's to entice a buyer to step up when the economy's in the dumps? Kelly says with the boom in all things green, younger people will take to gardening in a big way, ensuring a new generation of show attendees. The garden industry is also more recession-proof than most, he adds. As for Seattle, the flower show was the convention center's first event when it opened in 1989.

"We're part of the cultural landscape of the Pacific Northwest," he says. The show's annual appearance in chilly mid-February is a sort of semi-official kickoff to spring. "We moved the garden season ahead two months for the nursery and landscape industry. I'm proud of that." The show also pumped $6.6 million in sales into the Northwest economy last year.

Kelly promotes the two events, with an annual budget of $3.3 million, under the umbrella of his company, Salmon Bay Events, based in Ballard. He has eight full-time employees and he says all will be laid off at the end of March unless he has a firm purchase commitment. 'êIt would break my heart but I'êm prepared for that,'ê he says.